[Marcus Vincius De Matos, a lecturer in Public Law at Brunel University London and Board Member of ABUB (IFES-Brazil), graciously shared this article with ESN, concurrently published with Red Letter Christians]

In this piece I reflect on the 75th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and conflicting notions of Christian Theology that have recently threatened it

Human Rights are perhaps the most powerful discourse that emerged in the 20th century. No other narrative has so disturbed the world order, at least since 1848. And this political prominence is perhaps one of the main reasons why religion and Human Rights “do not mix very easily,”[1] why Human Rights so often clash with religious narratives and traditions. Human Rights have paved the way to overthrown totalitarian and authoritarian regimes worldwide, including in my own country.[2] Because of Human Rights we have seen police authorities and violent bureaucrats go to jail, and we have seen presidents and generals sentenced by international courts. The fact that Human Rights discourse has also been used to justify military interventions disguised as humanitarian actions[3] does not diminish its importance – it is actually evidence that even those who violate Human Rights recognise their power in contemporary politics.

Imagine having rights that were not determined by any moral or political choice, nor limited by any action you could take. Imagine if just by being human, belonging to the human species, you could have unalienable rights, that could not be taken away from you by any decision of any individual, institution, or state. When this idea was first created it was revolutionary. This idea attached the notion of rights to a particular ethics of human dignity. The emergence of Human Rights made it impossible to diminish people’s value to that of property – or to those animals who were poorly treated by their owners. To make my point clear, I will do what lawyers usually do: I will look into three cases that help us weave the thread of Human Rights.

In late 19th century England a woman sent an anonymous letter to Parliament requesting the approval of a bill that would allow women to be treated the same way as dogs. She explained the issue: a husband had beaten his wife to death and, because of legislation and common law at the time, he was considered as exercising the defence of his honour, his Patria Potestas. As a result, he was not sentenced. She eloquently argued that if he had brutally killed his dog he would, at least, have been fined.

In the 1960s, in Brazil, a Catholic and conservative lawyer named Sobral Pinto walked to a Brazilian Army Barracks in Rio de Janeiro, to meet his client. At his arrival he found the young student to be sleeping over his own blood and bodily fluids, in a cell without a toilet. His body showed several marks of torture. Mr Pinto decided, then, to file a complain to the Courts, requesting the Statute of Animal Rights to be applied to his client.

In the beginning of the 21st century, in Guantanamo Bay, a lawyer met the General of the US Army in charge of that detention facility. He asked the General if the Constitution of the USA would apply to his client. The General denied it. Then he asked if the Constitution of Spain would apply to his client. That was also denied. What about the Constitution of Cuba, he then asked. Finally, he asked the General about a particular species of lizard that lived in Guantanamo Bay and was threatened with extinction, and if American military personal were taking all due care to protect that species of animal according to international obligations.

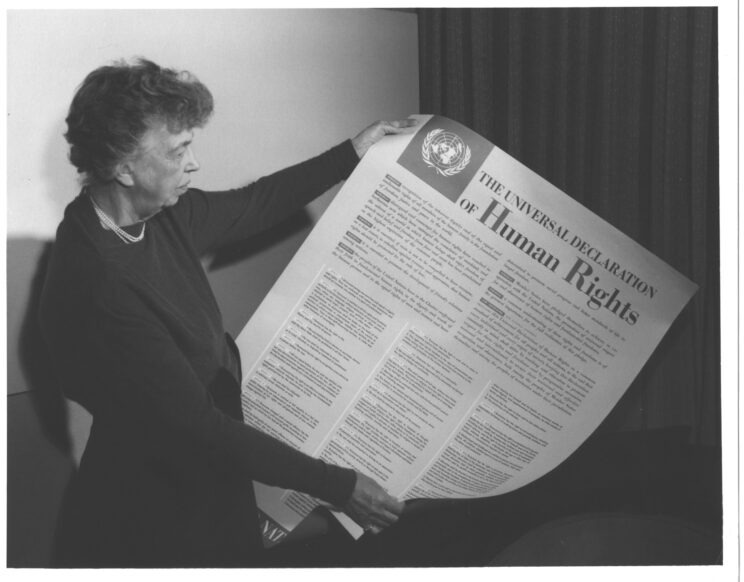

What these three cases have in common is revealing what happens in the absence of Human Rights, when people are brutalized in ways worse than animals would be. The 75th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), celebrated last month, reminds us of a document that challenged this kind of infamy. But the event was largely ignored in Christian circles, with few exceptions. In the next section I will share a few academic reflections about the importance of the UDHR, and later about its close (and now problematic) relationship with Christianity.

The state of the art of the UDHR: global perspectives and legal paradoxes[4]

I have been privileged to work with some of the greatest minds and practitioners in International Human Rights Law. To celebrate the 75th anniversary of the UDHR, I had the opportunity to jointly organise an event and hear from three Professors in my own university: Alexandra Xanthaki, Javaid Rehman and Manisuli Ssenyonjo. Some of the ideas I am about to discuss here are owed to them, who spoke about the historical and political importance of the UDHR without losing sight of the troublesome times we are currently living in – with ongoing wars in Ukraine and Gaza.

Professor Javaid Rehman reminded us of the political and international context where the UDHR was discussed, drafted and agreed. Never before or after it a document with so many rights was signed by so many states. This was no small achievement, and one reason why we need to celebrate it. According to Javaid, there is poetry in the UDHR articles and this poetics reflects a specific moment in history, the aftermath of the Second World War (WW2). The Allied nations won that terrible war and decided to advance ideas and measures that could possibly prevent new violations of Human Rights, help keep peace and build up a new international order. However, Professor Rehman also reminded us what was left out and what has changed since then. The absence of the Right to Self-determination is probably the biggest gap in the Declaration – and reveals the building up tensions between colonized and coloniser of the time. And many states have completely changed their position since they signed the Declaration. It is the case of Iran and Afghanistan, who subscribed to its article 2 opposing distinction of “any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion,” but now promote what could be called a gender apartheid against woman and girls.

Nevertheless, the two biggest issues that undermine the UDHR are its lack of operationality in the International Law system and the absence of social and collective rights in its text, according to the UN Special Rapporteur for Cultural Rights, Professor Alexandra Xanthaki. These problems continuously haunt the Declaration and are currently explored by politicians who work to undermine the United Nations authority and Human Rights. Xanthaki pointed out to the democratic challenges we currently face when a significant number of UN member states are now represented by nationalist and xenophobic politicians. But she also adopted a strategic optimism when looking into new generations. According to her, people now seem to be much more inclusive and sensible to minority rights than in any generation before – such as to care and promote LGBTQ+ rights.

The paradox of the UDHR ineffectiveness rests in its Article 28, according to Professor Manisuli Ssenyonjo: “Everyone is entitled to a social and international order in which the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration can be fully realized.” In this article the UDHR turns its own efficacy and implementation in a Human Right. However, the entitlement to a social and international order that does not (yet) exists – and may never exist – constitutes an insolvable problem. Professor Ssenyojo asked: “Has article 28 ever been respected by the signatory states in these 75 years since the Declaration?” He then pointed out to the heart of this paradox: the fact that there is no International Human Rights Court in the UN system, no international body capable of adjudication on Human Rights violations by member states. This would make the UDHR a kind of Constitution without a constitutional court, and make it impossible to impose measures to guarantee peace, prevention of violations and sanctions against state perpetrators.

But I wonder if this paradox is not the result of previous conceptual problems in the very way Human Rights have been originally conceived. How much of the notions of humanity, universalism and natural law are still alive in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights? Perhaps looking at the mobilization of Theology in Human Rights discourse by religious leaders and political organisations might explain some of these problems.

Human Rights, Natural Law and Theology

There is no doubt that Human Rights are a direct descendant from Natural Rights. What is disputed, however, is how deep our current ideas and legal documents were shaped by the re-emergence of Natural Law in the context where the UDHR was drafted. The return of Natural Law in the aftermath of WW2 has often been dismissed as either completely incorporated into Human Rights or as a strategy to blame atrocities on Legal Positivism and free the German Judiciary from the hook – such as in Radbruch’s formula.[5] I want to claim that Human Rights were not only influenced by Natural Law tradition on its later and Enlightened form, but also developed from two theological concepts linked to the idea of Justice.[6] I believe Human Rights, in the form they were given in the UDHR, are deeply connected to the theological notions of Grace and Imago Dei in Christian theology.

The universality of Universalism can certainly be put into question when it is used as a power tool to exclude others – and becomes a “bully.”[7] But the idea of Human Rights as an unconditional defence of human beings has a lot in common with the unconditional love of God in Christian theology. In Christianity there is an idea that the love of God for humans is undeserved by peoples and individuals. God would love human beings not for their merits, but by their likeness – their divine image which resembles the image of God the creator.[8] The Christian God’s love for humanity is based on grace rather than merit, it is unlimited and able to forgive any kinds of sins. This all-inclusive and unlimited love in Christian theology sounds a lot like the idea of universal “inalienable rights of all members of the human family” in the first two sentences of the Preamble of the UDHR – which are perhaps the first secularised version of this universal inclusion.[9]

This is relevant for a series of reasons, but perhaps mostly to rebuke a common question that has repetitively been raised by nationalists and religious conservative groups alike: are human rights only available to defend criminals? I have heard this question so many times in Evangelical circles. Of course, the answer is always a resounding ‘no,’ but what I have found more interesting in my research on Human Rights and Religion is that this kind of question – which wants to exclude some people from grace or mercy – also has a precedent, a fossil theological form.

I refer here to the discussions between Jesus and the religious leaders of his time, where these leaders constantly questioned Jesus on why he was always sitting and associating with sinners and gentiles. Jesus’ precise answer in Mark 2:17 also works for justifying the universality of Human Rights: it is the sick who need the doctors, not the healthy. I believe a similar argument could be applied to the universality of Human Rights to answer this insincere question: it is those who committed crimes and will be punished by the state who need their Human Rights most. The ground level of Human Rights is, then, to guarantee the humanity of the worst human beings. If this is achieved, we might believe that Human Rights apply to all human beings.

It is, after all, those in prison who are most frequently subjected to violation of their basic rights – such as in suffering abuse, torture and rape in detention facilities. It is to stop the violation of these arrested bodies – also made in the image of God, one could argue – that Human Rights prohibit the use of torture. And here we have another intersection between Christian Theology and Human Rights: torture itself can be understood as the unlimited exercise of power over the human body and its (Western) paradigmatic case is the Passion and Crucifixion of Christ.[10] This is the brutal theological meaning of Human Rights, which restricts the use of power over the bodies of those considered as the worse human beings – such as those condemned to crucifixion. This points to the minimal standard of Human Rights, proclaimed in UDHR to protect those bodies, which should be followed by every state authority.

The last 10 years have revealed a significant division among Christian organisations and individuals regarding the ethical values of Human Rights, as a concept, and the legal documents and international organisations that grant those rights – such as the UDHR and the United Nations. We have seen Christians supporting violations of Human Rights against minorities, promoting gun ownership and violence and denying the historicity of genocides. In extreme cases, Christian leaders and institutions have supported politicians who declared Human Rights to be the “manure of vagabonds”[11] and who forcedly separated children from their families – such as happened both in the USA, under the Trump administration; and in Ukraine, which led the International Criminal Court to issue warrants of arrest for Putin. These positions were, nevertheless, challenged by both Christian and secular institutions, either by their radical example[12], public statements[13] or legal proceedings.[14]

But there are at least two different kinds of criticism that can be laid upon Human Rights, as a concept, and the UDHR, as a legal document. One is criticism of exclusionary nature and the other a critique that demands inclusion. And I believe we should all stand for the later – which we shall turn to now.

Conclusion, inclusion and exclusion

The first criticism against Human Rights that is most common to find circulating online these days, derives from ethical values that were excluded from the public sphere after the WWII, by the member-states of the (then) emerging United Nations. The criticism I refer to is often an echo of ideological discourse produced by the Axis countries before that time. The values that inform these positions today are heavily based on racism, sexism, ethnic and religious discrimination such as anti-Semitism and islamophobia, and all sorts of prejudice against migrants and minorities. These are the very opposite of what one finds in the preamble and the 30 articles of the UDHR.

On the other hand, the relevant criticism that we need to consider here is the struggle for inclusion and expansion of more people, rights and values than what is originally stated in the UDHR. This is the critique that denounces the use of Human Rights for protecting economic interests and masquerading wars as humanitarian intervention – or justifying military invasions as preventive, self-defensive acts. This happens every time powerful and rich states make use of Human Rights to impose their own legislation and political power over Global South countries, disrespecting the right to self-determination – something that was not included in the UDHR, but more recently recognized as “integral to basic Human Rights, fundamental freedoms.”[15] The idea that Human Rights should include promotion of social justice, social rights and food security also falls into this category of critique.

I believe this second kind of critique to Human Rights, which includes more people in the hall of humanity, is also more consistent with Christian theologies that observe the very words of Jesus in the Gospels, when he sets the criteria with which his followers would be judged: if they helped the hungry, the thirsty, the foreigners, those who had no clothes, the sick and those in jail.[16] If Christian majorities and minorities would stand for an inclusive understanding of Human Rights, this would certainly help making these once more the language of the oppressed,[17] where the right to be free from torture and the desire to own property are no longer confused.

[1] Peter W. Edge and Graham Harvey, Law and Religion in Contemporary Society: Communities, Individualism and the State (Ashgate, 2000), 177.

[2] Elio Gaspari, “Carter, Si!,” The New York Times, April 30, 1978, sec. Archives, https://www.nytimes.com/1978/04/30/archives/carter-si.html.

[3] Costas Douzinas, The End of Human Rights: Critical Thought at the Turn of the Century (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2000).

[4] As I finish editing this piece, the International Court of Justice held its first part of the hearing on the case South Africa v. Israel, concerning alleged violations by Israel of its obligations under the 1948 Genocide Convention and international law in relation to Palestinians in the Gaza Strip

[5] Thomas Mertens, “Nazism, Legal Positivism and Radbruch’s Thesis on Statutory Injustice,” Law and Critique 14, no. 3 (October 1, 2003): 277–95, https://doi.org/10.1023/B:LACQ.0000005215.60293.99.

[6] Jacques Ellul, The Theological Foundation of Law (New York: The Seabury Press, 1969).

[7] Alexandra Xanthaki, “When Universalism Becomes a Bully: Revisiting the Interplay Between Cultural Rights and Women’s Rights,” Human Rights Quarterly 41, no. 3 (2019): 701–24.

[8] Genesis 1:26-27

[9] Juliana Neuenschwander Magalhães, “O paradoxo dos Direitos Humanos,” Revista da Faculdade de Direito UFPR 52, no. 1 (2010), http://ojs.c3sl.ufpr.br/ojs/index.php/direito/article/view/30694.

[10] See: W. J. T Mitchell, “Cloning Terror: The War of Images 2001–2004,” in The Life and Death of Images: Ethics and Aesthetics, ed. Diarmuid Costello and Dominic Willsdon (Cornell University Press, 2008). Also check: De Matos, Jesus Fights back: Easter torture and reverse racism (Critical Legal Thinking, 2022), https://criticallegalthinking.com/2022/06/30/jesus-fights-back-easter-torture-reverse-racism/

[11] Congresso em Foco, “Em meio à polêmica do Enem, Bolsonaro chama direitos humanos de ‘esterco da vagabundagem,’” Congresso em Foco, November 5, 2017, https://congressoemfoco.uol.com.br/projeto-bula/reportagem/direitos-humanos-e-“esterco-da-vagabundagem”-diz-bolsonaro/.

[12] “Evangelical Activist Shane Claiborne Wants to Beat Our Guns into Plowshares — Really,” Los Angeles Times, April 3, 2019, https://www.latimes.com/opinion/op-ed/la-ol-patt-morrison-shane-claiborne-guns-christians-20190403-htmlstory.html.

[13] Jason Horowitz, “Pope Francis Criticized Family Separations Before Policy’s Reversal,” The New York Times, June 20, 2018, sec. World, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/20/world/europe/pope-francis-trump-child-separation.html.

[14] “Situation in Ukraine: ICC Judges Issue Arrest Warrants against Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin and Maria Alekseyevna Lvova-Belova | International Criminal Court,” accessed January 9, 2024, https://www.icc-cpi.int/news/situation-ukraine-icc-judges-issue-arrest-warrants-against-vladimir-vladimirovich-putin-and.

[15] “Self-Determination Integral to Basic Human Rights, Fundamental Freedoms, Third Committee Told as It Concludes General Discussion | UN Press,” accessed January 10, 2024, https://press.un.org/en/2013/gashc4085.doc.htm.

[16] Matthew 25:35-45

[17] Costas Douzinas, “What Are Human Rights?,” The Guardian, March 18, 2009, sec. Opinion, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/libertycentral/2009/mar/18/human-rights-asylum.

Marcus De Matos is a Lecturer in Public Law at Brunel University London, where he co-leads the Research Group on Human Rights, Society and Arts. He is an Honorary Member at the Institute of Brazilian Lawyers (IAB), and a board member of ABUB (IFES-Brazil) and the Brazilian Association of Students and Academics in the UK (ABEP-UK). He has also been the editor of Blog Dignidade!, a collective of Christian scholars who write about the principle of human dignity and occasionally translated Red Letter Christians materials to Portuguese language.

Leave a Reply