And yet, as any parent knows, this does not mean that caring for them is an equally simple task. In fact, the inverse is true; the more primitive and helpless a baby is, the more complex his or her surrounding world must become in order to support life. At this point in residency, I have watched over patients of all ages and types, and few patients in the hospital are as fragile as those in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. A single additional day of maturity, a few extra grams of weight, even the presence or absence of light can mean the difference between life, death, and permanent disability. Thousands of dollars are easily spent on the titration of medications or nutritional formula by milligrams and milliliters.

Why? Some of these extreme measures are driven by a sense of hope and potential. It reminded me of career advice from a former obstetric attending:

Say you get this interesting case in internal medicine – a 78 year old lady or something – and you work your butt off to figure out what’s wrong with her. You fix it and end up adding another two years to her life. She gets to see her grandson born, spend some time with her family, etc, etc, whatever before she dies. That’s great; you just gave her two years that she wouldn’t have had and that’s a wonderful thing. But when I get a woman in labor with a bad complication – a cord prolapse or something – and I snatch that baby out and save it. . . . I just saved 80 years of potential right there. I deliver another baby that day: 70 years . .. I’ll even take 60 years. Who knows what that kid will be some day? Maybe I just delivered a Nobel Prize winner. If you’re talking about bang for your buck, nothing can beat OB.

I have cared for healthy babies, smiling babies, beautiful babies. In them, it is easy to visualize a gloriously bright future. But I have also cared for babies born into toilets, babies screaming from drug withdrawal, babies with terminal and rapidly fatal conditions, babies with cancer, babies with brains chewed into sludge by meningitis, babies thrown across the room or strangled by abusive parents, babies with strokes, babies burned in bath water . . . the list goes on. Fundamentally, all of these babies had the same reflexes: cry, sleep, eat, poop. And yet I remember feeling differently and much more deeply for the latter cases, partly out of grief for a loss of potential but perhaps also because I witnessed in them manifestations of humanity’s wide range of vices and vicissitudes.

… He has shown strength with his arm;

he has scattered the proud in the thoughts of their hearts;

he has brought down the mighty from their thrones

and exalted those of humble estate;

he has filled the hungry with good things,

and the rich he has sent away empty.

He has helped his servant Israel,

in remembrance of his mercy,

as he spoke to our fathers,

to Abraham and to his offspring forever.– Luke 1

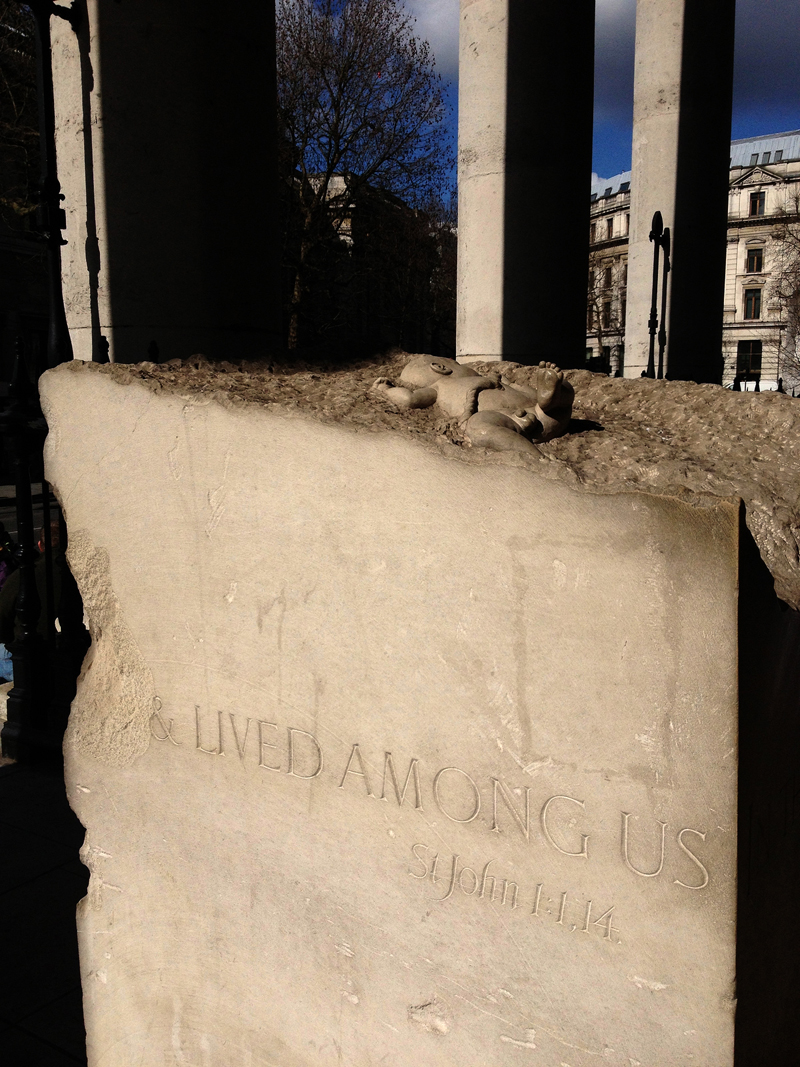

For God so loved the world, that he gave his only Son, that whoever believes in him should not perish but have eternal life. For God did not send his Son into the world to condemn the world, but in order that the world might be saved through him. Whoever believes in him is not condemned, but whoever does not believe is condemned already, because he has not believed in the name of the only Son of God. And this is the judgment: the light has come into the world, and people loved the darkness rather than the light because their works were evil. For everyone who does wicked things hates the light and does not come to the light, lest his works should be exposed. But whoever does what is true comes to the light, so that it may be clearly seen that his works have been carried out in God. – John 3

In all the pageantry and sentimentalization that has suffused Christmastime, it is easy to forget that the Word made flesh came to reveal both grace and truth. As we examine critically the true nature of our selves, let us come to Him:

Where children pure and happy pray to the blessèd Child,

Where misery cries out to Thee, Son of the mother mild;

Where charity stands watching and faith holds wide the door,

The dark night wakes, the glory breaks, and Christmas comes once more.O holy Child of Bethlehem, descend to us, we pray;

Cast out our sin, and enter in, be born in us today.

We hear the Christmas angels the great glad tidings tell;

O come to us, abide with us, our Lord Emmanuel!

David graduated from Princeton University with a degree in Electrical Engineering and received his medical degree from Rutgers – Robert Wood Johnson Medical School with a Masters in Public Health concentrated in health systems and policy. He completed a dual residency in Internal Medicine and Pediatrics at Christiana Care Health System in Delaware. He continues to work in Delaware as a dual Med-Peds hospitalist. Faith-wise, he is decidÂedly Christian, and regarding everything else he will gladly talk your ear off about health policy, the inner city, gadgets, and why Disney’s Frozen is actually a terrible movie.

Leave a Reply