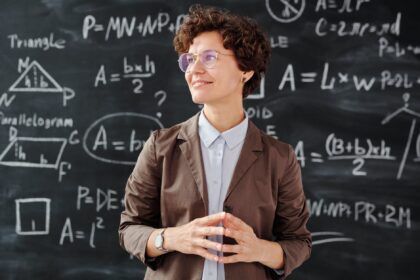

As scholars, we train rigorously in our fields, and learn to communicate with each other, but not the people most impacted by our work. How can we learn to do better? The world and the Church need us. I’m an academic, but I spend more time writing for lay audiences than scholarly ones. I’ve done my share of academic writing, from undergraduate essays, to grant proposals, science articles, and poster presentations. I even teach students how to do this. As a science communicator, I’ve realized that there is a … [Read more...] about Five Tips for Academics on Communicating to Lay Audiences

A Prayer for Adjuncts and Contingent Faculty

Over the years, ESN has published prayers for various field areas and seasons of academic life. From searching the archives, this appears to be the first (and long overdue) time we have posted a prayer for adjunct and contingent faculty. Thank you, Ciara Reyes-Ton, for sharing this prayer! Thank you, God, for the opportunity we have to serve our students and institutions of higher learning. Whatever the circumstances that have brought us to our current position of contingency, whether we are working towards a more … [Read more...] about A Prayer for Adjuncts and Contingent Faculty

Science Draws Me Closer to God

Join ESN for a conversation with Ciara-Reyes Ton and Andrew Rick-Miller, co-director of Science for the Church for a conversation on science, faith and a better conversation between scientists and the church. The conversation is on Wednesday January 25 at 4 pm ET. Sign up at https://tinyurl.com/ESNSciFaith. Science draws me closer to God. It didn't always though. At first it seemed irrelevant. Science inhabited a different domain than things of the spirit and scripture. I kept them compartmentalized, in part because … [Read more...] about Science Draws Me Closer to God

How is Our Knowledge of the Natural World Similar to/Different from Our Knowledge of God? (STEAM Grant Series February Question)

Question: How is our understanding of faith and God different from our understanding of the natural world? How is it similar? This academic year, ESN is creating a Faith/Science curriculum for young adult small groups. We're partnering with InterVarsity graduate student discussion groups to identify faith/science questions that are important to emerging scholars, and then commissioning thoughtful Christians in science or theology/philosophy to explore those questions in a series at the ESN blog. We will … [Read more...] about How is Our Knowledge of the Natural World Similar to/Different from Our Knowledge of God? (STEAM Grant Series February Question)