How can Christians decide when to be involved in conflict, and how can they know when to stop? In the past two years, Christians in Ukraine have faced all of these. How have they responded?

From Dec 27 – Jan 1, volunteers with our network of early career Christian academics are liveblogging seminars at the Urbana conference, a mission-focused student gathering of 16,000 Christians from across North America and the world. This post was written by Nathan Matias and Galina Pylypiv

In late November 2013, thousands of Ukranians gathered in the capital city Kiev to protest the sudden reversal of a historic partnership with the EU and oppose a deal with Russia. Citizens of this country (which regained independence at the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991) gathered at a scale that prompted comparisons to the Ukraine’s peaceful 2004 Orange Revolution. After brutal government attacks on protesters in early December, the Euromaidan protests turned more violent and continued until the removal of president Viktor Yanukovych in late February 2014. One month later, Russia invaded and annexed Crimea, the southern region of Ukraine, sparking a war between the two countries. (To learn more, see the BBC timeline and coverage by Global Voices of the #Euromaidan protests). Speaking today is Yevgen Shatalov, who is general secretary of the fellowship of Christian students in Ukraine. He’s written about the Euromaidan movement for the International Fellowship of Evangelical Students.

Should Christians Challenge The State?

Should Christians challenge the state? To set up this question, Yevgen tells us a story from the book Hitler’s Cross by Erwin W. Lutzer, about a church near a railroad in the second world war. Every Sunday, a whistle would blow, a train would stop, and the churches would hear screams. The Christians were upset because they couldn’t worship over the sound of the screams. Since they knew the time of the train, they decided to sing hymns at the time that the train passed by. If they heard people screaming, they would sing louder, and they sang until the train passed by. According to Lutzer, “The Church lost sight of its mission in society” because it ignored the problems. Yevgen contrast this with the approach of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, who argued that while Christians can focus on healing the wounds done by the machine of the state, they should also be involved in breaking the machine. “Silence in the face of evil is itself evil: God will not hold us guiltless. Not to speak is to speak. Not to act is to act,” wrote Bonhoeffer.

Christians in the Euromaidan Protests

To learn more about the Euromaidan protests, Yevgen encourages us to watch the Netflix documentary “Winter on Fire.” In this talk, he focuses on the church in Ukraine and student Christian involvement in the movement. To start, Yevgen says, we need to understand that the church in Ukraine was under the communist regime for 70 years, a regime that shot Christians and sent them to Siberia. Since the government couldn’t erase Christianity materially, they tried to erase it culturally. Christians were prohibited from studying at universities, prohibited from doing religious activities outside the church, and Christians could be arrested if they said the wrong things. To protect itself, the church became separated from society, maintaining their religious sincerity but not having influence on society. The church narrowed their idea of mission to focus solely on life after death, says Yevgen, resulting in cultural and political isolation. As the Soviet Union collapsed, the church continued with this inertia. Then in November 2013, then-president Viktor Yanukovych refused to sign an agreement with the European Union, one that he had promised to sign. At the time, Ukraine was the 144th most corrupt country, according to Transparency International, next to Uganda and Bangladesh. You could buy anything in Ukraine says Yevgen: a judge, a cop, a law. Many Ukranians looked to closer ties to the EU as a possible response to the problem of corruption. So when the president refused to sign promised agreements with the EU, they realized that Ukraine would only get worse. On Nov 21, students in Kiev and many other cities gathered for a week of peaceful protests. On November 30, the president brought in special forces who beat protesters with batons, chasing unarmed protesters, and even kicking and beating protesters who fell to the ground while trying to escape. They also attacked women and journalists. Ukraine hadn’t seen such brutality before, and the protesters fled through the city. Yevgen tells us the story of Alexander, a Christian student leader. “As police started beating us, I got hits on my back and fled up the hill. I practice sports and am a good runner, so I was able to get rid of them.” The next morning, Ukranians saw the images and were disturbed, especially because they knew that their students were protesting there — many Christian students were beaten for nothing. The next day, around 1 million people across Ukraine gathered in the square looking for justice to take place. They filled the streets and closed the roads, asking the president to sign the EU agreement and punish those who attacked the students. The president was silent.

Can Christians take part in protests against the authorities, if “all authorities are from God”?

Of course Christian students went to the streets says Yevgen. But it’s a controversial topic in Christianity, because it seems like the scriptures encourage people to obey authorities. Christians cited the teachings of Paul in Romans 13, that everyone should obey and be subject to rulers, who receive their authority from God. Imagine that your friend is committing a sin, asks Yevgen. You would work to convince your friend by talking to him. But what if your president is committing corruption? Do you have a role to tell the president he’s wrong? Traditionally, Ukrainians would say, “well, let’s just pray. It’s not our place to say that.” The events around Euromaidan challenged the Christian church to rethink these issues.

To unpack these questions, Ukranian Christians from multiple denominations, along with the Ukranian Christian student group, organized a gathering of notable Ukranian theologians to discuss the issues in late January, 2014. They concluded that Paul’s comments in Romans 13 didn’t actually mean that Christians couldn’t protest. In Paul’s time, people didn’t have the right to influence the government. But the Ukranian constitution claims that all authority belongs to the people, not the president– in this case, the president was not truly in authority. Yevgen also talks about the Christian cultural mandate going back to Genesis to “subdue to the earth” and steward it well in all its fullness. As Christians, we still have this mandate, he says. He cites Goheen and Bartholemew’s book Living at the Crossroads: “The good news will be evident in our care for the environment, in our approach to international relations, economic justice, business, media, scholarship, family, journalism, industry and law.” After this gathering, pastors from multiple denominations signed an agreement that the church should be a prophetic voice for society, protesting against evil. Churches began by giving away hot tea, food, and Bibles at protests. They also set up prayer tents in protest areas. Christians became part of the protests as well, and in the course of the protests, they were beaten severely many times by police, even though they were peaceful, says Yevgen. Then a turning point was reached. The parliament passed anti-protest laws, which were widely criticized internationally. These laws would have led the Christian student groups of Ukraine to cease to exist. At that point, protesters started to use violence against the police, mostly burning tires. This created another challenge for Christians.

Should Christians Engage in Violent Protest?

Yevgen shows a photo of Ghandi, Jesus, and Martin Luther King, asking for the connection between the three. On one hand, in Matthew 5, Jesus tells people, “do not resist an evildoer” and to turn the other cheek. On the other hand, asks Yevgen, can’t you use the power of force for self defence? How do self defence and non-violent resistance connect?

Ukranian Christians and pastors studied these passages and looked at the history of revolutions. They decided that Jesus doesn’t teach us to be passive. Instead, he teaches us not to use the same force against the person who attacks you. In the case of turning the cheek, this is a response to the person who hit you — a different kind of response. We’re called to respond to violence, but to use nonviolent methods of response. Yevgen pauses. “This is a difficult topic…… especially when your friends are being beaten. How is it possible to be peaceful?” Also, we know that peacemaking and the idea of “Shalom” is one of the main themes of the New Testament, and that Jesus said “blessed are the peacemakers” (Matthew 5:9) and that “Peacemakers who sow in peace raise a harvest of righteousness”) (James 3:18). How is it possible to bring peace in a revolution or a war?

Yevgen says that he could not support protesters injuring police, but that Christians could also not be passive. Peacemaking isn’t about creating friends out of enemies. It’s about recognizing a problem, arguing that it can be solved, and suggesting solutions. Christians needed the wisdom to protect police from protesters and to protect police from protesters in a wise and nonviolent way. When protesters and police clashed in front of the Lutheran church during a service, the pastor walked outside and stood between protesters and police. He recognized that Christians had an opportunity to protect them from each other and call them to see that each other were not the wider problem. Police lines are like a machine that can’t be stopped says Yevgin, but they sometimes stopped in front of the priests.

In this particular moment, Christians realized that standing between protesters and the police would be one way to at least pause and delay conflict. He shows us photos of Christians of many denominations creating living walls to protect two parts from one another. When asked, “what if you’re injured or die,” the people in the living wall were willing to accept it.

Another way that Christians served others was to prepare people for burial. Yevgen reminded us that in the last days of the protest, police started using live rounds and killed over a hundred protesters in one day. When Yevgen saw images of a dead protester, he was reminded of the image of Christ dying on the cross– in some sense, protesters offered their bodies for a higher cause. During the last days of the protests, priests and protestant pastors would pray with them and give them confession before they went to the front lines to be shot. Sometimes you know that when you share the gospel with a person, says Yevgen, you know that you might have a conversation with them over many years; in this case, Christians were preparing people for death, to prepare them to become offerings for the common good.

The parliament voted to remove president Yanukovych from office and he fled the capital on February 22; the revolution was over. Currently, the top five people in the government are Christians. After the revolution, the Christian church received the highest rating in public trust of any institution, which has never happened before, says Yevgin. Christian student ministry is now moving into a new stage, because they chose the side of Dietrich Boenhoffer, rather than the story of the Christians who accommodated the holocaust.

The story isn’t over; just after the revolution concluded, the Crimea was occupied by Russia. Yevgen’s home city was destroyed and it’s now occupied by Russian-backed separatist groups. Yevgen says that the revolution prepared Christians and Christian students for the war that came later.

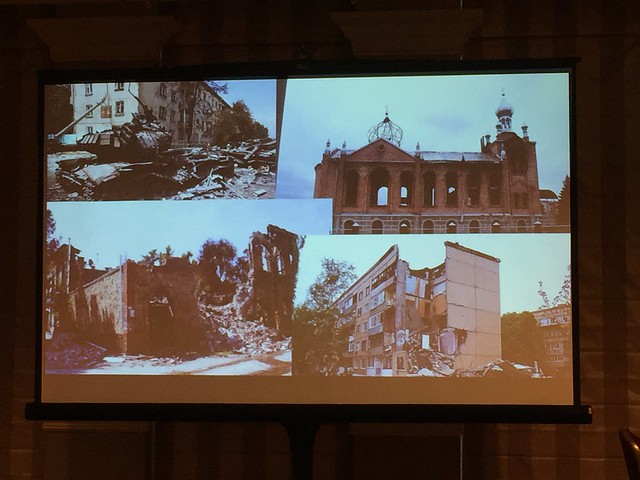

Images from Yevgen’s home city, which has been mostly destroyed in the war with Russia

Are the lessons from Ukraine universal? Should all Christians behave in similar ways? Yevgen argues that it’s important for Christians not to flee the problems, and that Christians should meet together and make unified decisions about their political engagement at times like this.

Questions and Answers

When you mention Christians that are in authority, are they the protestant evangelical Christians, or are you including orthodox? Those Christians are mostly catholic, protestant, and orthodox, says Yevgin.

In some Slavic countries, people differentiate their identity by their sect of religion; how is that in Ukraine?

The majority of people in Ukraine think of themselves as Orthodox. We also consider our religion as part of our identity. Because I represent IFES in Ukraine, says Yevgen, it’s usually protestant students. University administration sometimes think of us as a sect, but that’s a very Soviet understanding. One of the top NGOs working against corruption is run by a protestant.

What was the role of the pentecostal church, if any, in the demonstrations? The pentecostal church is very conservative. The first challenge was the most difficult– they try to live according to the scripture, and they would interpret Romans 13 literally, and they wouldn’t support any protests. As the roundtable discussions unfolded and we gave pentecostals a chance to sign an agreement, the church officially joined. But they are the minority, says Yevgen.

A student from Hong Kong reports facing similar things in the Umbrella revolution. Many people say that by protesting, you’re fostering social divisions and instability. Yevgen notes that the former president used that as a justification for removing protesters. It’s true that protesters make things unstable– but sometimes it’s important to shake the machine. You have a strong machine where you are, but we agree that it’s important to shake the machine as we fight for truth.

How can Christians know if they’re on the right side? In the Umbrella revolution in Hong Kong and the Sunflower movement in Taiwan, there are Christian friends who join, but other churches stay out. Yevgen says that they felt very similar at the beginning. Many Christians thought about stopping. For Yevgen, the important thing is to agree on a cause– regardless of politics, everyone agreed that the students shouldn’t have been beaten. When things are more political, it can be more difficult (the Orange revolution divided the church), but people were united in their appeals for justice during the Euromaidan protests.

Did the revolution change the relationships between churches? Usually, churches in Ukraine don’t cooperate very much. Pentecostals don’t always work well with Charismatics, for example, and Lutherans and Orthodox can look askance at them, says Yevgin. But during the revolution, when people were driven to prayer together and preach together, there was a positive sense of ecumenism.

The former president was predominantly supported by eastern side of the country. How can there be unity between the eastern and western churches?

Even though it’s true that you can theoretically divide Ukraine into West and East, Yevgen says that it’s not true of Christianity. Yevgen comes from the most eastern part of the country, in an area that hate Poroshenko, the current president. Christians have also been shot by the Russian-backed groups because they were giving food to Ukranian troops who were standing on the border. Christians always try to distance themselves from politics, says Yevgen. Sometimes this can be bad, but it does make them skeptical about propaganda. The only exception, he says, would be some orthodox priests in the east associated with the Moscow Patriarchy, and who support the separatist groups (Al Jazeera covered this divide in an article on conflicts of faith in Ukraine earlier this week).

As Christians in a context of war, how should we think about the war on terror and anti-muslim propaganda? How can Christians respond to this machine of violence? Yevgen says that the war in Ukraine happened because of Russian propaganda that was very active on the east, and people didn’t understand what was happening in the rest of Ukraine. When Russian-backed separatists entered the city, Christians didn’t do anything, Yevgen sadly remarks. He argues that Christians have the obligations of citizens and an obligation to tell the truth, not only about God but also about what is happening in your country. Christians can be involved in things like this by creating roundtable conversations, and by countering propaganda. He encourages Christians to seek God for wisdom on what to do. Christians are not temporary residents, but they are citizens, he argues.

J. Nathan Matias (@natematias), who recently completed a PhD at the MIT Media Lab and Center for Civic Media, researches factors that contribute to flourishing participation online, developing tested ideas for safe, fair, creative, and effective societies. Starting in September 2017, Nathan will be a post-doctoral researcher at the Princeton Center for Information Technology Policy, as well as the departments of psychology and sociology department

Nathan has a background in technology startups and charities focused on creative learning, journalism, and civic life. He was a Davies-Jackson Scholar at the University of Cambridge from 2006-2008.

Leave a Reply