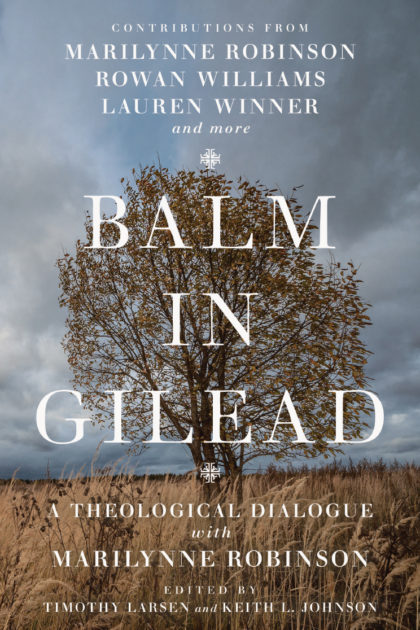

In an essay on Dietrich Bonhoeffer, [Marilynne] Robinson declared that "great theology is always a kind of giant and intricate poetry, like epic or saga. It is written for those who know the tale already, the urgent messages and the dying words, and who attend to its retelling with a special alertness, because the story has a claim on them and they on it. Theology is also close to the spoken voice." In Gilead we are indeed listening, or rather overhearing, the dying words of the venerable, ailing, seventy-six-year-old … [Read more...] about Great Theology, Teachableness, & John Calvin [Balm in Gilead / Summer Read…Quote…Reflect]

dietrich bonhoeffer

A Nation of Immigrants. Part 5 of Welcoming the Stranger Series

Immigrants today, whatever their manner of entry, come primarily for the same reasons that immigrants have always come to our country. Though immigration policies have changed quite drastically over the last two centuries, immigrants themselves are still pushed out of their countries of origin by poverty, war, and persecution, and are still drawn to the United States by promises of jobs and economic advancement, freedom, and family reunification. These push and pull factors explain most, if not all, of immigration to … [Read more...] about A Nation of Immigrants. Part 5 of Welcoming the Stranger Series

Second Week of Advent: The Hope (Scholar’s Compass)

Scripture Oh that you would rend the heavens and come down, that the mountains might quake at your presence— as when fire kindles brushwood and the fire causes water to boil— to make your name known to your adversaries, and that the nations might tremble at your presence! —Isaiah 64:1-2 (ESV) … [Read more...] about Second Week of Advent: The Hope (Scholar’s Compass)

Overnaming as The Fall

In this four-part series, I aim to think about one particular aspect of language: naming. In the introduction, I preliminarily addressed the root of the problem, the Fall. In this post I want to dive deeper into the original ‘scene of the crime' for clues toward the character of the relationship between language and naming. … [Read more...] about Overnaming as The Fall

Why Might Christians Be Involved in Nonviolent or Violent Protests? Lessons from Ukraine’s Euromaidan Protests at Urbana

How can Christians decide when to be involved in conflict, and how can they know when to stop? In the past two years, Christians in Ukraine have faced all of these. How have they responded? From Dec 27 - Jan 1, volunteers with our network of early career Christian academics are liveblogging seminars at the Urbana conference, a mission-focused student gathering of 16,000 Christians from across North America and the world. This post was written by Nathan Matias and Galina Pylypiv … [Read more...] about Why Might Christians Be Involved in Nonviolent or Violent Protests? Lessons from Ukraine’s Euromaidan Protests at Urbana