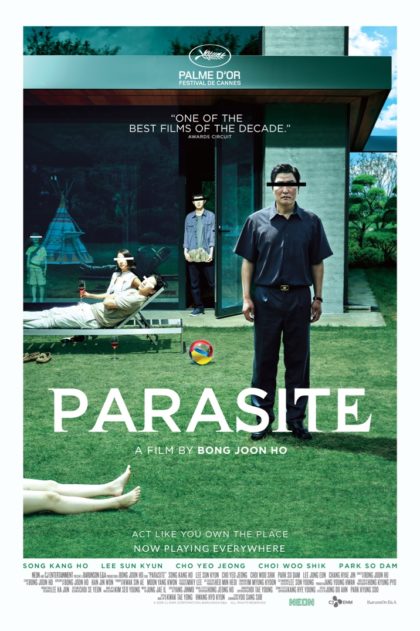

Many thanks to Drew Trotter of the Consortium of Christian Study Centers for his thoughtful reflections on the 2020 Academy Awards Best Picture Nominees. He wraps up the series today with Parasite. For the whole series, click here. To learn more about Drew's work with The Consortium of Christian Study Centers, or to look for Christian study centers near your campus or study guide and film resources, click here. Parasite (R, 132 mins.) Director: Bong Joon Ho. Writer: Bong Joon Ho (story and screenplay), Jin Won … [Read more...] about Oscars Film Reflection Series: Parasite

Oscars 2020 Series

Once Upon a Time’ in Hollywood

In an ongoing series, Drew Trotter of the Consortium of Christian Study Centers is sharing his reflections on this year's Academy Awards Best Picture Nominees. For the whole series, click here. Once Upon a Time’ in Hollywood (R, 161 mins.) Director: Quentin Tarantino. Writer: Quentin Tarantino. Cast: Leonardo DiCaprio, Brad Pitt, Margot Robbie, Emile Hirsch, Margaret Qualley, Timothy Olyphant, Dakota Fanning, Bruce Dern, Al Pacino, Lena Dunham. Genre: Comedy, Drama. Plot Outline: A faded television … [Read more...] about Once Upon a Time’ in Hollywood

Oscars Film Reflection Series: 1917

In an ongoing series, Drew Trotter of the Consortium of Christian Study Centers is sharing his reflections on this year's Academy Awards Best Picture Nominees. For the whole series, click here. 1917 (R, 119 mins.) Director: Sam Mendes. Writer: Sam Mendes, Krysty Wilson-Cairns. Cast: Dean-Charles Chapman, Charles MacKay, Daniel Mays, Colin Firth, Mark Strong, Benedict Cumberbatch, Richard Madden. Genre: Drama, War. Plot Outline: Two young British soldiers during the First World War are given an … [Read more...] about Oscars Film Reflection Series: 1917

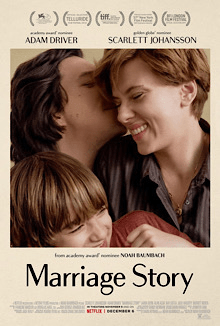

Marriage Story

In an ongoing series, Drew Trotter of the Consortium of Christian Study Centers is sharing his reflections on this year's Academy Awards Best Picture Nominees. For the whole series, click here. Marriage Story (R, 137 mins.) Director: Noah Baumbach. Writers: Noah Baumbach. Cast: Adam Driver, Scarlett Johansson, Laura Dern, Alan Alda, Azhy Robertson, Ray Liotta Genre: Comedy, Drama, Romance. Plot Outline: Noah Baumbach's incisive and compassionate look at a marriage breaking up and a family staying … [Read more...] about Marriage Story

Oscars Film Reflection Series: Little Women

In an ongoing series, Drew Trotter of the Consortium of Christian Study Centers is sharing his reflections on this year's Academy Awards Best Picture Nominees. For the whole series, click here. Image Credit: Promotional image, from image gallery at official film site (Fair Use: Criticism) Little Women (PG, 135 mins.) Director: Greta Gerwig. Writer: Greta Gerwig (screenplay). Louisa May Alcott (novel). Cast: Saoirse Ronan, Laura Dern, Emma Watson, Florence Pugh, Eliza Scanlon, Timothée Chalamet, Tracy Letts, … [Read more...] about Oscars Film Reflection Series: Little Women