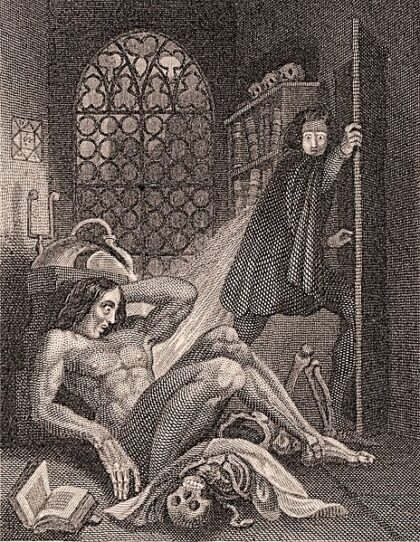

“Life, although it may only be an accumulation of anguish, is dear to me, and I will defend it” is a quote from Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, the novel which spurred my love of research and people in a new direction as I explored my academic voice through my undergraduate thesis. This passion for exploring human instincts and connection quickly led me to a master’s degree, also in literature. In my current role as higher education staff, I sit uniquely between graduate students and faculty in a position that provides coordination, mediation, and an unquestionably faithful presence to two often desperate and frantic populations in the academy.

My undergraduate thesis was titled, “A Reflection of Humanity in the Works of Mary Shelley”. I argued that, in Frankenstein, Shelley articulates the deepest need of humanity: companionship. Because both the creature and Victor are alienated from every other relationship in their lives, they become inextricably linked to each other in a toxic relationship of cat and mouse, threats and empty promises.

This isn’t that different from Graduate school, right? Student and advisor get so intrenched in research that they lose sight of much else. The advisor—concerned with the funding they need to keep their job; the student—concerned with graduation and the weight of the job search. These pressures mount as the naturally occurring obstacles of research are compounded by unnatural occurrences like bureaucracy and the IRB! Both parties could benefit from someone who can help them take the blinders off, shake out the mind worms, and breathe deeply.

They need someone to gently remind them 1) the only expectations you have to meet are those that will allow you to thrive, 2) you are human, and 3) there are advocates for 1&2. Of course, faculty tend to have more people to provide this support in the way of collaborators, mentors from their own time in graduate school, resources and programming across campus or other professional organizations. Students, if they’re lucky, can find one or two people to send them a life-jacket when they’re drowning if they even know where to look.

I have the privilege and honor of being this person to around 100 PhD students. I am the first point of contact for students during the application review process, and am often the final contact as I elicit responses to our exit survey from graduates. Throughout the in-between, I identify myself to students as the “first line of defense,” ready to direct them to answers and resources for whatever question or challenge they’re facing. My role providing academic and student services for graduate students can be summarized as advocacy or defending their opportunity to thrive as humans. I make sure students have and understand all of the resources they need to be successful in their program and beyond. This means that I often get to be the first person to ask students, “do you feel successful right now?” and “do you know what you need to feel so?” and sometimes offering recommendations when the answer is, “I have no idea.” This also means translating those needs to administration and faculty in a manner that allows them to quickly and thoroughly provide support for solutions, without heaping more onto their already overflowing plates. Essentially, I’m a traffic director: raising signals and slowing traffic enough for people to safely move from point A to point B.

Personally, I went to graduate school because I love reading and thinking deeply about what I’m reading. Unfortunately, I didn’t realize what a sacrifice it is to do what you love, and I quickly fell into burnout and depression within the two years of my master’s program. I watched the doctoral students in my department (with a very dead job-pool waiting for them) and thought “how on earth do they have the mental and emotional capacity to keep doing it?!” I lived in a Frat House as a House Director so that my husband and I could reasonably live off our master’s degree stipends. I made $8K a year. I left a teaching job in search of more work-life balance and work I was passionate about’.so I got one out of two.

Even though I was doing what I loved. I felt lonely and empty inside. I felt always stressed and never qualified or capable of meeting expectations. I almost dropped out my first semester until my final paper had the feedback “you have a weak argument’but you’re where you should be.” What the professor meant was “this is not great, but you’re a student so you’re headed in the right direction.” I had never understood that before in my life. It was a lightbulb moment for me. Suddenly failure wasn’t possible because, well, that just means I haven’t learned that thing yet and that’s all normal and good. But so many of my peers did not receive that message. My vocation is to change that by reinforcing this message early and often to the graduate students I serve.

I do so many different things in my job as a Graduate Education Professional (sounds fancy). But the most important thing that I do? That’s to remind the graduate students that:

- They don’t have to meet my expectations; I only want to help them do what leads them to thrive.

- They are human and have reasonable needs as such.

- My job is to advocate for points 1 & 2.

Have you ever heard the sigh of relief from a student when you offer to give them pointers on how to have a difficult conversation or write a scary email to their boss?

Have you ever sat with a student moved to tears (of sadness or anger) because they can’t imagine ever being good enough in their research to please their faculty?

Have you ever heard the gratitude in a student’s voice over the phone as you tell them, without judgment, how to leave the program for something that’s a better fit for them?

Whether you’ve been able to sit with graduate students in these experiences or not, you likely understand feeling stuck, overlooked, confused, and longing to reach a goal you’ve been dreaming of and striving towards. Hopefully, you also understand the difference it made to have someone tell you that you’re on the right track and ‘right where you should be’. When you have a cheerleader faithfully standing behind or beside you along the way, you’re bolstered to dig deep and continue the race. And how many of us, when we’ve completed something we thought would break us, have carried that knowledge of our strength into future endeavors.

Empathy, intentionality, and vulnerability are necessary contributions to a graduate student’s professional development. The encouragement and morale I provide to graduate students during their program are tools and messages I trust they carry throughout the rest of their professional, and perhaps personal, journeys. Mary Shelley’s creature moves me deeply when he says, “I do know that for the sympathy of one living being, I would make peace with all. I have love in me the likes of which you can scarcely imagine’” Therefore, I choose to remain a faithful presence to my students by providing them the sympathy of one.

Allie Burns is the Academic Coordinator for the University of Tennessee-Oak Ridge Innovation Institute and has been involved in InterVarsity both as an undergraduate, graduate student, and volunteer. She utilizes her degrees in English Literature to provide resources in communication and mediation to the students and faculty she serves. When she’s not answering her emails or planning events, she enjoys drinking local coffee, completing jigsaw puzzles, and collecting Frankenstein memorabilia.

Leave a Reply