. . . Scripture suggests that all of us who follow Christ, whatever our nationality, have become aliens in this world, as our allegiances are to lie not primarily with any nation-state but with the kingdom of God. Paul reminds the believers at Philippi that their citizenship is in heaven (Phil 3:20), while Peter (1 Pet 2:11) and the author of Hebrews describe believers as foreigners and strangers on earth (Heb 11:13).

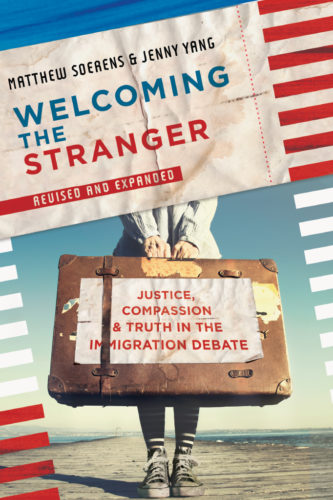

God used migration throughout Scripture to accomplish his purposes and bring his people to a greater understanding of his will for creation. God, who used migration so vividly throughout the Bible, works today to move his people from one place to another. – Soerens and Yang (2018), “Thinking Biblically About Immigration,” Chapter 5 in Welcoming the Stranger, p. 89.

Chapter 5 Summary

I am a facilitator for a 3-year discipleship course at New Psalmist Baptist Church here in Baltimore. Before becoming a facilitator, I was of course a student in the course, and my own facilitators would often ask us our opinion on a topic or an issue. And then, after we offered our opinion, our facilitators would ask: “Now, what does the Word say?” It was as if to say that they were okay giving us an opportunity to speak our minds, but after expressing our opinion it was now time to consult the real authority—the Word of God—so as to direct our thoughts and our conduct on whatever issue it was we were talking about.

In Chapter 5, we are the discipleship students and Matthew Soerens and Jenny Yang are our facilitators. They’ve allowed us to speak our minds some in Chapters 1 and 2 as we described what got us interested in this topic. Chapters 3 and 4 helped us to understand a bit more about exactly how large the issue is. Now in Chapter 5, they’re asking us to set aside our opinions for a moment and are plainly saying to us: “Now, what does the Word say?” And on this issue, the Word is profoundly challenging to us. Quoting Orlando Espin, Soerens and Yang point out that “Welcoming the stranger is the most often repeated commandment in the Hebrew Scriptures, with the exception of the imperative to worship only the one God.” (p. 85)

Chapter 5 describes how God frequently—in both Old and New Testaments—commanded his people to migrate from one place to another in doing his will. In one account, Abram is commanded to leave Ur for Haran, and later proceed to Canaan. If only we could imagine just how treacherous and shocking this command actually was! God asked Abram to leave the security of his family and their possessions to go to a land that was not yet identified to him. In order to migrate to this land, they would have certainly encroached on the land of others and have been viewed with suspicion that might have gotten him and those belonging to him killed. In fact, Abram hints at these fears when the Bible describes how Abram lies about his relationship to Sarah in order to avoid attack.

We see the immediate vulnerability of migrants in the Bible in another account when we look at the account of Jesus’ early life. His parents, Joseph and Mary, were forced to leave their ancestral homeland of Judah for Egypt in order to avoid certain death for their newborn son. Yet, despite the immediate dangers to Abram and Sarah, Joseph and Mary, God used their migration for good to those who love God and are called to His purpose (cf. Romans 8:28). As Robert Chao Romero describes in his article, “Migration as Grace,” migration can be a blessing to both the migrant and the societies where they settle and contribute. This is an important concept to remember when thinking biblically about immigration, and resides in the background of many of our common Christian teachings and exhortations. For example, many of us may have heard Jeremiah 29:11 quoted as a form of blessing or invocation of God’s favor. However, in the immediate context of that verse, God commands that Israel should pray that the places where they have been settled in exile might be blessed! This means that Israel’s forced migration by exile was in fact also a means of God’s grace to Babylon.

The long and short of Chapter 5 is that God takes special concern for the foreigner and stranger because of their unique vulnerability. The Israelites were to have the same law governing both native and foreign-born. The Israelites were to provide means for assimilation of foreigners into the Israelite society. The Israelites were to ensure provision for the foreigners’ physical needs by being sure to pay their wages in a timely way and not harvesting crops so efficiently as to leave nothing for the migrants or vulnerable to glean from the fields. If this special concern was not extended to the foreigner, the Israelites could expect the judgment of God to fall on them because they themselves had history as foreigners and exiles in Egypt, yet have become perpetrators of the same injustices and oppression they themselves had faced.

This chapter, in both the 2009 and 2018 versions of the book, is so rich that a full summary is just not possible here. Even my summary is quickly turning aside to reflection, as I turn their teaching over in my mind. I’d almost have to write my own full article just to discuss what Soerens and Yang present. It was my favorite chapter in the original, and it is one of my favorites in the revised version. I urge you to read it for yourself and reflect on the Scriptures for yourself.

Key Discussion Questions

- How should our heavenly citizenship dictate the way we view and treat immigrants in our churches? How about in our schools and communities?

- How does Jesus respond when he is asked, “Who is my neighbor?” How does his response inform how we view immigrants?

Reflection

Thinking biblically about immigration is full of challenging questions that will require a large amount of time to master. Also a large amount of courage. For, although immigration is a technical topic with many very arcane details, the popular discourse is full of the expressions of our collective hearts. Our response to the immigration challenge is a test of our discipleship and transformation to Christ’s likeness. I say this because the Bible seems to be calling for a type of generosity that would very quickly become unwieldy in practice. As with most things, it becomes exceedingly difficult to lay one’s life down on the one hand while seeking to preserve it with the other. Isn’t this what we do with so many things in life? I may be talking about immigration right now, but there are so many examples of things we enjoy that God may be calling us to loosen our grip on. We reach out to any and everything to justify holding on tight, when our resistance to the call to let go shows unequivocally how much of a grip our privileges or possessions have on us.

The first thing we do well to remember is to reflect on just how vulnerable immigrants—documented and undocumented, wealthy or poor—often are. As I write this, I’m reminded of how, in The World Until Yesterday, Jared Diamond describes how the ease with which we routinely travel across tribal and cultural boundaries—sometimes thousands of miles as I am currently doing while I write this above the Atlantic Ocean—without peril or danger to ourselves has not been possible in most human cultures until very recently. Foreigners could be viewed with suspicion and often killed or treated harshly in order to protect the tribe from outsiders or potential danger. As we read the Bible, context gives clues that allow one to conclude that being a foreigner meant to be dispossessed of most earthly rights and property, and to be almost entirely vulnerable under law or local custom. Even Paul, who apparently sometimes decided not to use his own Roman citizenship to his advantage, was subject to the state of vulnerability foreigners might have found themselves in. In some important ways, many classes of immigrants find themselves in similarly vulnerable situations to varying degree. Many Christians are not quite sure how to respond to all of this, though, because legal and political concerns to which they may be held accountable make it difficult to determine the proper action to take. While there have always been clashes of identity and responsibility, whether taking the form of membership of a tribe or citizenship in a nation state, Jesus calls us to review these boundaries when he asks “Who is my neighbor?”

Suppose we know who our neighbor is. Well, the biblical mandate to welcome the stranger is still very difficult because it is going to cost something. Sometimes, that cost can be great. While immigrants, on the balance, contribute positively to the national economy, undocumented immigrants may increase the cost of local services such as emergency medical care and public schooling. More importantly, it is going to personally cost us in getting to know one another and becoming entangled in one another’s affairs. In neighborhoods where immigrants settle, the local culture and social life will change. Those who have lived there before new arrivals will pay a cost as their environs become unfamiliar. Churches will have to do the difficult work of preaching and being the Gospel in increasingly diverse communities. They will need to lead as we seek to answer the question: “How should the biblical commands to care for the stranger and foreigner in the ancient Israelites’ midst be applied today?”

Peace and Blessings,

Royce

Editor’s note: Pray for Royce’s training as he prepares to run the Baltimore Half Marathon in support of World Relief. Stay tuned for updates. Go Royce!

Royce is an associate professor of engineering management and systems engineering at the George Washington University. He conducts and teaches under the broad theme “SEEDâ€: Strategic [urban] Ecologies, Engineering, and Decision making. His research and teaching interests include infrastructure sustainability and resilience measurement, risk analysis, and drinking water systems analysis. Royce is a member of the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE), and the Society for Risk Analysis (SRA).

Leave a Reply