ESN is currently creating a Faith/Science curriculum for young adult small groups. We've partnered with InterVarsity graduate student discussion groups to identify faith/science questions that are important to emerging scholars, and we're commissioning thoughtful Christians in science or theology/philosophy/history of science to explore those questions in this series at the ESN blog. We will then publish these posts as a booklet curriculum for campus groups. You can find previous posts in the series and related posts … [Read more...] about How Can the History of Science Encourage the Church? Part 3: Modern Christianity (STEAM Grant Series)

History of Science

How Can the History of Science Encourage the Church? Part 2: Medieval Christianity (STEAM Grant Series)

ESN is currently creating a Faith/Science curriculum for young adult small groups. We've partnered with InterVarsity graduate student discussion groups to identify faith/science questions that are important to emerging scholars, and we're commissioning thoughtful Christians in science or theology/philosophy/history of science to explore those questions in this series at the ESN blog. We will then publish these posts as a booklet curriculum for campus groups. You can find previous posts in the series and related posts … [Read more...] about How Can the History of Science Encourage the Church? Part 2: Medieval Christianity (STEAM Grant Series)

How Can the History of Science Encourage the Church? Part I (STEAM Grant Series)

ESN is currently creating a Faith/Science curriculum for young adult small groups. We've partnered with InterVarsity graduate student discussion groups to identify faith/science questions that are important to emerging scholars, and we're commissioning thoughtful Christians in science or theology/philosophy/history of science to explore those questions in this series at the ESN blog. We will then publish these posts as a booklet curriculum for campus groups. You can find previous posts in the series and related posts … [Read more...] about How Can the History of Science Encourage the Church? Part I (STEAM Grant Series)

Science Corner: Looking Back to Move Forward

Happy New Year! As folks transition back to campus and work and other normal routines from the holidays, I thought it would be a good time to take stock and lay out a plan for the coming months of science blog posts. There will still be posts about new developments in science, particularly as they pertain to faith questions or religious concerns. As I mentioned last week, we'll try another round of the blog book club; I'm hoping to start that on February 7th. I also want to try some new kinds of posts as I continue to … [Read more...] about Science Corner: Looking Back to Move Forward

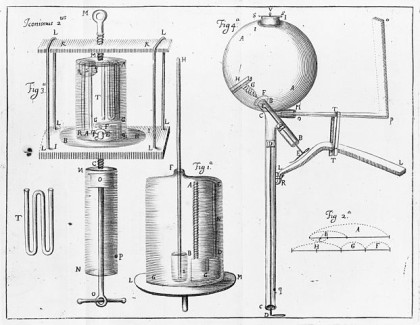

Finding Common Ground: Christians, Scientists, and History of Science

Dr. Josh Swamidass will be speaking about faith and science at several upcoming Veritas Forums. The first is this coming Monday, February 22, at the University of Montana. If you're in the area, check out details here. Here at ESN, we'll be running a short tie in series exploring aspects of faith/science interaction related to Josh's talks. This will be the first of a few posts, including several from Dr. Swamidass, and perhaps a piece or two from some of ESN's other thoughtful science writers as well. It … [Read more...] about Finding Common Ground: Christians, Scientists, and History of Science