This is Part 3 in a five-part essay series. A version of this essay was originally published online and in print as part of “Faithful Presence in the Midst of Pluralism: Three Tensions” at Ad Fontes.

In the previous essay, we considered the tension between affirmation and antithesis. Faithful presence further involves living in the tension between engaging the world and remaining distinct from it. In fact, these two tensions depend upon one another: it may be easier to avoid the distortions of engagement and distinctness by keeping in mind the goal of balancing affirmation and antithesis (rather than sliding into either synthesis or negation); at the same time, successfully holding affirmation and antithesis together requires Christians both to engage, and to do so from the fullness of our distinctness as Christians.

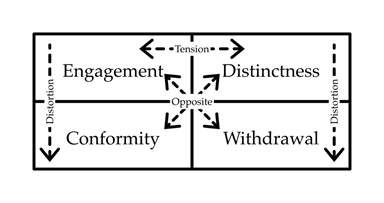

Just as we differentiated affirmation and antithesis from synthesis or negation, engagement and distinctness must be distinguished from their distortions. The distortion of engagement, which often masquerades as it but is in fact a perverted form of it, is conformity. This can mean the conformity of Christians to the world, as happens when Christians try to be relevant to the world, but find ourselves gradually becoming more like the world. Or it can mean insisting that the world conform to (a particular interpretation of) Christian principles, so that there is no longer a distinct world to engage. On the other hand, the distortion of distinctness is withdrawal, such as that manifested by various forms of Christian separatism. In the same way as affirmation becomes synthesis when it ceases to be united with antithesis, and antithesis becomes negation when it ceases to be united with affirmation, so too engagement becomes conformity when the engagement no longer comes from a place of distinctness, and distinctness becomes withdrawal when it is no longer oriented toward engagement.

The tension between engagement and distinctness[1]

Christian ethicist Luke Bretherton points out that any given instance of similarity between the church and the world may be a failure to maintain the church’s distinctiveness, but need not necessarily be so: “the church can often be like the world in good and generative ways. It can also be unlike the world in negative and degenerative ways.”[2] Bretherton calls for a “case by case evaluation” rather than a total dismissal of anything that looks too similar to the world, recognizing that “at the level of social practice, we should expect to see both convergence and divergence of practice; that is, the social practices of Christians will not, of themselves, always be distinctive from the practices of non-Christians.”[3]

This combination of “both convergence and divergence” results in a tension: “The church is both fashioned out of the world, and hence is like the world, and yet it is fashioned in response to the Word of God, and therefore, is unlike the world.”[4] In consequence, Bretherton encourages us to pursue specificity (i.e., living in specifically Christian ways) rather than distinctness merely for the sake of being different from our non-Christian neighbors.[5] And he reminds us that Christians are pilgrims, in but not of the world, and so will experience “both distance and belonging,” rather than either withdrawal or assimilation.[6]

Like Bretherton, James K. A. Smith recognizes both the difficulty of dwelling in this tension and the importance of doing so well. Referring to the challenges of engaging in Christian formation in the midst of powerful influences from the surrounding culture, he postulates, “it may be the case ’ that a Christian community that seeks to be a cultural force precisely by being a living example of a new humanity will have to consider abstaining from participation in some cultural practices that others consider normal.”[7] Such abstention might sound like separatism. But the essential difference, Smith explains, is not in the actions of abstention and separation themselves, but rather in the purpose to which they point:

[T]he abstention would not be primarily negative or protective: it would be undertaken in order to engage in cultural labor otherwise, to unfold cultural institutions that are ordered by love and aimed at the kingdom, cultural practices that are foretastes of the new creation and that, as such, would themselves function as winsome witness to God’s redemptive love.[8]

Thus, Smith does see a role for cultural engagement, and an important one at that. Even so, he insists that such engagement must be distinctively Christian, and this can only happen by means of selectively abstaining from certain practices and norms of the surrounding culture. Yet such abstention does not serve the end of resistance merely for the sake of being different, but rather creates space for forming alternative, more genuinely Christian practices and habits.

[1] Figure courtesy of Luke Herche. Used by permission.

[2] Luke Bretherton, Hospitality as Holiness: Christian Witness Amid Moral Diversity (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2006), 106.

[3] Bretherton, Hospitality as Holiness, 107; similarly, Christian teacher educator David I. Smith points out that the story within which Christian educators live matters more than the distinctiveness of the practices in which they engage. See Smith, On Christian Teaching: Practicing Faith in the Classroom (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2018), 129-130.

[4] Bretherton, Hospitality as Holiness, 108.

[5] Bretherton, Hospitality as Holiness, 109-110.

[6] Bretherton, Hospitality as Holiness, 111-112.

[7] James K. A. Smith, Desiring the Kingdom: Worship, Worldview, and Cultural Formation (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 2009), 209, emphasis original.

[8] Smith, Desiring the Kingdom, 210, emphasis added.

Emily G. Wenneborg is Director of Pascal Study Center and Assistant Professor at Urbana Theological Seminary. She has a PhD. in Philosophy of Education and Religious Studies from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Emily is interested in the possibilities and tensions of formation for Christian faithfulness in the midst of deep pluralism.

Leave a Reply