This is Part 4 in a five-part essay series. A version of this essay was originally published online and in print as part of “Faithful Presence in the Midst of Pluralism: Three Tensions” at Ad Fontes.

In the previous essays we have considered two tensions of living with faithful Christian presence: affirmation and antithesis and engagement and distinctness. In fact, both of these tensions rest on an even more basic tension: humility and hope. Matthew Kaemingk describes Dutch Reformed theologian and statesman Abraham Kuyper’s approach to life in the midst of pluralism as “humble yet hopeful,”[1] and this description must characterize all Christians who seek to live in the world with faithful presence. We are humble because we recognize that living together in the midst of deep differences is really, really hard, and that we will often fail to do so well. Indeed, we must remain humble regarding both our own ability to live out the tensions of faithful presence, and the outcome of our efforts to do so, which ultimately rests on factors outside our control. Yet we remain hopeful about the possibility of faithful living in the context of deep pluralism, even if it ends up being messier and on a smaller scale than we might desire.

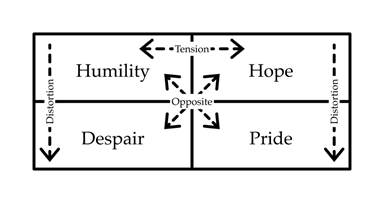

Just as with the previous two tensions, humility and hope are each subject to distortions when they cease to be held together. The distortion of hope is pride, as we forget the depth of the challenges of pluralistic living and assume that we are capable of achieving our goals easily and straightforwardly. On the other hand, when the challenges loom so large that they overshadow any possibility of hope, we abandon humility for despair.

The tension between humility and hope[2]

Kaemingk finds both humility and hope expressed in Dutch Reformed theologian Klass Schilder’s reflections on the suffering and crucifixion of Christ. When the soldiers come to arrest Jesus in the garden of Gethsemane, his disciple Peter, seeking to defend his teacher, draws a sword and cuts off the ear of a slave. Far from engaging in self-defense or even endorsing it, Jesus instead rebukes Peter and heals the slave. Following Schilder, Kaemingk sees this not as a moment of weakness but as a window into the nature of Christ’s kingly power: “Christ’s sovereign healing and power will not always take the cosmic and revolutionary scale the world so often expects or demands. The royal power of Christ’s sovereign [sic] is often limited, humble, partial, and seemingly small.”[3] From this moment of small, humble healing, Kaemingk turns to the crucifixion itself, and specifically to Jesus’ nakedness on the cross. He explains that, though respectable Christians may be scandalized by the exposure and vulnerability of one whom they revere as savior and king, his disrobing is in fact their own doing. “For in his disrobing we are fully exposed. We see ourselves for who we truly are —violent, fearful, and selfish. Beholding the naked king, we see our true nature in all its nakedness. Our pretentions of love, tolerance, and peace are laid bare.”[4] Yet this is not the end of the matter. “While Schilder’s view of human nature is dark indeed, he does not leave his readers naked and shivering in a state of total despair. In fact, it is here at the lowest point of the meditation that Schilder points to a deep hope. This hope is grounded —not in the goodness of humanity —but in the goodness of God.”[5]

This brings us to a crucial point. For Christians, the tension between humility and hope —much like the other two tensions —is resolved with reference to the divine. We are humble because of how weak and sinful humans are, yet we can be hopeful because God’s power is not limited by human weakness or sinfulness. In particular, the hope that justifies both patient engagement and active waiting is eschatological, tied to the promised return of Christ to rule as king. According to James K. A. Smith, “To worship Christ the King is to be a people with a kingdom-oriented stance, which will sometimes look aloof and will at other times pitch us into the fray. The posture of heavenly citizenship is a posture of uplift, tethered by hope to a coming King.”[6] This eschatological vision counteracts tendencies toward both pride and despair, taking a posture that is “countercultural to every political pretension that assumes either a Whiggish confidence in human ingenuity and progress or alarmist counsels of despair.”[7] It is, then, this uniquely Christian hope that equips us to live well with those who reject that very hope.

[1] Matthew Kaemingk, Christian Hospitality and Muslim Immigration in an Age of Fear (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2018), 155.

[2] Figure courtesy of Luke Herche. Used by permission.

[3] Kaemingk, Christian Hospitality and Muslim Immigration in an Age of Fear, 175.

[4] Kaemingk, Christian Hospitality and Muslim Immigration in an Age of Fear, 178.

[5] Kaemingk, Christian Hospitality and Muslim Immigration in an Age of Fear, 178.

[6] James K. A. Smith, Awaiting the King: Reforming Public Theology (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 2017), xiv.

[7] Smith, Awaiting the Kingdom, 11.

Emily G. Wenneborg is Director of Pascal Study Center and Assistant Professor at Urbana Theological Seminary. She has a PhD. in Philosophy of Education and Religious Studies from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Emily is interested in the possibilities and tensions of formation for Christian faithfulness in the midst of deep pluralism.

Leave a Reply