This week we observe the 500th anniversary of Martin Luther’s hammer stroke heard ’round the world, a milestone in the broader Reformation movements that redefined the European landscape for centuries. While Luther’s concerns were theological, change came to many corners of the cultural world, even the sciences. Thus even a notable scientific journal like Nature is sharing a remembrance of Luther, albeit with the twist that maybe the emergence of Protestantism did not influence science so much as we might think.

There is no question that the past 500 years have been extremely productive for science. In fact the set of cultural activities and methodologies that we currently consider science, as well as most of the facts we learn from our science textbooks, emerged in their recognizable form during that period. Notable scientists from Isaac Newton to James Clerk Maxwell to Francis Collins are part of the Protestant tradition. At the same time, one of the general principles of the Reformation movements was a democratization of knowledge consistent with the principles of science and necessary for its practice, as we discussed while reading through The War On Science. The Bible was translated into vernacular languages and believers were encouraged to read it for themselves. Luther and other reformers rallied public support for their causes by printing and distributing pamphlets, rather than relying solely on discourse within the academic and theological communities. This synergy of values and overlap of outcomes encourages drawing further connections.

David Wootton, in the Nature piece, acknowledges these correlations. However, like any scientist, Wootton is wary of inferring causation and concerned with the possibility of a confounding effect — an underlying causal factor driving both observed scenarios that explains their connection. Wootton proposes that other developments, including the invention of the printing press and the (re)discovery of the American continents, made Europe ready for both religious reform and scientific revolution. Either one could have happened without the other, but both depended on ready access to identical copies of mass-produced publications, for example.

I’ll leave it to the historians to decide how to assign responsibility. I did think Wootton made some good points, especially when he notes the significant contributions the Catholic church and individual Catholic believers have made and continue to make to the scientific revolution. Through the Middle Ages, Catholic scholars preserved and extended classical investigations into the physical world. Plenty of notable scientists before and after Luther were Catholics, including Blaise Pascal and Gregor Mendel and Georges Lemaître. The current pope came from a background in the sciences. As Christian traditions, both Protestantism and Catholicism share theology encouraging the practice of science, including belief in a creator God who orders the world in a way that can be investigated and understood and liturgical recognition and appreciation of specific details of creation.

Of course there is the case of Galileo, a Catholic scientist and frequently the first (or only) person anyone mentions when discussing the history of science and religion. Yes, Galileo argued that the earth orbited the sun rather than the other way around, contrary to both church doctrine and classical science. And yes, the church censured him — although not solely on theological or dogmatic grounds. As science, early heliocentric models did not agree with observations as well as the geocentric models that had been refined for centuries to match the data. If we apply the skeptical dictum that extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence, the extraordinary move of taking the earth out of the center of the cosmos requires a compelling evidentiary case. That evidence would come, but it’s not entirely surprising that the church leaders had stringent criteria for making a change. Those criteria don’t necessarily justify all of their actions, but they do paint a more complicated picture of an institution interested in both science and doctrine.

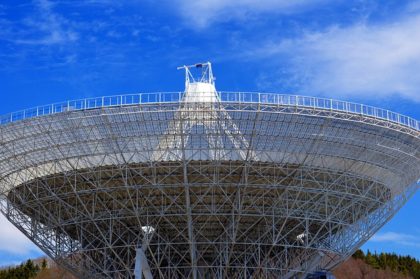

Wootton notes another dynamic in the scientific revolution, the transition from textual study of Aristotle and other classical thinkers to direct empirical observation. One can identify this as the line between natural philosophy and science proper. With Galileo, it was looking more closely at the stars and planets and seeing objects like the moons of Jupiter that just cannot be seen unaided. Steady improvements in telescope technology make more and more distant, and thus older and older, objects available for study. The scale of our investigations increases along the way; it was less than 100 years ago we learned that our galaxy is not the only one. Flip a telescope around and you’ve got a microscope, opening up smaller and smaller scales.

In principle, these technologies are available to everyone. And indeed many homes have their own telescope or microscope — or chemistry set or circuit building kit. At the same time, few in practice have access to the equipment and materials involved in modern scientific inquiry. I’m reminded again of The War on Science and the suggestion that anyone can get a mass spectrometer for $2,000 and confirm the age of the earth for themselves. I simultaneously want to live in a world where that is a reality and question whether that scenario is even remotely feasible. In practice, most people do not, cannot and will not be able to make the observations upon which major scientific conclusions are based.

Whatever the connections between the Protestant reforms and the scientific revolution at their roots, their results have diverged in one significant way. Today, more people than ever have direct access to the text of the Bible in a language they can read for themselves. They do not have to take anyone’s word for what the Bible says. Meanwhile, we all have to take someone’s word for what the world is like in various corners. No one can make all the observations themselves, or even review the data collected when others made observations. Whereas in the days of natural philosophy, everyone could see the same sky in the same detail, or experience the same weather patterns, or interact with the same plants and animals — at least within a given community with shared knowledge.

Taking Polkinghorne’s critical realism perspective, we know more true facts about how the world works than we did 500 years ago, and we are more certain about their accuracy. Yet paradoxically, that knowledge is fractured and we find ourselves disagreeing not just about how to apply our knowledge or what values to prioritize but about the facts themselves. Communication becomes challenging because we aren’t even talking about the same world.

And so if I could nail a thesis to a door, I’d propose that the Bible is more important as science progresses, rather than less. If we can’t have scientific observations and data in common because they are too numerous and too diverse, then the Bible can provide a tractable common framework from which to operate. Of course, there is diversity of thought within the Christian community, and having the Bible in common has not eliminated all conflicts — as the Reformation era amply illustrates. Still, it seems we need something to provide a frame of reference and it’s not clear we’ve found anything better.

Andy has worn many hats in his life. He knows this is a dreadfully clichéd notion, but since it is also literally true he uses it anyway. Among his current metaphorical hats: husband of one wife, father of two teenagers, reader of science fiction and science fact, enthusiast of contemporary symphonic music, and chief science officer. Previous metaphorical hats include: comp bio postdoc, molecular biology grad student, InterVarsity chapter president (that one came with a literal hat), music store clerk, house painter, and mosquito trapper. Among his more unique literal hats: British bobby, captain’s hats (of varying levels of authenticity) of several specific vessels, a deerstalker from 221B Baker St, and a railroad engineer’s cap. His monthly Science in Review is drawn from his weekly Science Corner posts — Wednesdays, 8am (Eastern) on the Emerging Scholars Network Blog. His book Faith across the Multiverse is available from Hendrickson.

Regarding Galileo and the actions of the Catholic Church, the opposition to Galileo (and Copernicus) goes a little deeper than you might think. Charles Hummel, in his book “The Galileo Connection”, offered the idea that the opposition came, not from the church, but from entrenched academics who saw Galileo’s thoughts as threats to their position. They used the Catholic Church as a vehicle to exact punishment. This doesn’t get the Church off the hook, by any means.

Thanks for the book suggestion. Hummel’s idea certainly sounds plausible. It is consistent with the popular notion that scientific paradigm shifts are more a product of demographic shifts as the old guard is replaced by a new generation more comfortable with a new idea, and less a product of anyone being persuaded to change their perspective.

The Galileo story is certainly a complex one, and I hesitated mentioning it at all because one can quickly fall into easy narratives. At the same time, discussing the history of the Catholic Church and science felt incomplete without some nod to the topic everyone is sure to think of.