This is Part 2 in a five-part essay series. A version of this essay was originally published online and in print as part of “Faithful Presence in the Midst of Pluralism: Three Tensions” at Ad Fontes.

The call to faithful presence in the midst of deep pluralism, in and beyond higher education, requires us to learn to learn to live with certain unresolvable tensions. The first of these tensions is affirmation and antithesis.[1]

Affirmation involves explicitly recognizing and celebrating whatever is good, true, and beautiful in human cultural activity, regardless of its religious, spiritual, or ideological orientation. For example, a Christian might read a Zen Buddhist haiku as a window into “God’s marvelous creation and the glories inherent in each moment,”[2] while recognizing that Zen Buddhism and Christianity are not, ultimately, fully compatible with one another.[3] To acknowledge this final opposition is to engage in antithesis. Yet antithesis goes beyond simply analyzing the opposition between incompatible worldviews: more importantly, antithesis highlights the alternative interpretation that Christianity offers, as when we resituate a Zen haiku in the context of the glorious work of the Creator God.

The practice of affirmation rests on the theological concepts of creation and “common grace,” meaning the many good gifts of God that are shared by Christians and non-Christians alike.[4] Common grace includes natural goods, such as rain and sun; relational goods, such as children and friends; and especially cultural goods, such as science, the arts, government, and education. The concept of common grace opens Christians up to affirm the goodness of many aspects of cultural activity, including the efforts of non-Christians. Furthermore, it leads us to see all aspects of human creativity as enabled by God the Creator.

Yet affirmation leads directly and necessarily to antithesis. In almost the same breath as Christians affirm that the world and human culture are good, we also acknowledge that the world is fallen and humans are sinful. The Reformed tradition in particular emphasizes the doctrine of “total depravity,” which means not that everything humans do is evil, but rather that the taint of sin touches every aspect of human existence. As James Davison Hunter says, “Antithesis is rooted in a recognition of the totality of the fall.”[5] Although it is individuals, not cultures or ideas, who are depraved, the effects of that depravity can be felt in all that humans do. For this reason, many aspects of cultural and intellectual activity —including certain artistic expressions, philosophical assumptions, and political arrangements —are fundamentally at odds with Christianity. So we cannot affirm everything about human culture, but will seek to reveal the antithesis between Christianity and other competing systems of belief, value, and practice.

Yet Hunter emphasizes that “antithesis is not simply negational. Subversion is not nihilistic but creative and constructive.”[6] Therefore, antithesis involves not only showing the conflict between Christian and non-Christian worldviews but also developing the Christian worldview as an appealing alternative to other patterns of thought and behavior. In this way, antithesis leads back to affirmation, recognizing much that is praiseworthy in non-Christians’ pursuit of art, scholarship, justice, and other areas of human culture. Similarly, affirmation always leads directly to antithesis: it does not merely recognize the goodness in non-Christians’ cultural activities, but also resituates that goodness in the context of God’s gracious gifts. Thus, these two attitudes cannot exist independently of one another, but each must continually feed into the other.[7]

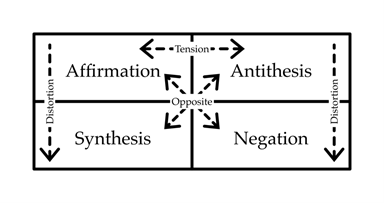

Both the interconnectedness of and the enduring tension between affirmation and antithesis can be seen more clearly by means of contrast with two other attitudes which often masquerade as affirmation and antithesis but are in fact perversions of them. These are negation and synthesis. Hunter explains that antithesis is “constructive opposition, representing a contradiction and resistance but with the possibility of hope.” In contrast, “the concept and practice of ‘negation’ have become expressions of nihilism. It offers nothing beyond critique and hostility. It is antagonistic for its own sake. This, it would seem, is contrary to the gospel.”

Just as negation is the distortion of antithesis in the absence of affirmation, so also the distortion of affirmation in the absence of antithesis is synthesis, which “is problematic because it presupposes a blending and an accommodation with that which it opposes.” Hunter reconnects affirmation with its essential counterpart antithesis, reiterating that affirmation “does not require assimilation with its opposition to validate actions or ideas generated by the opposition of which it approves.”[8] Thus, as the figure below illustrates, affirmation and antithesis can only truly be affirmation and antithesis when we pursue them both together. As soon as we neglect affirmation in favor of antithesis, we no longer even have antithesis, and vice versa. It is for this reason that faithfully living out this tension is a “precarious dance.”[9]

The tension between affirmation and antithesis[10]

[1] Those who are familiar with the Neo-Kuyperian stream in Reformed Christianity may recognize similarities between this tension and that tradition’s distinction between structure and direction.

[2] James W. Sire, Naming the Elephant: Worldview as a Concept, 2nd ed. (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2015), 174.

[3] Sire, Naming the Elephant, 172.

[4] Common grace is distinguished from special or saving grace, which belongs to Christians alone. For a discussion and critique of the language of common grace in Reformed Christian circles, see James K. A. Smith, Awaiting the King: Reforming Public Theology (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 2017), 122-124.

[5] James Davison Hunter, To Change the World: The Irony, Tragedy, and Possibility of Christianity in the Late Modern World (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010), 234.

[6] Hunter, To Change the World, 235.

[7] In Hunter’s words, affirmation and antithesis are two movements in a single dialectic. See Hunter, To Change the World, 231-236.

[8] Hunter, To Change the World, 332n7.

[9] Smith, Awaiting the King, xiii.

[10] Figure courtesy of Luke Herche. Used by permission.

Emily G. Wenneborg is Director of Pascal Study Center and Assistant Professor at Urbana Theological Seminary. She has a PhD. in Philosophy of Education and Religious Studies from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Emily is interested in the possibilities and tensions of formation for Christian faithfulness in the midst of deep pluralism.

Leave a Reply