I watched the grainy, blocky video in silence. My friend was singing “Land slide” and I felt a cer tain taut ness in my eye brows and a pecu liar heavi ness in the cor ners of my mouth. By now it had become a famil iar feel ing, this phys i cal expres sion of sorrow.

Can the child within my heart rise above

Can I sail through the chang ing ocean tides

Can I han dle the sea sons of my life?”~Fleet wood Mac, “Land slide,” The Dance, 1997

Sonia Lee ’06, whose mel low and res o nant voice was cap tured in that video, passed away in 2007, during my second year of medical school. For most of our mutual friends at our college Christian fellowship, her pass ing became our first encounter with the death of a friend. In many ways, it chal lenged my most deeply held con vic tions about the way the world works. I went to med ical school with the grow ing con vic tion that my call ing was to deal with death and suf fer ing on the pro fes sional level, but this experience —so unex pected, tragic, and ter ri fy ingly personal —cast every thing under a dif fer ent pall.

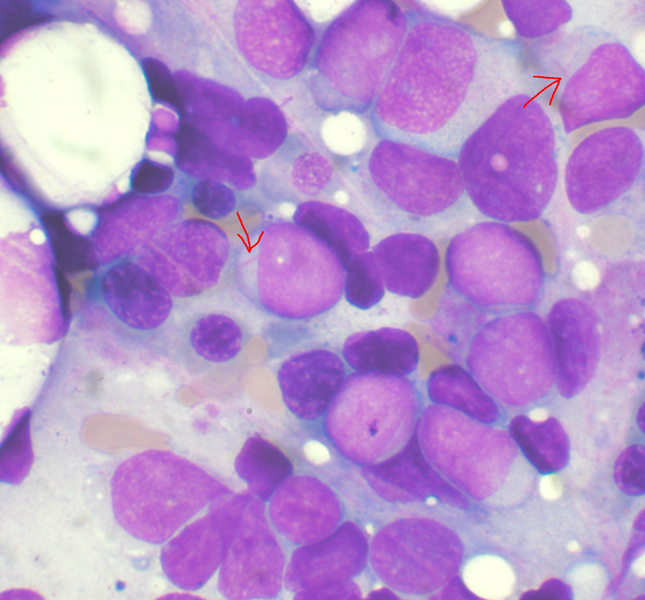

Sonia had acute myeloid leukemia. The onset was rapid and com pletely unex pected by friends and fam ily alike. I can still remem ber the dread of the moment I first found out: a string of e-mails with the titles “Urgent prayer for Sonia’” wait ing qui etly in my inbox. Sonia and I had been good friends dur ing our under grad u ate years but had fallen out of touch since my grad u a tion two years prior and I had not heard much from her since then, which made the sud den ness and feroc ity of the dis ease all the more shock ing. A full year in med ical school did noth ing to pre pare me for the daily anx i ety of open ing my e-mail in antic i pa tion of an update from the fam ily on her con di tion. I still have all those e-mails: seventy-seven mes sages with head ings rang ing from “A pos i tive turn for Sonia!” to “Sonia —Chemotherapy day 3” and “Emer gency request for platelets.”

I received those updates nearly every day for sev eral months, track ing her progress through the end of the sum mer and into the begin ning of the school year. It was a try ing time for our com mu nity of mutual col lege friends. We prayed together, planned gifts for her together, and waited together every day for those e-mails with hope and fear.

I remem ber the tight ness in my gut dur ing my first med ical lec ture on leukemia, try ing to sup press my emo tional con fu sion as the pro fes sor raced through hun dreds of slides. I remem ber lis ten ing to the com plaints of class mates about how “over whelm ing” the lec ture was and nod ding my agree ment as I headed over to a com puter clus ter, dizzy and ambiva lent and anx ious to check my e-mail. By that week Sonia had been doing much bet ter and was sim ply wait ing for a bone mar row trans plant donor. Her fam ily hadn’t been able to match but, by some mir a cle, had been able to get her story pub lished on the front page of a big South Korean news pa per ask ing peo ple to test for match ing. Her pic ture in that arti cle was the only one I saw taken of her dur ing that time and it did not show the smil ing, radi ant friend I had known.

The seventy-third e-mail on the sub ject, received only a few days later, car ried the head ing, “Bad News.” The seventy-seventh e-mail was entitled, “Memo r ial Gath er ing for Sonia K. Lee ’06.”

I often find myself dwelling frequently on that time. After those events, friends I talked to in med ical school or in church —those whom I had expected to under stand my strug gle and accom pany me through it —said that such a fix a tion on death and suf fer ing was unhealthy and perhaps even patho logic: “It’s over now; she’s in a bet ter place,” “Everything’s going to be alright,” “Life just goes on.” I couldn’t under stand why words like those hurt. They were true, but I resisted them fiercely and was even irri tated and angered by them. “There is no pur pose behind death,” one friend sim ply replied, “We just say things like that to make our selves feel better.”

On hear ing that, my ambigu ous sen ti ments and ten sions revealed them selves for what they were: fear. Crip pling, dis abling, and ter ri fy ing fear. Toni Mor ri son once said that humans react to fear by nam ing it, attempt ing to feel as if we have some under stand ing and there fore some con trol over it. We name our dis eases and our dis or ders and our bogey men. We name our fail ures and our ene mies and the secret long ings of our hearts. But in the end, a name is all we have. A name is not much.

I named my fear The Grav ity of a Moment. For me, the death of a friend is the lost oppor tu nity to sing in har mony, to shout at, to laugh with, to cry on each other. It is shock ing in its final ity and irre versibly strips my future moments of some thing pre cious, the weight of which I can not mea sure. How many more moments will lose grav ity and appear a lit tle thin ner and gaunt? Will I ever real ize the mag ni tude of what has been —and will con tinue to be —lost?

Shortly after the death, a close friend of Sonia’s told me, “I don’t under stand why peo ple didn’t want to come to the funeral or the memo r ial service ’ maybe they didn’t feel ready, but some how it feels like they’re just try ing to move on. At the funeral, her par ents told me, ‘Don’t for get her,’ but I feel like that’s what we’re doing . . . for get ting and mov ing on.” When I heard that I felt guilty because, deep down inside, I wanted to move on too but sim ply couldn’t. I wanted to find a tidy clo sure and a proper per spec tive from which to define the expe ri ence. I didn’t want to forget, but I didn’t want the remem ber ing to be so painful either.

Henri Nouwen once wrote:

We tend, how ever, to divide our past into good things to remem ber with grat i tude and painful things to accept or forget. This way of think ing, which at first glance seems quite nat ural, pre vents us from allow ing our whole past to be the source from which we live our future. It locks us into a self-involved focus on our gain or com fort. It becomes a way to cat e go rize, and in a way, con trol. Such an out look becomes another attempt to avoid fac ing our suf fer ing. Once we accept this divi sion, we develop a men tal ity in which we hope to col lect more good mem o ries than bad mem o ries, more things to be glad about than things to be resent ful about, more things to cel e brate than to com plain about.

Grat i tude in its deep est sense means to live life as a gift to be received thank fully. And true grat i tude embraces all of life: the good and the bad, the joy ful and the painful, the holy and the not-so-holy. We do this because we become aware of God’s life, God’s pres ence in the mid dle of all that happens.

Is this pos si ble in a soci ety where joy and sor row remain rad i cally sep a rated? Where com fort is some thing we not only expect, but are told to demand? Adver tise ments tell us that we can not expe ri ence joy in the midst of sad ness. “Buy this,” they say, “do that, go there, and you will have a moment of hap pi ness dur ing which you will for get your sor row.” But is it not pos si ble to embrace with grat i tude all of our life and not just the good things we like to remember?*

I write about death because it rep re sents one extreme in our human expe ri ences with suf fer ing and, for bet ter or for worse, reveals the raw power of our reac tions to pain. It exposes our ten den cies to sen ti men tal ize it, to avoid it, to explain it away, to do every thing except embrace it. We may refuse to acknowl edge suf fer ing but in doing so we elim i nate an oppor tu nity to expe ri ence the true and pierc ing pres ence of God. If we cannot expe ri ence pain, how can we under stand the com fort of heal ing? If we do not under stand death, how can we com pre hend the vic tory of res ur rec tion? And so, while we ought not to idol ize suf fer ing or inten tion ally inflict it, we can not ignore its cen tral ity in our jour neys toward the divine.

The last post of Sonia’s weblog is a quote from the movie, You’ve Got Mail: “Some times I won der about my life. I lead a small life. Well, valuable, but small. And some times I won der, do I do it because I like it, or because I haven’t been brave?” In the small ness and short ness of our mor tal ity, do we dare to embrace every moment of it? Do I have the brav ery to love each painful and plea sur able instance so bit terly inter mingled in its brief course?

I can not help but won der if some where beyond the pall the grav ity which I thought was lost has sim ply become a part of some thing greater, some thing that draws me to it a lit tle more closely and tugs at my soul a lit tle more sharply. Per haps all the moments that are torn from this life are really just being trans ported, in the twin kling of an eye, to a place where the weight of the world becomes the weight of Glory and every thing I thought I lost will be found in even greater mea sure than before.

If there is one reflex in my soul stronger than all the rest, it is the long ing for that day.

Lis ten, I tell you a mys tery: We will not all sleep, but we will all be changed– in a flash, in the twin kling of an eye, at the last trum pet. For the trum pet will sound, the dead will be raised imper ish able, and we will be changed. For the per ish able must clothe itself with the imper ish able, and the mor tal with immor tal ity. When the per ish able has been clothed with the imper ish able, and the mor tal with immor tal ity, then the say ing that is writ ten will come true: ‘Death has been swal lowed up in victory.’

‘Where, O death, is your vic tory? Where, O death, is your sting?’”

~1 Corinthi ans 15:51–55

*Nouwen, Henri. Turn ing My Mourn ing Into Danc ing: Find ing Hope in Hard Times (Nashville: W Pub lish ing Group, 2001), 17–18.

[ Orig i nally pub lished in 2008. This January marked Sonia’s 29th birth day. Happy birth day, Sonia; we miss you.]

David graduated from Princeton University with a degree in Electrical Engineering and received his medical degree from Rutgers – Robert Wood Johnson Medical School with a Masters in Public Health concentrated in health systems and policy. He completed a dual residency in Internal Medicine and Pediatrics at Christiana Care Health System in Delaware. He continues to work in Delaware as a dual Med-Peds hospitalist. Faith-wise, he is decidÂedly Christian, and regarding everything else he will gladly talk your ear off about health policy, the inner city, gadgets, and why Disney’s Frozen is actually a terrible movie.

Leave a Reply