How does God use the migration process to extend His grace in its many forms?

I’m here at InterVarsity’s Northeast Faculty Retreat, hearing from professor Robert Chao Romero (@ProfeChaoRomero), a Chinese-Latinx American historian and immigration lawyer at UCLA. He’s the author of The Chinese in Mexico, 1882-1940 , winner of the Latin American Studies Association’s Latina/o Studies Section Book Award.

Robert opens up by pointing to I Peter 2:11-12, which argues that as followers of Jesus, we are exiles and strangers in this world. Peter urges Christians to see ourselves as “as foreigners and exiles” who are wrongly spoken of as evildoers. Consequently, immigrants teach the rest of Christianity what it is like to live as strangers in the world. Their lives and struggles are a metaphor of the Christian life. The heart of Christianity is communicated through central metaphors like marriage. When Christians mistreat immigrants and get the metaphors wrong, we obstruct our own ability to understand and experience the grace of God. Cesar Chavez argued something similar during the United Farm Workers movement, pointing out that farm workers offer important understandings about the agricultural metaphors in the teachings of Jesus.

Robert tells us about a UCLA student who recently asked him for slides from the last three classes he skipped. When Robert asked why, the student explained that his mom had been wrongly detained by ICE even though she had a green card. Because she didn’t have it on her, they detained her. It took the student four days to find her and help her get released. Similar risks are common experiences and common fears among many latinos in the US.

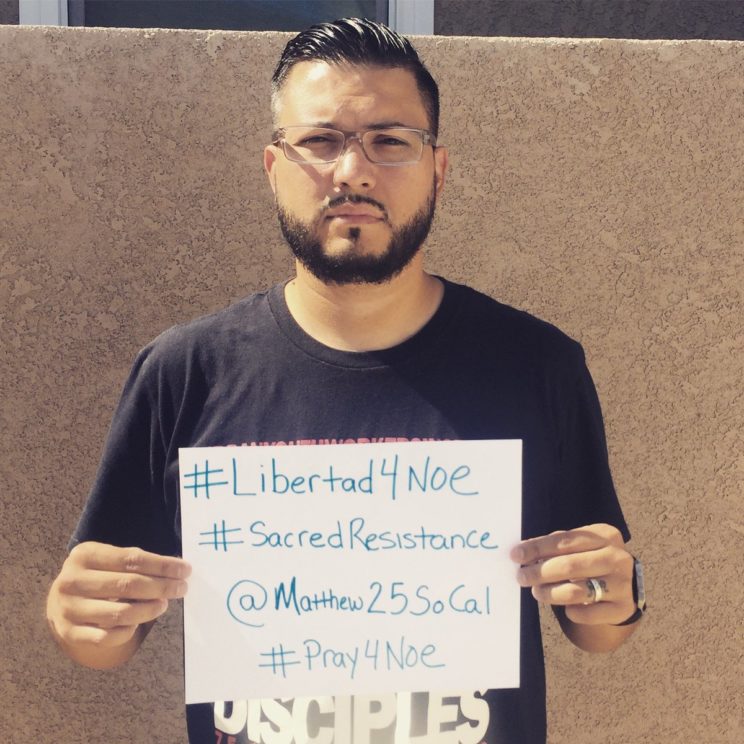

If we lived in the time of Cesar Chavez, would we be walking through the fields with him? Would we be walking with Dr. King in Selma? In the latino community, says Robert, this is one of those times: it’s a five-alarm fire right now. Friends and family are being arrested, the president keeps saying worse things. The brown church is hurting right now, and if our brothers and sisters don’t come around us, it’s going to hurt very deeply, Robert says.

Migration as a Source of Grace

How might Christians think about this moment through the lens of scripture? Robert offers a set of biblical principles that apply to the current moment. Overall, Robert argues that “Migration is a source of grace both to migrants and their host country” (journal article here). he tells us the story of his grandfather, a chinese Christian paster who was targeted to be killed by the government. He fled as a refugee to Hong Kong and Singapore and found his way to the US, through the help of powerful Christians who lobbied congress for special legislation to allow him and others to come. That saved his life. In the ministry that followed, Robert’s grandfather started seminaries in places where he fled and was eventually called the Chinese Billy Graham by Christianity Today. Many Chinese churches and denominations were started through the bridge that his grandfather was able to offer to other Chinese Christians who came to the US. In 2010, UCLA published an article about Robert’s roots and his grandfather’s founding role in 20th century Chinese Christianity.

Robert connects his grandfather’s story to the story of Abraham in Genesis, who also left his country. In the Abrahamic promise, God promised to bless Abraham and the whole world through his faithful act of migration. Robert next tells us story of Joseph, who was slave-trafficked, and who was able to bless Egypt as a government administrator because they offered him an education and an opportunity to advance in society.

Beyond individual stories, Robert reminds us that the early laws of Israel provided structural allowances for the material care of foreigners (Leviticus 23:22). He also describes civil rights protections for immigrants: “The alien living with you must be treated as one of your native-born” (Leviticus 19), “You are to have the same law for the foreigner and the native-born. I am the Lord your God” (Leviticus 24), and “Cursed is the one who perverts the justice due the stranger (immigrant), the fatherless, and widow” (Deuteronomy 27). Robert points to these passages as early examples of the ideas found in the Equal Protection Clause in the 14th amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

The Fundamental Place of Migration in Christian Teaching

Christianity is also based on migration. In Acts 17, when Paul gives a talk to the areopagus, he bases his argument about the existence for God on human migration patterns. In Matthew 25, Jesus says to his disciples that when true believers are sorted from unfaithful believers, the people who receive God’s inheritance are people who offer food, drink, clothing, medical care, and shelter to immigrants (strangers), regardless of those people’s status before the law. Jesus says, “whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did for me.” One of our barometers for our faith is how we treat the marginalized. If our hearts are hardened toward the most vulnerable in society, then our hearts are hardened to Christ.

The Bible also shares stories of “ungrace” from powerful people. In Exodus, Pharoah exhibits fearful xenophobia when he proclaims that “the Israelite people are more numerous and more powerful than we. Come, let us deal shrewdly with them, or they will increase, and in the event of war, join our enemies and fight against us… Therefore they set taskmasters over them to oppress them with forced labor.” Robert reminds us that although none of the 9/11 terrorists were latino, immigration was put under homeland security, an indicator of the fear that people have toward immigrants.

Treatment of Migrants in United States History

The US has a schizophrenic relationship with migration as grace says Robert. The United States points to the statue of liberty and welcome huddled masses- even sometimes lives out the values of that symbol. The US does receive refugees sometimes. Yet the US has often behaved differently. The first ethnic group to be singled out for migration in the US were the Chinese, extending that rule to the Asiatic Barred Zone. Next, the US restricted immigration from Italy, Jews, and others, laws that weren’t repealed until 1965. But they didn’t have enough labor, so they invited Mexicans in. When the Great Depression happened, the US carried out mass deportations. Then, when the Second World War happened, they brought back Mexicans, at least until 1954, when people were kicked out. The US tends toward these cycles that bring people of color in for work and then kick them out when they’re no longer useful or when it’s politically expedient as part of narratives of what UC Irvine professor Leo Chavez says the “latino threat.”

In the US, 11 million undocumented immigrants contribute more than 400 billion dollars per year to the GDP, says Robert. Many undocumented immigrants work with fake social security numbers. They give numbers to the employers, who set up the payment, and the US government takes 10% of the checks of millions of undocumented workers. Undocumented immigrants contributed $240 billion to the social security trust fund by 2007, saving social security. It’s in that backdrop that the US issues only 4,726 unskilled worker visas across all countries in 2010. Although undocumented immigrants already participate as economic citizens of the nation, paying into US government programs, they have not been granted the rights of political citizenship.

Why don’t undocumented immigrants just get into the line to join the country? Robert reminds us that the rules are completely impractical. For example, if someone is married to a US citizen, they are eligible for a green card, but they would have to move to Mexico for ten years before they would be allowed to be eligible. Imagine someone who’s been working in construction for 20 years, and their child is a US citizen. Technically, they can get citizenship through their child, but because that 10 year bar, they would have have to live abroad for ten years before they were eligible. The US has also been inequitable in the countries that it grants asylum to people, preferring to offer asylum to white Cubans or white Russians rather than black Haitians or brown Guatemalans fleeing civil war.

The past administration, which was no friend to immigrants, at least in theory had a prioritization for who would be targeted, focusing on people with serious criminal offenses. Now under the new policy, if you’re undocumented, the prioritization has been removed, and anyone is theoretically a target. ICE used not to take people from schools, hospitals, or churches. Now, on mother’s day, ICE swept a church parking lot to pick people up. ICE is now going to hospitals and taking people out and picking them up from schools.

Relating to Authority as Christians

Aren’t Christians expected to submit to authorities and the rule of law? Robert points to I Peter 2, where Christians are called to submit to every human authority. That’s true, he acknowledges. At the same time, we have 17 books of the Old Testament in which the prophets challenge unjust governmental leaders and societies, often calling out leaders for exploiting immigrants and the poor. Jesus brings that tradition to its culmination. As St Augustine wrote, “An unjust law is no law at all.” When laws are unjust, Christians have the obligation to challenge those laws, using the tools of loving enemies, blessing those who curse us, and accepting the consequences of resisting injustice with love. Right now in Los Angeles, Christians are sending messages with scripture and Christian social teaching to the head of ICE as they challenge these injustices. As they work to defend people from unjust deportation, Robert says, they sometimes risk imprisonment. And as Christians, Robert and others have worked to express love for the people who arrest them, which does occasionally happen.

At this point, the group concludes with questions for reflection and discussion:

- How have you, your family, or someone you know, experienced God’s grace through the migration experience?

- Have you ever witnessed unbiblical discrimination against immigrants or refugees

- How might God be calling you or your church to show his love to immigrants in your local community?

J. Nathan Matias (@natematias), who recently completed a PhD at the MIT Media Lab and Center for Civic Media, researches factors that contribute to flourishing participation online, developing tested ideas for safe, fair, creative, and effective societies. Starting in September 2017, Nathan will be a post-doctoral researcher at the Princeton Center for Information Technology Policy, as well as the departments of psychology and sociology department

Nathan has a background in technology startups and charities focused on creative learning, journalism, and civic life. He was a Davies-Jackson Scholar at the University of Cambridge from 2006-2008.

Leave a Reply