Last week, I discussed what happens after a herd immunity threshold is reached, an aspect I had not seen widely talked about. Continuing in that vein, let’s talk about COVID-19 boosters. Vaccines are valuable both as personal medical interventions and as public health interventions. Those roles overlap, but not completely. Articles like this one do a good job discussing the evidence for why boosters are being considered, and framing their value from a personal medical perspective. However, my sense is that the biggest benefits from boosters specifically pertain more to their public health value, and I don’t think that is coming across as clearly.

So what’s the difference between a personal medical intervention and a public health one? Obviously anything that improves the health of an individual also improves public health. When a vaccine prevents the recipient from becoming ill, that’s a personal medical intervention that also provides public health benefit. Other drugs and surgeries contribute similarly. At the same time, there can be public health benefits distinct from the improved health of the person receiving the vaccine. When the vaccine also prevents that person from infecting others, regardless of their vaccination status, that’s an additional public health benefit. And the evidence thus far makes me think the biggest impact of widespread boosters will come via this public health benefit.

To understand why I think boosters will be more about protecting others than the recipient, let’s talk a little about long-term immunity. We’ve talked before about the adaptive/evolutionary process by which you body learns how to make antibodies that closely match a virus. The end results of this process are B cells whose genomes have been uniquely modified to make those very specific antiviral antibodies, plus supporting T cells, plus a whole bunch of those antibodies circulating in your bloodstream and present in your nasal passages and other sites of potential infection. The antibodies can actually block the viral particles from getting into your cells in the first place, which makes them an important frontline defense for your immune system. The B cells can make more antibodies, and the T cells can help the B cells and can also prevent already-infected cells from making more virus, but both of those interventions are slower than antibodies.

That’s the situation right after vaccination or infection. Making lots of antibodies is somewhat expensive, however, plus they might not work as well if your body always had lots of every antibody it knew how to make floating around all the time. So, in the weeks and months after exposure, your body ramps down antibody production and breaks down the ones it made so there is less circulating. This happens with all infections and vaccines. Your body still hangs on to the B cells and T cells that can target that virus specifically. Should you get exposed again, your body will ramp production back up, skipping the time-consuming evolutionary step and going straight to the memory bank for the solution it already learned. Typically, that response is still quick enough and robust enough to prevent the virus from replicating too much and making you seriously ill. However, it’s not quite as fast as if the antibodies were already around, and so sometimes your body might make some virus, perhaps enough to spread to others and possibly even make you temporarily ill.

If you’d like an analogy, I’ve seen lots of cartoons imagining the vaccine as like a wanted poster. Out of respect for the active discussions about appropriate policing, let’s tweak that a little bit to a missing dog poster. When a dog goes missing, the owner might make many posters and hang them all over their community so that the image of the dog will be fresh in the minds of anyone who comes across their pet. After the dog is found, the owner no longer puts up posters, but maybe they don’t go around and take them all down either. Over time, the posters might be covered or damaged by weather or removed, and eventually they won’t be around. But the owner keeps the original poster document, so they don’t have to go through the process of making it again, they can just print more copies. Similarly, your body doesn’t keep antibodies around forever, but keeps what it needs to make them.

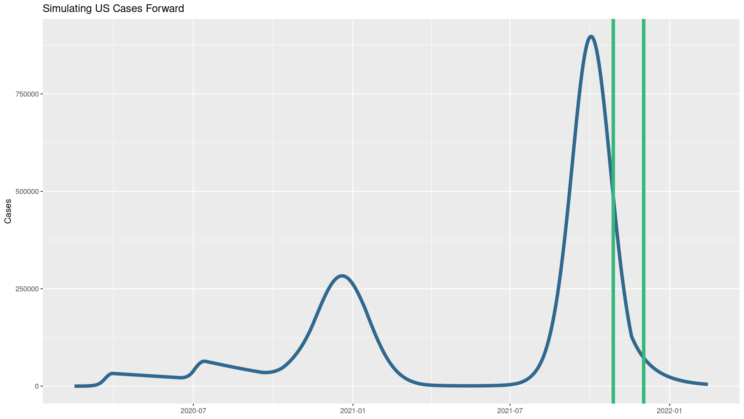

This is long-established immunology, and the evidence from COVID-19 thus far is consistent with this timeline of immunity. Antibody levels drop over a span of months following vaccination (or infection), and after that time there is some increased susceptibility to infection and mild illness but still very effective protection from serious illness and hopsitalization. From a medical perspective and in terms of the collective health of the vaccinated, there’s not much difference between high and low circulating antibody scenarios. From an overall public health perspective, however, there may be a big difference. In the high circulating antibody scenario right after vaccination, the antibodies deal with viral particles immediately and very few vaccinated people make enough virus to infect anyone else. In the low circulating antibody scenario months later, however, more of those vaccinated people will be able to spread to others while their bodies ramp up antibody production again, leading to greater transmission. That puts more unvaccinated people (including young children for the near future) at risk. Booster shots would likely get that antibody production ramped up, cutting down on transmission, protecting the unvaccinated, and also preventing some amount of mild illness as well which can be unwanted even if it won’t put you in the hospital. Plus there are the secondary benefits of preserving hospital capacity and the mental well-being of our healthcare workers, and reducing the possibility of further mutations.

To some degree, that puts booster shots closer to benefit profile of masks–mine protects you, yours protects me–than the initial round of vaccination was, but that can still make them worthwhile. I think that full picture of the rationale also explains better why we are considering boosters when so much of the world still has not received first doses. We have a responsibility as a nation to keep our outbreak under control so we are not breeding further variants of concern or just generally serving as a reservoir to infect other countries, in addition to our responsibility to help everyone else get vaccinated. I definitely see room for prioritizing those responsibilities differently, and ideally we would manufacture enough vaccine to fulfill both. Mostly I just want to help make sure we have the full picture available for the necessary conversations.

Andy has worn many hats in his life. He knows this is a dreadfully clichéd notion, but since it is also literally true he uses it anyway. Among his current metaphorical hats: husband of one wife, father of two teenagers, reader of science fiction and science fact, enthusiast of contemporary symphonic music, and chief science officer. Previous metaphorical hats include: comp bio postdoc, molecular biology grad student, InterVarsity chapter president (that one came with a literal hat), music store clerk, house painter, and mosquito trapper. Among his more unique literal hats: British bobby, captain’s hats (of varying levels of authenticity) of several specific vessels, a deerstalker from 221B Baker St, and a railroad engineer’s cap. His monthly Science in Review is drawn from his weekly Science Corner posts — Wednesdays, 8am (Eastern) on the Emerging Scholars Network Blog. His book Faith across the Multiverse is available from Hendrickson.

Leave a Reply