Editor’s note: I had the privilege of meeting G. Randall Bond, M.D. at Urbana12. Randy was one of a number of people who visited the Emerging Scholars Network (ESN) booth to share not only a vision for, but also a commitment to next steps in “academics-as-mission.” A hearty “Thank-you!” to Randy for sharing his passion with the Emerging Scholars Network via our blog. I encourage our readers to share their thoughts/insights on the topic with Randy. He truly enjoys engaging in Transformative Conversations and I am hoping for the Emerging Scholars Network to be on the cutting edge of larger “academics-as-mission” conversations in a number of contexts in preparation for Urbana15. To God be the glory! ~ Thomas B. Grosh IV, Associate Director of ESN, editor of ESN’s blog and Facebook Wall.

————

The case for academics to consider “academics-as-mission” in sub-Saharan Africa.

The call to Christian missions in Africa in the 21st Century is quite different than even 40 years ago. The Holy Spirit is now primarily using Africans to advance Christ’s church in Africa. But our brothers and sisters are still in great need. African church leaders are asking for help in transforming their communities —through development, not charity. But development is not just about village based projects and micro-enterprise loans.

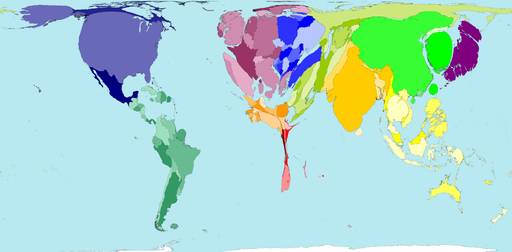

Before the turn of the 21st century university education was de-emphasized across Africa in favor of primary education. But the population of sub-Saharan Africa has almost tripled in the last 40 years. More Africans than ever are completing secondary education. The number seeking university education is up from 1% of the population in 1970 to 6% today —though this number varies country to country.

It is now understood that rapidly expanding economies also need university graduates —for government, for business and as professionals. Therefore private and public universities in Africa are starting and expanding at an incredible pace. Between 2000 and 2011 the number of institutions recognized by the Inter-University Council for East Africa almost tripled —from 33 to 87. In this context it is impossible for qualified African faculty to fill the needed teaching positions, especially in fields where advanced training has been limited, government and the private sector compete for limited talent and the “brain-drain” has taken potential faculty out of Africa. Consequently, there is great need for expatriate professors.

I believe that God’s grace to us, spiritually and materially, calls us to participate in responding to this need. One option is to get personally involved as a professor helping to educate the next generation of doctors, nurses, business leaders, entrepreneurs, engineers, architects, secondary teachers, university professors, lawyers and political leaders.

Life as an expatriate academic in Africa

Day to day, the primary role of a missionary professor in Africa is teaching undergraduates and graduate students. Additional roles include mentoring of student research projects and overseeing internship experiences. Original research and grant writing are distant “also-rans” in this hierarchy of time. Western academics also bring a different teaching model: critical thinking and reasoning skills, not just rote learning.

The case for teams

Teaching is hard enough in America but is harder in a cross-cultural environment. Not only must professors live in an unfamiliar environment (perhaps with spouses and young children also struggling to adapt), but students respond differently, the learning process is different, supporting resources are less available, the expectations of colleagues are different and things “just don’t work the same” — at the university or at home. The disorientation can be fatiguing and discouraging.

Consequently, my own bias is that in addition to institutional accountability, expatriates (and their families) serving as academic-missionaries need support and accountability to on site peers who know and understand their home culture as well as the African culture — the kind of support traditionally associated with being part of a missionary team. While one might fantasize about being a solo expatriate, serving directly under the leadership of an African institution, it is difficult to imagine working alone successfully in the African environment. Team support includes encouragement, helping to set boundaries, providing practical help with housing and “life” and providing spiritual and mission-work support/accountability. Teams also provide a context for believers to engage in repentance and reconciliation and in a way that demonstrates Christ’s glory to a watching and waiting world.

For your prayerful consideration . . .

- Are you willing to help construct an academic environment in American institutions that allows peer academics to respond to this need without making career-ending choices?

- Are you willing to consider spending a portion of your career in Africa?

- Are you financially willing to support those who may be willing to go?

For you know the grace of our Lord Jesus Christ, that though he was rich, yet for your sake he became poor, so that you through his poverty might become rich. — 2 Cor 8:9

I know that the Lord secures justice for the poor and upholds the cause of the needy. — Ps 140:12

[In the second and final installment I will discuss some models of Academic partnership in Africa and hope to learn from readers about more and highly successful models.]

Dr. Bond is currently in French language school preparing for a new role working under an American NGO providing medical education, pediatric consultation and recruiting professors for Hope Africa University in Bujumbura, Burundi. He and his wife expect to be on site in Bujumbura in early 2014.

Dr. Bond was the Medical Director of the Cincinnati Drug and Poison Information Center and Professor of Clinical Pediatrics and Emergency Medicine at the University of Cincinnati 1999-2012. Prior to this, he held the same positions at the Blue Ridge Poison Center at the University of Virginia 1989-1999

Dr. Bond completed a fellowship in Medical Toxicology at Good Samaritan Hospital/Samaritan Regional Poison Center (now Banner Samaritan) in Phoenix, Arizona. He has practiced pediatric emergency medicine and medical toxicology for over 25 years.

Dr. Bond is a past-president of the American Academy of Clinical Toxicology and a former chair of the American Board of Medical Specialties’ examination sub-board in the specialty of Medical Toxicology. He has served as an Associate Editor (for Toxicology) of the Annals of Emergency Medicine and is on the editorial board of Clinical Toxicology. Dr. Bond was awarded the 2012 Louis Roche Lecture by the European Association of Poison Centres and Clinical Toxicologists, its highest honor. His topic was the Underappreciated Problem of Pediatric Medication Errors in the Developing World.

Dr. Bond has authored more than 50 toxicology articles or chapters and delivered more than 100 major toxicology lectures in the United States and 30 around the world. His particular career interests have been in pediatric poisoning injury, acetaminophen toxicity and the epidemiology of drug abuse. He has participated in the training of more than a score of toxicology and pediatric emergency medicine fellows and innumerable residents.

Dr. Bond has long been interested in international medicine. In 1985-1986 he served as the sole doctor for a rural area of Kenya with a population of 30,000-50,000. He has lectured to physicians throughout the world. He serves on the board of World Harvest Mission, an NGO with health related work in Kenya, Uganda and South Sudan. He has assisted the World Health Organization (WHO) in developing rural triage criteria for pediatric hydrocarbon exposure and pediatric pesticide exposure. He has served the WHO as an onsite trainer of physicians and other health care workers at the site of the outbreak of severe pediatric lead poisoning in northern Nigeria. In 2012, he pioneered a long-term on-site presence for Cincinnati Children’s Hospital at Kamuzu Central Hospital in Lilongwe, Malawi. As a result, that work is funded through 2017.

Thank you so much for this post! This has been on my heart for years now, and you are the first person that I have seen make the case so clearly and straight to the heart of the matter.

I would love to hear more about your work and potential opportunities – perhaps Tom Grosh can put us in touch?

Yeah! So good to read Kelly. I’ll connect you via email 🙂

Hi Randy and everyone, I’m just pitching in as this conversation gets underway, and I’m looking forward to the next post. I’m an Australian working as a chaplain at a Tanzanian university in which a number of expats serve on staff (as is the case in universities across the country).

I wonder if I can table some initial reflections — not that your post necessarily precludes or contradicts these, Randy! These are simply some of the pressing questions from my perspective.

First, we need to critique our own expectations of “call” and service. For example, with African Christian communities thriving, we must be newly attentive to the call of the church: are African brothers and sisters prepared to accept us? And are we ourselves prepared to truly collaborate with them as full partners? In order to consider this, we must be mindful of Africa’s missionary history — have we appreciated John Gatu’s call for a moratorium on Western missionaries, for example? — and the existing landscape. This is not to say that there is automatically no place for us, but that we will only discover a legitimate place from a new stance of listening and self-criticism in light of postcolonial realities.

There are at least two things I’m getting at here: the difficulty for us Westerners to comprehend “Africa” in the first place, and the ease with which our own initiative and prerogative asserts itself. Therefore, while I agree that there is an academic need in Africa and that expats can play a part in meeting it, (1) the fact that African universities require more teachers does not itself constitute an invitation to Africa, and (2) the fact that we want to serve, and believe we can do so effectively, is no guarantee that others will be well served by us.

The situation of African universities is full of promise but also danger — it is ripe for renewed, surreptitious forms of colonialism. Gone are the days when we could perhaps think to ourselves, “I can see a need; I can serve it; therefore I will go.” Let’s pray instead, “Lord, I want to serve; help me overcome my paternalism!”

Arthur,

Thanks for your response! My intent was to bring up the issue and in part two, start a conversation on models. You have taken us further. You are right to introduce from the beginning of our discussion the question of our own hearts and our cultural “baggage”. Why would we go, can we really partner as equals, can we truly understand the culture, can we/how can we be “effective” in the big picture. Motive and methods.

You are correct that my remarks presuppose an invitation by local Africans to assist their specific efforts. That is my bias as well. Of course there is not one “African” perspective on what a partnership ought to look like. Some would welcome a form of help that others would eschew.

I particularly liked your phrase “the ease with which our own initiative and prerogative asserts itself”. We have so much initiative and, once invited, it is so easy to bring resources, even simply talent, and create dependence. I have seen that repeatedly.

As we each consider responding to invitations, we need self-awareness, situation-awareness and wisdom. I hope that you or someone else will consider writing a series for this blog on how we can examine our hearts and on the perspectives we must consider to find God honoring models of partnership. I would like to hear specific experiences of such partnerships in African universities, including yours in Tanzania. More links to resources would be helpful as well (I liked the article on John Gatu’s 1971 challenge to mission agencies). Two general audience books (not specific to academic issues) that I have found helpful are “When helping Hurts” and “African Friends and Money Matters”. Neither has all the answers and certainly I don’t.

May the Spirit give us wisdom to respond with servant hearts, as we ask Him in faith.

Thanks for your gracious response, Randall!

I write very much as a fellow traveler (we’ve scarcely lived here more than 6 months) and I’m still learning how to formulate these things as guiding questions rather than as endless qualifications — like so much dust in the air!

Or perhaps dust is part of what we need? Africa means Bad News; Africa means “They need any help they can get!” Africa being what it is to Western minds, I wonder if we need our perceptions shattered before we can renew our horizons.

As you say, the reality is a multiplicity of perspectives, and this is something difficult for us to see without a bit of coaching. For one thing — the more we talk about specific nations, people groups, regions, and communities, the better.

Answers look pretty thin on the ground to me, but more important I think is our capacity to ask fitting questions. There is a lively and growing conversation about this — something vital to participate in if we are exploring a call overseas. Here are a couple of links to that end:

• When rich Westerners don’t know they are being Rich Westerners

• Africa is a country

• My series on “vulnerable mission” (I’ll draw on these thoughts later on, perhaps)

Dear Tom,

Thank you for posting this. You’ve highlighted an important avenue of service.

However, it’s always an uphill struggle when in the US to move churches and student groups from a narrow “missions” focus (i.e, going abroad) to thinking Biblically about mission, beginning in their own backyard. Much of the scholarship that affects Africa is being done in globally influential research universities and institutions in the USA, and we need to challenge all those who care for Africa and the world to take up positions in those universities and institutions. Re-thinking mission has been my life’s work. And I wish as many American students, faculty and IVCF staffworkers as possible will read books such as Chris Wright’s “The Mission of God” (published by IVP) for such a deeper theological perspective.

So, while not wanting to detract from Randall Bond’s challenge to American students, I would like to see (for instance, at the next Urbana) a powerful call to students to move away from Christian colleges and to enter the best secular universities in the US do good scholarship that will contribute to the global common good. In that way African universities will benefit (and remember that many African scholars sojourn in these American universities as PhD students or professors on sabbatical).

Vinoth

Thanks for your thoughts! I certainly did not intend to present this as either/or issue or to limit “mission” from a broader call to life as a disciple, but to open a new career/part-career option for younger and future academics to consider, and if I am honest, for retired and near retirement academics as well. I have no regrets about my 26 years as faculty at secular universities in the US. In my view, it is a question of individual desire/calling and the possibility of opening the American academy to some career flexibility. I expect few are called to Africa, but I would love those who are to hear the challenge.

From a pediatric physician’s standpoint, the biggest impact I can imagine for Africa is an effective malaria vaccine—and that is unlikely to come from African institutions. American scholarship can make a huge impact on life in Africa, from America.