Reading

Through the creatures Thou hast madeShow the brightness of Thy glory,Be eternal Truth displayedIn their substance transitory,Till green Earth and Ocean hoary,Massy rock and tender bladeTell the same unending story —“We are Truth in Form arrayed.”[….]Teach me so Thy works to readThat my faith,—new strength accruing,—May from world to world proceed,Wisdom’s fruitful search pursuing;Till, thy truth my mind imbuing,I proclaim the Eternal Creed,Oft the glorious theme renewingGod our Lord is God indeed.– from “A Student’s Evening Hymn” by James Clerk Maxwell, April 25 1853

Reflection

The rate of change of scientific hypothesis is naturally much more rapid than that of Biblical interpretations, so that if an interpretation is founded on such an hypothesis, it may help to keep the hypothesis above ground long after it ought to be buried and forgotten.At the same time I think that each individual man should do all he can to impress his own mind with the extent, the order, and the unity of the universe, and should carry these ideas with him as he reads… passages [of the Bible] (Hutchinson 1998)

Prayer

(final stanza of Maxwell’s A Student’s Evening Hymn)

Dear Lord of Light,Give me love aright to traceThine to everything created,Preaching to a ransomed raceBy Thy mercy renovated,Till with all thy fulness satedI behold thee face to faceAnd with Ardour unabatedSing the glories of thy grace.

Questions

References

- Einstein, A. Maxwell’s Influence on the Development of the Conception of Physical Reality, in “James Clerk Maxwell: A Commemorative Volume 1831-1931”, 66-73 Cambridge University Press: 1931

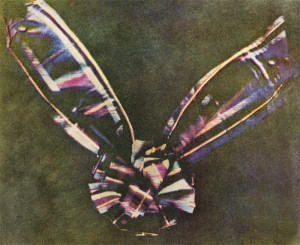

- Evans, Ralph M. “Maxwell’s Color Photograph.” Scientific American 205, 118-128 (Nov 1961)

- Hutchinson, Ian. “James Clerk Maxwell and the Christian Proposition.” MIT IAP Seminar: The Faith of Great Scientists, Jan 1998, 2006.

- Maxwell, James Clerk. “A Student’s Evening Hymn” from Campbell, Lewis; Garnet, William. The life of James Clerk Maxwell : with a selection from his correspondence and occasional writings and a sketch of his contributions to science. London : Macmillan: 1882.

Note: Originally titled The Accidental Camera and a Student’s Evening Hymn: James Clerk Maxwell on Faith and Science

J. Nathan Matias (@natematias), who recently completed a PhD at the MIT Media Lab and Center for Civic Media, researches factors that contribute to flourishing participation online, developing tested ideas for safe, fair, creative, and effective societies. Starting in September 2017, Nathan will be a post-doctoral researcher at the Princeton Center for Information Technology Policy, as well as the departments of psychology and sociology department

Nathan has a background in technology startups and charities focused on creative learning, journalism, and civic life. He was a Davies-Jackson Scholar at the University of Cambridge from 2006-2008.

Wonderful thoughts – thanks! I wholeheartedly agree with the prayers for wisdom, efficiency, and good quality sleep!

Thanks kseaton!

Maxwell accumulated a few dozen works of verse in his lifetime, demonstrating that he had successfully mastered the art of end rhyme. A Scholar’s Evening Hymn is one of his best, although the Poetry Foundation does not include it in their list of Maxwell’s poems.

A typical example can be found in his verse, “Lines written under the conviction that it is not wise to read Mathematics in November after one’s fire is out,” which I first learned about from Jeffrey Machowiak. You’ll see what I mean about rhyme:

Maxwell also loved to write scientific problems in verse, such as “A Problem in Dynamics”:

Maxwell is not alone in this wonderful precursor to Dance Your PhD. Scientific American has published a small anthology of poetry by victorian scientists, including Maxwell’s lovely “Valentine by a Telegraph Clerk (male) to a Telegraph Clerk (female).” I especially love this stanza:

Maxwell’s colleagues at Cavendish also routinely authored scientific poetry. A History of the Cavendish Laboratory remembers Cavendish alumni parties:

I received a lovely note today from Philip L. Marston, a physics professor at Washington State University, with further resources he’s written on Maxwell’s life and faith.

P. L. Marston, “Maxwell and creation: acceptance, criticism, and his anonymous publication” American Journal of Physics, 75 731-740 (2007).

James Clerk Maxwell: Perspectives on his Life and Work

Editors: Andrew Whitaker, Mark McCartney & Raymond Flood

Oxford University Press, January 2014

Chapter 14: “Maxwell, Faith and Physics”

pp. 258-291 & 339-353