)

)We’ve been taking a look at what an evolutionary natural history implies about God’s nature, human nature, and other theological topics. Last week I addressed some of the benefits of an evolutionary perspective. I think affirming evolution doesn’t mean settling for an otherwise undesirable position out of obligation to science; I believe looking at the world through an evolutionary lens is actually consistent with the narrative of scripture. At the same time, I am a biologist and this is a science column, so I’d like to wrap up by talking a little science.

When evolution is called “settled science,” it’s easy to imagine the theory as largely in our scientific past. For many biologists, evolution is integral to their scientific present and future. Independent of natural history, we need the concepts of variation and selection to understand how antibiotics develop drug resistance, how HIV evades our immune system, how cancer develops and responds to treatment, and a whole host of health and well-being concerns. Common descent frames how we extrapolate biological knowledge of other organisms to human biology; studying gene functions in model systems has taught us much about how our own genes work. There are even applications outside of biology; for example, the techniques of phylogenetics developed to understand how DNA sequences from different organisms are related have also illuminated the relationships of different Biblical manuscripts.

At the same time, learning how evolution worked and works continues to be a productive research topic. While natural selection remains a core concept, it is also fairly broad. We For any given adaptation, we want to know the steps by which it arose, what conditions made that adaptation possible and what conditions made it necessary; variation plus selection isn’t always satisfactorily detailed. Does that mean evolution is wrong? Not necessarily. Think about the special effects in the latest blockbuster movie. If you watch the special features on the DVD to find out how they were accomplished, sometimes the answer you get is “with computers.” That’s a true answer, and for some that’s as much as they want to know. For others, it’s unsatisfying because it’s always the answer. Some people want to know the details about subsurface scattering or physically plausible shaders. For biologists, evolution or natural selection is the generic answer but there’s still plenty to learn about the specifics. I want to highlight a few of those specific directions scientists are currently exploring.

We have a pretty good understanding of how genetic changes — alterations to the sequence of one’s DNA — are inherited from our parents. But genetics don’t fully determine biology; our bodies also respond to our environment and to our choices. There is growing evidence that occasionally these responses of our bodies can also be passed down without DNA changes; this is called epigenetic inheritance. For example, we’ve observed a correlation between DDT exposure in the 1950s and current obesity rates. The particulars of which environmental responses can be inherited epigenetically are somewhat controversial, not least because there are sometimes racial implications, but we have found biological mechanisms that explain how epigenetic inheritance could happen in principle. Still, even if/when epigenetic inheritance occurs, it generally only lasts for a few generations, which raises questions about its relevance to evolution. All of this uncertainty makes epigenetics a very active area of research.

)

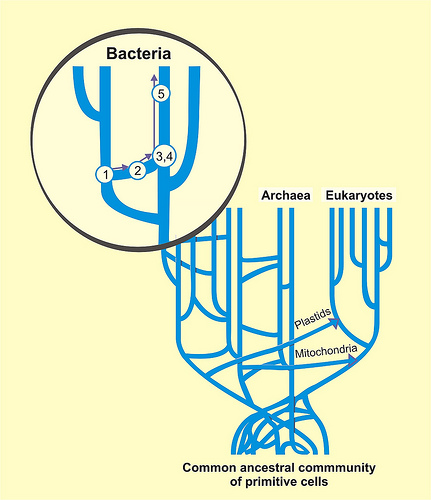

)If inheriting physiological changes from your parents sounds odd, imagine inheriting genetics from your siblings. That’s called horizontal gene transfer. Picture a family tree. Vertical gene transfer is what goes on from parent to child because those are the vertical lines in a family tree; horizontal gene transfer then involves horizontal lines, although technically it can happen between any two individuals even if they aren’t related. Horizontal gene transfer happens regularly among bacteria. They have an entire mechanism for swapping genes around between “peers.” In fact, that’s one reason antibiotic resistance spreads so quickly. Multicellular organisms like people can’t swap genes in the exact same way, but there are certain viruses that can bring genetic material from a first host along with them when they infect a second host, making horizontal transfer at least theoretically possible even for us. Deciphering when and where in evolutionary history this kind of horizontal inheritance was significant is another focus of current research.

Once you’ve inherited all those genes (and maybe epigenetic signals) from your parents, you’re still just a single cell. How does that one cell with that one genome become all the different cells that make up you? That’s the subject of developmental biology. One of the remarkable findings of developmental biology is how similar development is at the genetic level across widely different species. For example, the genes that orchestrate the development of a bird wing are very similar to the genes orchestrating development of fish fins are very similar to the genes orchestrating development of human arms. Development turns out to be very modular and extensible; there’s a basic scaffolding common across many animals and each species slots their unique particulars into it like plugins adding functionality to a web browser. The commonalities and modularity of the development processes make it easier to understand how anatomical changes can evolve.

Of course, generating and inheriting variations no matter what the mechanism is of little value if those variations just break something that was previously working. That’s where the robustness of biological systems comes in. Can organisms tolerate changes or will they be significantly disrupted by change? At least when it comes to certain key features like metabolism, the data leads us to believe biological systems can actually tolerate a fair amount of change. That’s partly due to the modular nature of chemistry; since the constituent elements of molecules can be swapped around to make new molecules, it’s possible to take a variety of different kinds of food and make the chemicals that are essential to life.

These are just some of the current fields of active research in evolutionary biology. If you’re curious, next week I’ll have some links to further reading as a way to wrap up this series. I know this has been a longer-than-normal exploration of a single topic, but evolution raises so many questions that it’s hard to cover briefly. As it is, we haven’t even surveyed the whole landscape, let alone going deep on any facet. I hope I’ve been able to advance your understanding of evolution and how it might reconcile with Christian theology; if there are more questions, feel free to share in the comments.

Andy has worn many hats in his life. He knows this is a dreadfully clichéd notion, but since it is also literally true he uses it anyway. Among his current metaphorical hats: husband of one wife, father of two teenagers, reader of science fiction and science fact, enthusiast of contemporary symphonic music, and chief science officer. Previous metaphorical hats include: comp bio postdoc, molecular biology grad student, InterVarsity chapter president (that one came with a literal hat), music store clerk, house painter, and mosquito trapper. Among his more unique literal hats: British bobby, captain’s hats (of varying levels of authenticity) of several specific vessels, a deerstalker from 221B Baker St, and a railroad engineer’s cap. His monthly Science in Review is drawn from his weekly Science Corner posts — Wednesdays, 8am (Eastern) on the Emerging Scholars Network Blog. His book Faith across the Multiverse is available from Hendrickson.

Leave a Reply