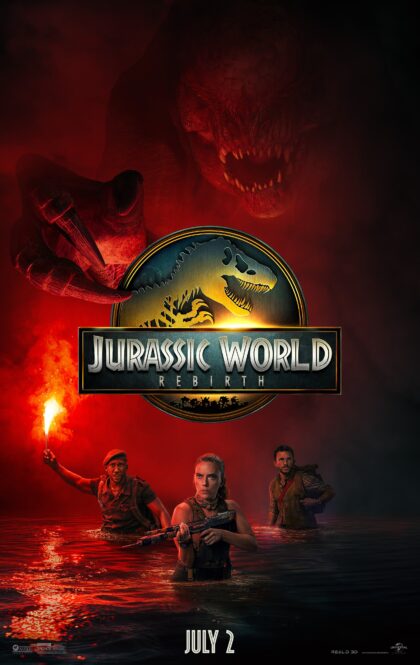

In order to explore the ideas of Jurassic Park Rebirth, this post contains spoilers for the film.

Jurassic World Rebirth, the latest film to spin out of Michael Crichton’s novel Jurassic Park, opens with a flashback revealing experiments to create mutant species of dinosaurs which never existed. We are clearly meant to be unsettled, if not outright horrified, by this revelation even before it is underlined by the death of a scientist or technician at the claws of one such creature. (In what I hope is a nod to the chaos theory at the heart of the original novel and film, this death is the result of a cascading series of events triggered by a seemingly insignificant act; or maybe it is just a sequence that got lost on the way to a Final Destination film.) And yet, not for the last time in the film, the biologist in me wasn’t entirely convinced.

Just within the story world, we are already well-acquainted with dinosaur hybrids. As Mr. DNA so helpfully explained to us, the dinosaurs in the original theme park included DNA from other species to fill in gaps where the prehistoric amber had proven an imperfect preservative. Perhaps I was hoodwinked by the charming cartoon presentation, but I took this to be a morally neutral wrinkle; the central dilemma was whether it was right to bring back dinosaurs at all. The later Jurassic World films remind us of the hybrid nature of the theme park attractions and show attempts to push the idea further to maintain cultural relevance (a variation on the Red Queen hypothesis, and potentially also a commentary on the constant struggle for our attention with the social media and smartphone app ecosystem). At that point, there was already a sense corporate greed had taken things too far, so I’m not sure what was new here for the franchise.

Stepping outside the story, I have difficulty accepting that recombining and hybridizing DNA is, on its face, taboo. I suppose the biggest concern is that the end result is unknown and unknowable. But every birth involving multiple parents is an exercise in DNA recombination and an exploration of uncharted genomic territory. And even hybrids across species can occur. Granted, typically much smaller steps are taken than those depicted in the film, but that is a matter of degree rather than kind. And that’s really more a function of the exaggerated reality of the sci-fi storytelling; in our world, there would be no reason to expect crosses of such widely diverged species would produce anything remotely viable, let alone the types of dinosaurs we are shown. For example, given how conserved the tetrapod body plan and underlying development genetics are, there is little reason to think you could get six-limbed creatures from any combination of dinosaur species. This is story logic, not biologic.

Consider also how the story itself is crafted. There are the expected homages to visuals and sequences from previous Jurassic films–a fluttering banner, an “Objects in mirror” gag, a raptor pack–while Alexandre Desplat weaves the familiar John Williams themes into his score. But there is also a boat sequence with Jaws vibes, and a young kid leading a cute “alien” around with candy. This is artistic recombination, and it is a key feature of the creative process. Crichton’s novel employs a similar technique, only mixing in elements from science fact, as all great science fiction does. That influx of ideas from outside of fiction is necessary to keep things fresh; when movies only remix other movies, eventually one gets a sense of staleness. There can also be truly original innovations as well, but we can’t ignore the value of rearranging existing story elements. When done well–and I think Gareth Edwards, David Koepp and team are largely successful here–recognizing the connections to what came before is satisfying.

While the film didn’t sell me on genetic experimentation as fundamentally a Bad Idea, it also failed to incorporate it thematically. When the villains of previous films were stymied or stomped, it was typically the result of either the hubris of believing they could control the uncontrollable or the exploitation of dinosaurs for economic or military gain (or both). They wronged the dinosaurs, and the dinosaurs wronged them back. Based on the way this story treats pharmaceutical rep Martin Krebs, there seems little doubt we are meant to understand he is the Bad Guy. We are introduced to him via the aforementioned mirror gag, suggesting we should be just as scared of him as the T Rex. And while the series as a whole has featured dinosaurs eating characters without onscreen sins, this film’s deaths feel largely karmic, highlighted by the contrapositive of a character avoiding dino-death apparently by virtue of nothing other than his, well, virtue. So when Krebs is consumed, it feels as though judgement has been passed.

But he has nothing to do with the experiments in the prologue. While assembling the cast of the film, he explains that his goal is to get samples of DNA from the largest dinosaurs because the scientists at the company he represents have determined they will contain a key ingredient to a revolutionary heart disease drug–an ingredient which cannot be synthesized, hence the need for a biological source. His plan involves extracting fairly small blood samples; by relative volume, somewhere in between the pricks used for some blood sugar or iron tests and a single test tube. Given the way the film was twirling his mustache, I kept waiting for him to reveal something more sinister. But nope, that’s it, that’s the plan–just humanely extract a little bit of blood to treat heart disease. He isn’t cruel to the dinosaurs; at worst, he is just not that into them. Instead, his sin is indifference verging into hostility towards a family of innocent bystanders who get caught up in his mission. As a result of how he treats them, his fate feels deserved–but there’s no reason it has to come at the fangs of a mutant dinosaur.

Could big dinosaurs (or big living animals) actually cure heart disease? Probably not, although I think I know where they are coming from. At the level of species, larger animals tend to have longer lifespans, which of course means that their hearts last longer. But larger animals also have slower metabolisms and hearts that beat less often, and it actually works out that these two trends balance so that many animals wind up having roughly the same total number of heartbeats in their lifetime. So there may not actually be anything more durable about the heart of Titanosaurs. Or it may be that a whole suite of complementary adaptations enable larger size and longer lifespans, rather than a single compound that could be used therapeutically. Still, I believe that is the kernel of real science driving this fiction; you can read more about that science in Scale by Geoffrey West, or listen to any of a number of podcast interviews he has done on the topic (e.g. this episode of Complexity).

Now, the operators he hires for the mission act as if he and his company are up to something more nefarious. They assume the resulting heart medicine will be priced to keep it out of the hands of the many. And sure, there are real examples of pharmaceutical companies charging prices that are difficult to explain if they are acting in good faith or as stewards of a public good. At the same time, affordable and widely available drugs do exist, so it’s not clear to me that price gauging will be a given. But that assumption is used to justify trying to keep the collected samples away from Krebs, which is treated as a heroic and altruistic decision. It’s a classic Robin Hood move–only within the logic of the story, it’s not clear what the common folk will do with their bounty. In the opening exposition, it seemed like the dino samples would factor into the production of a drug, rather than providing the drug directly. Will anyone be able to make use of them without the preliminary research of the pharmaceutical company? They merry mercs certainly have no reason to think the answer is yes. But we are swept along because the shape of the story is familiar enough; if the thematic remixing brought in a few extra limbs, who are we to quibble?

Andy has worn many hats in his life. He knows this is a dreadfully clichéd notion, but since it is also literally true he uses it anyway. Among his current metaphorical hats: husband of one wife, father of two teenagers, reader of science fiction and science fact, enthusiast of contemporary symphonic music, and chief science officer. Previous metaphorical hats include: comp bio postdoc, molecular biology grad student, InterVarsity chapter president (that one came with a literal hat), music store clerk, house painter, and mosquito trapper. Among his more unique literal hats: British bobby, captain’s hats (of varying levels of authenticity) of several specific vessels, a deerstalker from 221B Baker St, and a railroad engineer’s cap. His monthly Science in Review is drawn from his weekly Science Corner posts — Wednesdays, 8am (Eastern) on the Emerging Scholars Network Blog. His book Faith across the Multiverse is available from Hendrickson.

Leave a Reply