Telescopes have been troublemakers for centuries. They’ve revealed that the Earth is not the center of the universe, not even the center of the solar system. They showed us our sun was just one of many stars in our galaxy, then showed us our galaxy is just one of many in the universe. They provided the evidence that the universe is expanding, which in turn implied the beginning of the universe in the Big Bang. Now the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is adding wrinkles to our understanding of how those galaxies formed in the wake of the Big Bang.

The power of telescopes is enabling us to observe beyond the limits of our unaided senses. For all that anyone can see or experience on their own, everything might as well revolve around the Earth. Only when we look farther–farther out into space, farther back into time–are we challenged to expand our understanding. Over and over, we find that our models are limited. They work fine for what we knew previously, but when pushed beyond the limits of the data which validated them, they sometimes need to be updated to accommodate the new data.

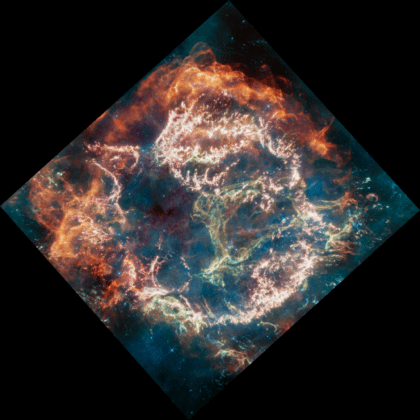

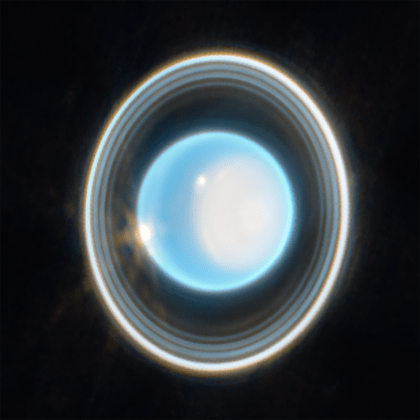

In the coming years, we can expect lots of new data from JWST. It is much farther away from the Earth than the Hubble Space Telescope, providing a different perspective on local space. And it has the capability to see infrared light much better than other telescopes. On Earth, telescopes can’t see much infrared light from space because it is absorbed by the atmosphere. Hubble doesn’t do as well with infrared because its own mirror is warm enough to emit infrared light itself. By virtue of its greater infrared capabilities, JWST can see farther than other telescopes. Farther into space because infrared light is not impacted by space dust as much as visible light is, so more of it can reach us from distant objects. Farther back into time because the expansion of the universe shifts light to be more red the more space that light travels through. The visible light from very old (and very far away) objects has been shifted so much towards the red that some of it is infrared by the time it reaches us.

It is still early days, but those infrared observations of the very old, very distant universe have already created a stir. We are able to see some of the earliest galaxies that ever formed in the universe. We can compare what we see to universe-forming simulations based on gravity and other physical principles. The results of those simulations depend on various parameter values, which have ranges of plausible values. We could use a limited data set from Hubble about early galaxies to choose parameter values. However, some early results from JWST deviated from the predictions calibrated by what we had seen before. We expected small, simple galaxies, but what we are seeing are bigger (or at least brighter) and more numerous. Do we need a new model, or simply better parameter values?

These un(der)expected findings have been a boon for science journalists and sites looking to generate science-related clicks. When scientists are surprised or puzzled, when paradigms are potentially being overturned, the opportunities for exciting headlines are extensive. For folks like me, and I imagine many of you, who are not astronomers or cosmologists, it can be difficult to assess what is hype and what is real. The excitement of the frontline physicists is understandable; JWST is a once-in-a-generation device that has the potential to make careers. Given the investment of time and resources behind it and the technological innovation it represents, simply confirming what we already know would be a bit of a disappointment. With those incentives and the tendency for buzz to build around the results which stand out rather than those which are in line with existing models, the potential for hype is there. But that doesn’t mean there aren’t real surprises and real discoveries also.

It struck me that theology doesn’t exactly seem to have these same kinds of issues. Maybe I’m wrong, but it I don’t see where theology regularly gets new data. Sure, new questions arise as we invent new circumstances; theologians in antiquity didn’t have to answer detailed questions about the ethics of AI. But for Christian theologians, the basis for answering those questions remains the same: the Bible. Furthermore, I think that can be considered a feature, not a bug. Theology and religion orient daily life and address eschatological concerns; being wrong about cosmological models doesn’t have the same stakes. However, I am wondering if this is a reason why science and theology (or religion or faith or however you want to put it) don’t always seem to go together. Revising models and overturning paradigms is an expected and celebrated part of science. Whereas with Christianity, the stability the Bible or the Nicene Creed over millennia is part of the appeal. Obviously there is far more to both science and theology. But zoomed out, I can see where the impression of a fundamental tension in approach could be sensed.

Of course, with a long enough view of time, even theology gets new data. Having celebrated Easter just a few days ago, the obvious example of Jesus’ resurrection is impossible to ignore. The revolutionary nature of that event and the movement that followed dwarfs anything that might come from JWST or any other piece of scientific equipment. So maybe a way to approach that sense of tension is to recognize that in both science and theology, there is a time and a place for a change in perspective, and a time and a place for holding on to what we already know. Does that help me figure out what to believe from the JWST press releases? No, not really. But it does provide another opportunity to talk about how a familiarity with science can harmonize with a religious perspective and not undermine it.

Andy has worn many hats in his life. He knows this is a dreadfully clichéd notion, but since it is also literally true he uses it anyway. Among his current metaphorical hats: husband of one wife, father of two teenagers, reader of science fiction and science fact, enthusiast of contemporary symphonic music, and chief science officer. Previous metaphorical hats include: comp bio postdoc, molecular biology grad student, InterVarsity chapter president (that one came with a literal hat), music store clerk, house painter, and mosquito trapper. Among his more unique literal hats: British bobby, captain’s hats (of varying levels of authenticity) of several specific vessels, a deerstalker from 221B Baker St, and a railroad engineer’s cap. His monthly Science in Review is drawn from his weekly Science Corner posts — Wednesdays, 8am (Eastern) on the Emerging Scholars Network Blog. His book Faith across the Multiverse is available from Hendrickson.

That’s really awesome! Your dad must be so proud of you. I used to work with him at PH and I also lived nearby in Clifton. Congratulations!