“There we shall rest and see, see and love, love and praise. That is what shall be in the end without end. For what other end do we propose to ourselves than to attain to the kingdom of which there is no end?”

—Augustine, The City of God

Lifelong, Sir Ebenezer Howard (1850-1928) was employed as a clerk helping to produce the official record of the Parliament. But he is best known for his avocation: an abiding desire to address the dehumanizing impact of urbanization in late nineteenth-century England. In Howard’s day, record numbers of young adults were abandoning rural life to pursue better economic and social prospects in the city. In fact, conditions in cities like London could be wretched—polluted air, raw sewage in the streets, disease, inadequate housing, and limited opportunities for sustainable employment. Moreover, this exodus from the countryside greatly diminished the economic vitality and social fabric of rural communities.

In 1899 Howard established the Garden City Association. He envisioned a new kind of community in which a garden would be the organizing principle for all labor, commerce, learning, and leisure, and in 1902 he published his treatise Garden Cities of To-morrow. According to Howard:

The country is the symbol of God’s love and care for man. All that we are and all that we have comes from it. Our bodies are formed of it; to it they return. We are fed by it, clothed by it, and by it we are warmed and sheltered. On its bosom we rest. Its beauty is the inspiration of art, of music, of poetry. . . Town and country must be married, and out of this joyous union will spring a new hope, a new life, a new civilization.[1]

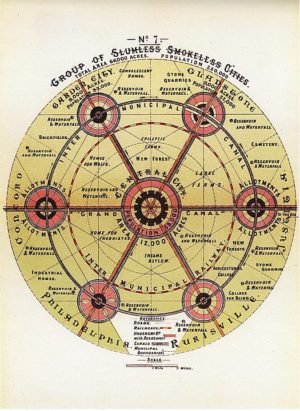

Howard’s plan allowed for generous green spaces and carefully sited zones for industry, commerce, and art. His egalitarian city would be “slumless” and “smokeless” and make provision for neglected groups like “waifs” and the “insane.” Wrote Howard: “Human society and the beauty of nature are meant to be enjoyed together.”[2] Geometric symmetry formed the basis of the innovative design that would showcase this concord. And desiring to meld Town and Country, boulevards would radiate like spokes from the central city, connecting village dwellers to farms and forests beyond. Bisecting these arteries were concentric circles of municipal canals and railways to ease the movement of goods and people. Finally, a five and a half acre, well-watered garden would establish the city’s vital center.

Howard’s aesthetic scheme was shaped, in part, by John Ruskin (1819-1900), a celebrated British art and architecture critic, philosopher, and painter, and it was utopian in every respect. For such a community to become a reality, critical assumptions regarding ownership, the viability of his financial model, and general human agreeableness would be essential. Even so, at least two Garden City communities—Letchworth Garden City and Welwyn Garden City—were built in Hertfordshire County, England and numerous cities in the United States adopted aspects of the plan, as well.[3]

More than a century has passed since Howard first observed the problematic nature of the modern metropolis. It is caught up in a treacherous irony: to support expansive urban sprawl, proximate rural land must be developed. That is, the agrarian places and people that exist to supply grocers and restaurants with food are displaced and global enterprises systematically rush in to meet the newly created need. The contours of this problem are beyond the scope of this modest post, but the contradiction it raises should not be missed: increasingly, only the privileged can afford to retreat to the land—its lakes, rivers, forests, and meadows—even as their economic welfare relies, in part, on its continued consumption.

In the face of unending urban expansion, how extraordinary to observe that, since 1950, Detroit, Michigan has lost an estimated 60% of its population. Many factors contributed to the emptying of America’s Motor City, including a devastating race riot in 1967, corresponding white flight, the destabilization of the auto industry in the late ‘90s, and gross fiscal mismanagement, even Chapter 9 bankruptcy in 2013. Responding to the city’s unprecedented degradation and decay, derelict homes and public and commercial buildings were razed, leaving behind thousands of empty lots.

Then something counterintuitive occurred. Enterprising residents saw an opportunity. They cleared litter and weeds from these parcels, cultivated the soil, and planted gardens. A nascent movement of urban farms took hold, and by 2018 Detroit boasted an estimated 1,500 gardens with some 23,000 community members participating.[4] Season by season, the older city grid was organically infilled. If one flies in or out of the Detroit Metro Airport on a spring or summer day, she will behold the crazy quilt pattern of green, tan, and gray that is urban Detroit. In season, fresh vegetables and fruit now prosper in what had been a food desert, and horticulture is a new occasion for place making. Detroit may still be on life support, but fruitful gardens are making an important contribution to the restoration of the city’s economic and cultural renewal.

Unlike Detroit’s grassroots garden initiatives, Ebenezer Howard’s vision was largely top-down. Still, one can imagine him celebrating planted city gardens as a tangible means to restore human dignity. New empirical studies in Philadelphia further demonstrate that when green spaces are established and tended, violent crime is measurably reduced.[5] The new initiatives in Detroit and Philadelphia may not bear the aesthetic character of Howard’s well-ordered design, but they surely do capture its ethos.

The gardens scattered about the city of Detroit are not designed by landscape architects, nor are they carefully maintained by botanists and groundskeepers. No matter. From formal rose gardens to backyard vegetable plots, and from commercial hydroponic enterprises to the restoration of prairies, wetlands, and forests, every green space is a place for the biosphere to breathe. As Frederick Law Olmstead, the primary designer for Central Park, envisioned in 1858, his 843 acre installation would one day become “the lungs of New York City.”

This four-part blog series examines the significance of God’s garden in Eden. We began by considering the opening chapters of Genesis, but now we turn to the Apostle John’s vision of God’s new city. Its architectonic structure measures 1,500 miles in width, depth, and height (Rev 21:16)—a perfect cube and one that echoes the perfect cube the Holy of Holies in Solomon’s Temple: “The interior of the inner sanctuary was twenty cubits long, twenty cubits wide, and twenty cubits high; he overlaid it with pure gold” (1 Kings 6:20). In the mind of these biblical writers, idealized geometric form was a tangible means to communicate the perfection of God’s being and presence—a sensibility embodied in Howard, who may also have been inspired by the Apostle John’s vivid description of God’s city:

Then the angel showed me the river of the water of life, bright as crystal, flowing from the throne of God and of the Lamb through the middle of the street of the city. On either side of the river is the tree of life with its twelve kinds of fruit, producing its fruit each month; and the leaves of the tree are for the healing of the nations. Nothing accursed will be found there any more (Rev 22:1-3, NRSV).

St. Augustine commenced writing his magisterial City of God in 413, likely prompted by the Sack of Rome in 410 by the Visigoths. But as Thomas Merton points out, “It is a theology of history built on revelation, developed above all from the inspired pages of St. Paul’s Epistles and St. John’s Apocalypse.”[6] Augustine’s tome is philosophical and theological in nature, a divine picture of restored humanity, wherein the disgrace and discord of Adam and Eve’s disobedience finds resolution. Babylon, the empire besotted by the grandeur of human achievement, has been defeated and salvation for God’s elect is won. According to Augustine, “The peace of the celestial city is the perfectly ordered and harmonious enjoyment of God, and of one another in God. The peace of all things is the tranquility of order.”[7]

The center of God’s city is not Babel’s tower but God himself. The light of that city is his very being. The water of life flows from his throne to sustain a garden. In the end then, is the beginning, for at the center of God’s great city is his beloved garden, one he has preserved for all time to be a resplendent place of shalom. There the nations and its many peoples will finally be healed. At last, we will be at home.

_______________

[1] Ebenezer Howard, Garden Cities of To-Morrow, Illustrated Edition (Gloucester, UK: Dodo Press, 2009), viii.

[2] Ebenezer Howard, Garden Cities of To-Morrow, vii.

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Garden_city_movement

[4] https://urbanland.uli.org/industry-sectors/public-spaces/growing-city-detroits-rich-tradition-urban-gardens-plays-important-role-citys-resurgence/

[5] Eugenia C. South, “Opinion | To Combat Gun Violence, Clean Up the Neighborhood,” The New York Times, October 8, 2021, sec. Opinion, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/08/opinion/gun-violence-biden-philadelphia.html.

[6] Saint Augustine, The City of God, trans. Marcus Dods, intro. Thomas Merton (New York: Random House, 1950), ix.

[7] Saint Augustine, The City of God, 690.

_______________

This is the fourth in the series on An Artist Looks at Genesis. The earlier posts are:

Cameron Anderson is an artist and writer and lives in Madison, Wisconsin. Cam currently serves as Associate Director of Upper House. With G. Walter Hansen, he is the co-editor of God in the Modern Wing: Viewing Art with Eyes of Faith (IVP Academic, 2021) and the author of The Faithful Artist: A Vision for Evangelicalism and the Arts (IVP Academic, 2016).

Leave a Reply