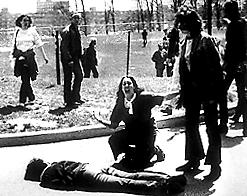

We are both “internal processors” of emotion, so we took a break partway through to get some coffee and decompress. Sitting quietly in the cafeteria, we talked absently about the photographs. “It reminded me of Ecclesiastes,” she said, and I thought about all the futility and sorrow and frustration encompassed in that book:

Again I saw all the oppressions that are done under the sun. And behold, the tears of the oppressed, and they had no one to comfort them! On the side of their oppressors there was power, and there was no one to comfort them. And I thought the dead who are already dead more fortunate than the living who are still alive. But better than both is he who has not yet been and has not seen the evil deeds that are done under the sun. – Ecclesiastes 4

New Years is usually the time in which we stop to remember major events and milestones. It is often said that “those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it,” but is the act of remembering really that helpful? The rallying cry in a post-Holocaust world has been “Never forget,” but as my brief trip down the world’s memory lane reminded me, such retention does not necessarily beget a just and civil society. Though memory can serve as a sober reminder and ward against injustice, it also has a way of twisting over time, warping the narratives of our lifetime experiences in ways that promote vengeance and actually perpetuate injustice. We can all think of traumatic events in our personal lives that have degenerated into bitterness and spite over time; how much more has this been possible in the national or international consciousness, in Kosovo and Syria and Afghanistan and the Congo and Palestine?

Miroslav Volf takes a surprising and arresting approach to these questions in his book, The End of Memory. He begins with a vivid and harrowing experience: his own unjustified interrogation by a military general. The experience leaves Volf with mental scars and he accurately notes that to remember is an act that relives the trauma, often in ways that are not positive or encouraging. But he also notes that, if we are exacting in the methodology of remembering rightly, it can offer the possibility of redemption. If we remember history rightly, we remember that Jesus Christ suffered the atonement for all our sins and crimes, that no person or nation stands otherwise justified before his throne. We can then choose not to act in retribution, and in so doing to “forget” the transgression. In this way, both victim and perpetrator freed through this act of “forgetting” are liberated from cycles of vengeance even as their injuries remain fully acknowledged. Such remembering and forgetting does not mean that the hurt of such actions is erased from our consciousness so much as it means that it no longer has power over us. This is perhaps what Scripture means when it says that God forgets our sins:

For this is the covenant that I will make with the house of Israel

after those days, declares the Lord:

I will put my laws into their minds,

and write them on their hearts,

and I will be their God,

and they shall be my people.

And they shall not teach, each one his neighbor

and each one his brother, saying, ‘Know the Lord,’

for they shall all know me,

from the least of them to the greatest.

For I will be merciful toward their iniquities,

and I will remember their sins no more. – Hebrews 8

Remember also your Creator in the days of your youth, before the evil days come and the years draw near of which you will say, “I have no pleasure in them”; before the sun and the light and the moon and the stars are darkened and the clouds return after the rain, in the day when the keepers of the house tremble, and the strong men are bent, and the grinders cease because they are few, and those who look through the windows are dimmed, and the doors on the street are shut —when the sound of the grinding is low, and one rises up at the sound of a bird, and all the daughters of song are brought low —they are afraid also of what is high, and terrors are in the way; the almond tree blossoms, the grasshopper drags itself along, and desire fails, because man is going to his eternal home, and the mourners go about the streets —before the silver cord is snapped, or the golden bowl is broken, or the pitcher is shattered at the fountain, or the wheel broken at the cistern, and the dust returns to the earth as it was, and the spirit returns to God who gave it. – Ecclesiastes 12

David graduated from Princeton University with a degree in Electrical Engineering and received his medical degree from Rutgers – Robert Wood Johnson Medical School with a Masters in Public Health concentrated in health systems and policy. He completed a dual residency in Internal Medicine and Pediatrics at Christiana Care Health System in Delaware. He continues to work in Delaware as a dual Med-Peds hospitalist. Faith-wise, he is decidÂedly Christian, and regarding everything else he will gladly talk your ear off about health policy, the inner city, gadgets, and why Disney’s Frozen is actually a terrible movie.

Leave a Reply