Summer had finally emerged and we were sitting out on my front steps, enjoying the afternoon heat and watching some of the other kids play out on the street. Some of the teenagers were casually tossing a football around, throwing it high and watching it bounce among the electrical wires, tree branches, and car windows before skittering along the pavement to be chased endlessly by the smaller children. Others were riding their bicycles for show, popping up the front wheel as they furiously pumped their pedals to maintain balance. It was idyllically urban, and I was thoroughly enjoying the leisurely scene after a month of long and hectic hours working at the hospital.

“Your parents must be rich, right?” It was an odd, abrupt question, and I pulled my eyes away from the street to take a moment and try to understand exactly what had just been asked. The twelve-year-old sitting next to me looked my way, waiting for a response. I stalled.

“What?”

“Your parents, they must be rich right?” If there was any ambiguity in the question, he eliminated it. “For you to go to medical school. Your parents must be rich, right?”

It was not the first time we had talked about money. He lived down the block, and though we had come to be good neighbors and friends over the past year, he would say things that had a similarly peculiar way of making me fumble for words. Before, they had been questions or comments like, “Why would you want to live here?” or “I know a doctor makes bank; you must be making bank” One eight-year old quipped to me, “Nobody wants to move into the North side.” When I first heard it, I thought it was sad and troubling that a child could grow up knowing that his neighbors lived there out of obligation instead of choice. When I hear it now, I still think that.

But this question had a different flavor to it. “Why do you have to be rich to become a doctor?” I asked.

“Cause, school is expensive. So you need to have a lot of money to be able to get there, right?”

“Well . . . you have to borrow a lot, and then pay it back.” That answer didn’t sit well with me, so I tried to explain. “I mean, isn’t that why doctor’s make money? Cause they’re in debt, and they need to pay it back?” That answer wasn’t any better, so I shut up.

“Whatever. Doctors make bank.” He couldn’t be shaken from this thought. Neither could I.

There is a popular article circulating among my colleagues describing the deceptive income of physicians. It is a very detailed analysis of how the economic principle of opportunity cost means that the high debt burden, long training program, and loss of financially lucrative career alternatives make a medical degree something less than a cash cow. As each of these factors augment, the ability to maintain the quality of life that physicians (and perhaps twelve-year-olds in my neighborhood) have become accustomed to is now threatened. In fact, it is part of the reason that even within the physician field, medical students are driven towards high-wage, procedure-driven subspecialties: to make up for loss in real wage with higher-value training and marketability.

However, even that has not changed the unsettling sociodemographic that dominates higher medical education: children of upper-middle income brackets. My neighbor was right; according to the Association of American Medical Colleges:

Most medical students are children of parents with high levels of education. For example, roughly one-half of medical students’ fathers have a graduate degree compared with 12 percent of the weighted sample of men in the U.S. population. Similarly, roughly one-third of medical students’ mothers have a graduate degree compared with roughly 10 percent of U.S. women.

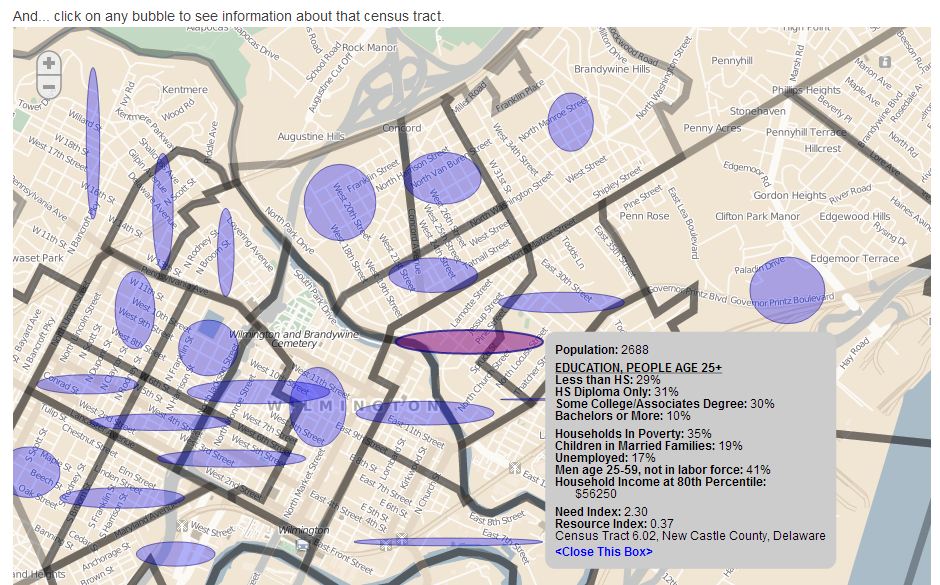

(Unsurprisingly, the disparity also carries itself along racial lines.) My father has a PhD and my mother a nursing degree, and both my siblings also went to college. This stands in sharp contrast to the neighborhood I live in now, where, according to the US Census Bureau, only 10% of the population has a Bachelor’s degree or higher, and the top 20% income bracket begins at $56,250 (which is almost exactly my salary as a resident).

That said, the first thing my parents said when visiting my neighborhood was, “This is so much like the place we grew up in!” They grew up in impoverished neighborhoods as children and even as graduate students that struggled to raise young children, as did many of their friends who similarly have graduate degrees and have sent their children to higher education as well. There was a time when something as simple as eating at McDonald’s was considered a luxury to our family, and I vaguely remember those days in my younger childhood.

I tried explaining this to my neighbor, that to answer his question, my parents did not grow up rich at all. He couldn’t believe it.

“You’re lying,” he said, over and over again. After a while, the words stung and I gave up trying to explain myself or my family. He had met my parents before, knew that they were humble and generous people, and didn’t make any other references to money or what he considered extravagant living except our education. He plans to go to college himself some day, and knowing the confidence and sharpness of his observations, I have no doubt about it.

But still, I sat there in the summer heat feeling decidedly uneasy, my leisurely sentiments having suddenly evaporated. I glanced at the thin and precise scars on his skin that were the hallmarks of a surgeon’s skill, and I wondered at exactly how our lives had come to be shaped by the practice of medicine . . . and how we, in one way or another, were the shape of its future.

What are your thoughts on the cost of higher education?

David graduated from Princeton University with a degree in Electrical Engineering and received his medical degree from Rutgers – Robert Wood Johnson Medical School with a Masters in Public Health concentrated in health systems and policy. He completed a dual residency in Internal Medicine and Pediatrics at Christiana Care Health System in Delaware. He continues to work in Delaware as a dual Med-Peds hospitalist. Faith-wise, he is decidÂedly Christian, and regarding everything else he will gladly talk your ear off about health policy, the inner city, gadgets, and why Disney’s Frozen is actually a terrible movie.

Leave a Reply