For everything there is a season, and now that we have passed the Autumnal Equinox, when the sun is directly over the Equator and days and nights are nearly equal length, we have officially transitioned from summer to autumn in the northern hemisphere. For many people, Fall means it’s time to get out sweaters, decorate with gourds, and partake of traditional autumnal foods and beverages (pumpkin spice latte, anyone?). For some people, autumn means it’s time to bring in the rest of the crops and garden vegetables. Others start getting ready for hunting season. For some folks near the Great Salt Lake in Utah it is time to get ready for Brine Shrimp Season!

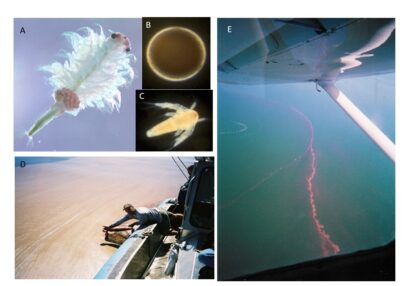

Anyone who has tried to raise Sea Monkeys is familiar with brine shrimp. They are tiny shrimp that live all over the world in very salty lakes like the Great Salt Lake in Utah and Mono Lake in northern California. Scientists think they are originally from the Mediterranean, and they diverged from an ancestral form ~ 5.5 million years ago. For most of the year, females are ovoviviparous, which means they produce eggs that remain inside their bodies until they are fully developed and ready to be released as free-swimming larvae. In late summer, shorter days and extremely salty water cue females to become oviparous, and they release embryos, that are enclosed in a hard shell, into the water column. The embryos, or cysts, enter diapause and remain in this dormant state through the winter. What is remarkable about this species is that they are able to turn themselves off so completely that their oxygen consumption is barely detectable. They are also highly resistant to desiccation and extreme cold, and they can survive in an environment that lacks oxygen.

God spoke: “Let us make human beings in our image, make them reflecting our nature

So they can be responsible for the fish in the sea, the birds in the air, the cattle,

And, yes, Earth itself, and every animal that moves on the face of Earth.”

God created human beings; he created them godlike,

Reflecting God’s nature. He created them male and female.

God blessed them: “Prosper! Reproduce! Fill Earth! Take charge!

Be responsible for fish in the sea and birds in the air, for every living thing that moves on the face of Earth

(Genesis 1:26-28, The Message)

The ability of brine shrimp to resist such extreme environmental conditions makes them a valuable commodity. Over 2,000 metric tons of dry cysts are sold each year to be used as food for fish and crustaceans in the aquaculture industry as well as for smaller scale aquariums. They are also used in bioassays to test the toxicity of chemicals. And then there is the Sea Monkey industry.

When I started using brine shrimp for my Ph.D. dissertation research in 2000, I had no idea that they were part of such a huge industry. I was even more surprised to learn that harvesting brine shrimp from the Great Salt Lake is an enterprise defined by competition, intrigue, and even sabotage. In fact, the competition is so fierce that the person who worked with me to collect brine shrimp from the lake wouldn’t disclose the name of the company he worked for. Some of the stories he told are not suitable to publish here.

One reason that the brine shrimp harvest is so competitive is that the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources carefully manages the Great Salt Lake brine shrimp populations. Before the season starts each year, they take samples to learn how many shrimp are present and how many can be harvested without harming the lake ecosystem. They issue a limited number of permits (one per harvesting boat) based on those numbers. Then, when the season opens on October 1, it becomes a free-for-all that, according to the stories, sort of resembles a church Sunday School Easter Egg Hunt. Once the predetermined number of cysts is collected, brine shrimp season ends for the year.

So why am I writing about the brine shrimp harvest? One reason is that the brine shrimp industry is something that relatively few people are aware of, but we shouldn’t take it for granted. Anyone who eats farmed fish or shrimp benefits from this industry. The main reason is that I think that the way the harvest is managed in Utah, at least from an ecological perspective, is a great example of how we, as Christians, should manage Creation in general. Stories of sabotage aside, the example of monitoring the lake and limiting the amount of shrimp taken to preserve the ecosystem is something we should require any industry that harvests natural resources to follow.

Dr. Julie A. Reynolds is a Research Scientist at The Ohio State University in the department of Evolution, Ecology, and Organismal Biology. She studies insect physiology and biochemistry with the goal of learning how animals adapt to extreme environments and survive changes in climate. In addition to writing for the Emerging Scholars Network, she is actively engages in discussions about science and faith as a Sinai and Synapses Fellow.

Leave a Reply