Introduction

In previous blogs, we’ve seen that God reveals himself to man through nature and through scripture and we’ve been addressing questions about how man’s interpretations of these revelations can be reconciled. In the next two blogs we are going to address a different question: can nature be used as a Christian apologetic? In other words can Christians use nature in some way for evangelism?

The heavens declare the glory of God;

the skies proclaim the work of his hands.

Day after day they pour forth speech;

night after night they reveal knowledge. — Psalm 19:1-2For since the creation of the world God’s invisible qualities—his eternal power and divine nature—have been clearly seen, being understood from what has been made, so that people are without excuse. — Romans 1:20

These verses imply that something about God can be known from nature. Romans 1:20 further suggests that there is moral accountability for what is revealed in nature. Natural theology is a discipline that systematically explores a proposed link between God and nature. The traditional approach to natural theology sought to “prove” God’s existence from what is observed in nature without reference to the Bible or other sacred documents. William Alston, a Christian philosopher, defined natural theology as

the enterprise of providing support for religious beliefs by starting from premises that neither are nor pre-suppose any religious beliefs.

Problems with the traditional approach to natural theology

There are two problems with the traditional approach. First nature is ambiguous with respect to the question of God. In a previous blog post (i.e., Does science rule out God?) we found that the argument from Richard Dawkins and other atheist scientists that science rules out God is a worldview interpretation rather than a necessary conclusion from science. This is because reality is complex and multi-leveled. While science is the best tool for studying nature, its competence does not extend to the other levels (aesthetic, moral or spiritual). Thus one cannot rule out God through science (nature) alone.

We also looked at the Intelligent Design argument for the existence and action of God in creation (i.e., Does Intelligent Design Rule Out Evolution?). This is a classic example of the traditional approach to natural theology which seeks to find evidence for God’s activity within gaps in the chain of natural explanations. The problem here is that these gaps could be due to God or some as yet unknown natural mechanism. William Dembski developed a design filter to distinguish between these two possibilities, but it works through the process of elimination and one can never be sure that all of the natural possibilities have been eliminated. This significantly weakens the argument from design.

The second problem with the traditional natural theology approach is that even if the approach were successful it doesn’t lead to the Christian God, the God of the Bible. In fact in the case of the intelligent design argument it doesn’t necessarily lead to God at all. All that it purports to show is that there is an intelligent designer who could for all we know be a super intelligent alien civilization.

In this post I’m going to discuss a book by Alister McGrath called The Open Secret: A New Vision for Natural Theology. This book develops a distinctly Christian approach to natural theology that overcomes the problems mentioned above with the traditional approach. McGrath argues that nature must be “read” or “seen” in certain ways in order to disclose God. He views Christian theology as a framework or worldview that allows nature to be seen in a way that it discloses God.

What is a metaphysical framework (or worldview)?

Before we look more closely at McGrath’s ideas we need to define what we mean by a worldview. In his book, The Universe Next Door: A Basic Worldview Catalog, James W. Sire defines a worldview as framework that provides the foundation on which we live and move and have our being. It is a commitment that involves the mind but is primarily a fundamental orientation of the heart. It can be expressed as a story or a set of presuppositions that we hold. Everyone has a worldview whether they explicitly recognize it or not.

John Polkinghorne, in his essay Theology in the University sees a secondary role for theology as a framework or worldview that organizes the different facets of the human experience (i.e. nature, beauty, morality and theology in its primary role). It is the big picture which provides a model or mental map that incorporates and explains all the other facets of human experience. Note: For more visit the earlier post Does science rule out God?

A worldview answers the big questions of life:

- Origin – where did I come from? Do I have intrinsic value? If so, what is the source of that value?

- Meaning – what is the purpose of my life? How does my life fit into the larger worldview story?

- Morality – how should I live? Is there some absolute standard for my behavior? Is there such a thing as right and wrong?

- Destiny – finally what happens when I die? Is there any hope for a future after death? What would that be like?

A question of discernment

The problem of the ambiguity of nature with respect to the question of God boils down to one of discernment. This is the difference between observing something and understanding it, between looking at something and really seeing it.

Alister McGrath uses the example of a human condition called visual agnosia to illustrate the issue of discernment. The condition is caused by damage to the cerebral cortex in the vicinity of the temporal lobes which are connected to the visual cortex. Individuals can see objects, but they can’t identify them. The problem is one of linking visual information with stored knowledge about the meaning of that information. For example a person with visual agnosia may see an apple as something that is round with a smooth, shiny surface. It is green, hard and has a brown stem. But that person will not be able to identify what it really is. For example the person may wonder if it is used for combing your hair? What happens is that visual information is transmitted to the visual cortex but the cortex is unable to process the information properly in order to figure out the meaning of the information. A person with visual agnosia can see the parts but can’t understand the object as a whole.

McGrath sees this condition as a metaphor for the human perception of nature. We can see the constituent parts, yet we fail to understand the meaning of the whole. Without additional information we can’t see big picture. In other words we can’t see how all of the component parts fit together to form a whole.

The Parable of the Sower

McGrath uses the example of Jesus’ parables to illustrate the need for a key to understand the deeper meaning of nature. The imagery of the parables is readily grasped but the deeper meaning is hidden. Appeal to the familiar doesn’t automatically lead to deeper truths.

A particularly good example of this is the parable of the sower:

A farmer went out to sow his seed. As he was scattering the seed, some fell along the path, and the birds came and ate it up. Some fell on rocky places, where it did not have much soil. It sprang up quickly, because the soil was shallow. But when the sun came up, the plants were scorched, and they withered because they had no root. Other seed fell among thorns, which grew up and choked the plants. Still other seed fell on good soil, where it produced a crop—a hundred, sixty or thirty times what was sown. Whoever has ears, let them hear. — Matthew 13:3-9

Imagine that you were standing in the crowd listening to Jesus. What would have been your reaction? Remember that this was an agrarian culture so you would have been very familiar with agriculture practices and in particular how to plant seeds. Your first response might have been, Huh? I already knew that. But, you would also know that Jesus was a wise teacher, “the crowds were amazed at his teaching, because he taught as one who had authority, and not as their teachers of the law” (Matthew 7:28-29). This would suggest that there must be more to the teaching than you could understand. The last sentence in this passage “Whoever has ears, let them hear.” would also suggest that.

Later when he was alone with his disciples, they asked him to explain the meaning of the parable. This is what Jesus said,

Listen then to what the parable of the sower means: When anyone hears the message about the kingdom and does not understand it, the evil one comes and snatches away what was sown in their heart. This is the seed sown along the path. The seed falling on rocky ground refers to someone who hears the word and at once receives it with joy. But since they have no root, they last only a short time. When trouble or persecution comes because of the word, they quickly fall away. The seed falling among the thorns refers to someone who hears the word, but the worries of this life and the deceitfulness of wealth choke the word, making it unfruitful. But the seed falling on good soil refers to someone who hears the word and understands it. This is the one who produces a crop, yielding a hundred, sixty or thirty times what was sown.” — Matthew 13:18-23

The key to understanding the meaning of this parable is to see that the seed represents the word of God and that the soils represent different heart conditions of those who hear the word.

The Christian framework as the key to understanding the deeper meaning of nature.

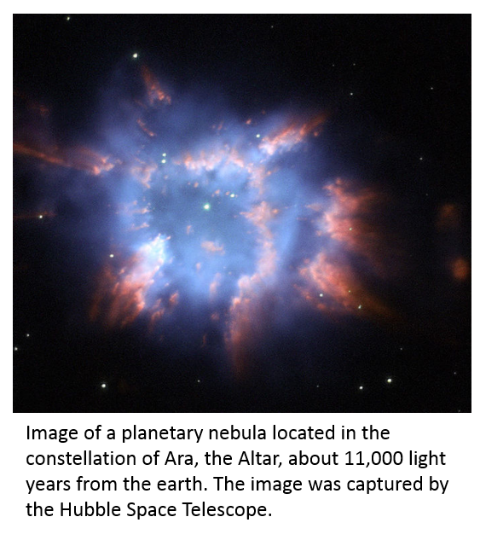

The awe of creation. Go outside on a clear night, if you are like me you will experience a sense of awe and wonder at the vast number and beauty of the stars in the sky. As a young man King David surely experienced this sense of awe when as a shepherd he viewed the night sky. It is his reflection on this experience that gave rise to Psalm 19. But, the universe is unimaginably larger than David was able to observe with his naked eye. At most he could see a few thousand stars. Science has revealed that there are on the order of 100 billion stars in our galaxy (the Milky Way) and that our galaxy is but one of 100 billion galaxies. If you do the multiplication that is 1 x 1022 stars or another way of expressing that number is 1 followed by 22 zeros! The universe is also even more beautiful than David imagined (for example see the Hubble Space Telescope image of a planetary nebula).

The awe of creation. Go outside on a clear night, if you are like me you will experience a sense of awe and wonder at the vast number and beauty of the stars in the sky. As a young man King David surely experienced this sense of awe when as a shepherd he viewed the night sky. It is his reflection on this experience that gave rise to Psalm 19. But, the universe is unimaginably larger than David was able to observe with his naked eye. At most he could see a few thousand stars. Science has revealed that there are on the order of 100 billion stars in our galaxy (the Milky Way) and that our galaxy is but one of 100 billion galaxies. If you do the multiplication that is 1 x 1022 stars or another way of expressing that number is 1 followed by 22 zeros! The universe is also even more beautiful than David imagined (for example see the Hubble Space Telescope image of a planetary nebula).

But just as in the parable of the sower, nature has a deeper meaning that goes beyond the mere scientific facts. God’s word raises the curtain on the mystery of nature. The stars and the universe are God’s creation! As I discussed previously that is the main message of Genesis 1. As Psalm 33:6-9 declares:

By the word of the LORD the heavens were made,

their starry host by the breath of his mouth.

He gathers the waters of the sea into jars;

he puts the deep into storehouses.

Let all the earth fear the LORD;

let all the people of the world revere him.

For he spoke, and it came to be;

he commanded, and it stood firm.

A purely naturalistic understanding of nature is thus an impoverished view. Science can describe what happened after the universe came into existence but doesn’t explain how or why it came into existence. Science doesn’t tell us that the universe points to something greater than itself – the glory of the God who created it (see Psalm 19:1-2).

A question of significance. Copernicus showed that the earth is not the center of the universe. Since then science has revealed that our sun is just an ordinary star among a vast number of stars in the universe. It does not occupy a special place in the cosmos. Moreover the earth is just an ordinary planet located in an ordinary solar system. This is known as the principle of mediocrity or the Copernican Principle. This raises questions about the significance of humankind and of our planet earth.

In his book, Pale Blue Dot: A Vision of the Human Future in Space, the late Carl Sagan reflected on the meaning of a photograph of the earth taken by the Voyager 1 space probe from a distance of 3.7 billion miles. The earth appeared as a tiny bluish-white dot within the darkness of deep space. Sagan stated:

The earth is a very small stage in a vast cosmic arena. . . . Our posturing’s, our imagined self-importance, the delusion that we have some privilege position in the universe, are challenged by this point of pale light. Our planet is a lonely speck in the great enveloping cosmic dark.

Interestingly enough, King David asked this same question (three thousand years ago) in Psalm 8:3-4:

When I consider your heavens,

the work of your fingers,

the moon and the stars,

which you have set in place,

what is mankind that you are mindful of them,

human beings that you care for them?

But he had a very different answer from that of Carl Sagan, in verses 5-6 of Psalm 8 King David writes:

You have made them a little lower than the angels

and crowned them with glory and honor.

You made them rulers over the works of your hands;

you put everything under their feet . . .

Once again the Christian framework reveals a deeper meaning that stands in marked contrast to the bleak view expressed by Carl Sagan. The significance of mankind is not based on size or location in the universe but rather on the fact that humans are created in God’s image with a purpose. Because God is our creator, mankind reflects God’s glory and honor. Again this is one of the main themes of Genesis 1 and it is echoed over and over again throughout the Bible.

Conclusions

In this blog post we have looked at two approaches to the use of nature as an apologetic for God (natural theology). The traditional approach which dates from the “Age of Reason” seeks to prove the existence of God from nature alone without any reference to God’s revelation in nature. This approach was seen to be problematic because of the ambiguity of nature with respect to the question of God.

The second approach, proposed by Alister McGrath, views nature as an “open secret” that is publically accessible but whose true meaning can only be known from the perspective of Christian faith. This Christian natural theology does not attempt to prove the existence of God from nature but rather sees what is observed in nature as reinforcing an existing belief in God. The apologetics of this approach is grounded in the resonance or complementarity between the Christian worldview and what is observed in the natural world. McGrath argues that Christianity offers the best explanation of a complex and multifaceted reality. As C. S. Lewis put it

I believe in Christianity as I believe that the Sun has risen – not only because I see it, but because by it, I see everything else. — Is Theology Poetry?

Looking Ahead. In my next post we are going to continue looking at nature as a Christian apologetic by revisiting the Intelligent Design argument from McGrath’s perspective of a Christian natural theology.

Questions for Further Reflection:

- How do you answer the four worldview questions: Origins, meaning, morality and destiny?

- What do you think about McGrath’s proposal for a distinctively Christian approach to natural theology compared with the traditional approach?

Suggestions for Further Reading:

- The Open Secret: A New Vision for Natural Theology, Alister E. McGrath. Wiley-Blackwell, 2008.

- The Universe Next Door: A Basic Worldview Catalog, 5th edition. James W. Sire. InterVarsity Press, 2009

- Theology in the University in Faith, Science and Understanding, John Polkinghorne. Yale University Press, 2001.

- Is Theology Poetry? in The Weight of Glory, C. S. Lewis.

- Added by the editor: PDF with the titles and links to the posts in Tom Ingebritsen‘s Christianity and Science series. Yes, this was created to meet the requests of readers and will be updated. Your interest in and encouragement of this series is much appreciated. To God be the glory!

Tom Ingebritsen is an Associate Professor Emeritus in the Dept. of Genetics, Development and Cell Biology at Iowa State University. Since retiring from Iowa State in 2010 he has served as a Campus Staff Member with InterVarsity Graduate & Faculty Ministry at Iowa State University

Leave a Reply