In this article, historian David Thomas argues that the historian’s work, with evidence and narratives of the past, is a disciplined form of remembering. Drawing on the work of historian Gerda Lerner, he writes, “A look backward enlarges and helps make sense of our present while suggesting hope and direction for the future.

_______________________________________________________________________________

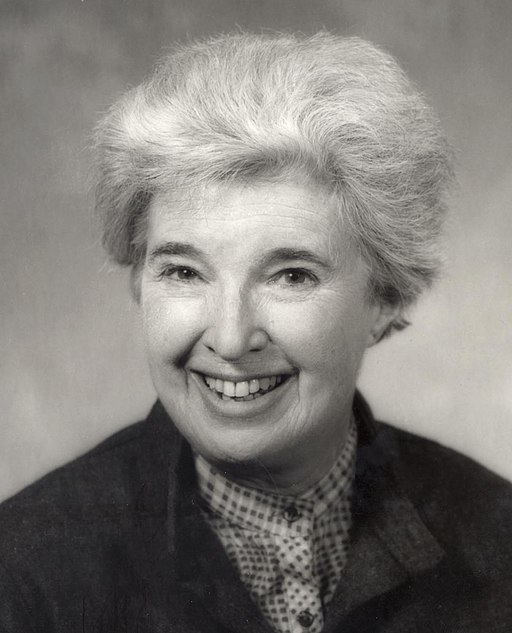

The network of evidence, argument, narrative, and purpose that pulls together to form a history is complex beyond knowing. And yet, despite the complexity and the incompleteness, historical narrative remains essential to human understanding. Narrative communicates human experience more personally and more meaningfully than abstractions; it is, as Alasdair McIntyre argues, the fundamental way in which people make sense of their experiences. Historian Gerda Lerner exemplifies this in her poignant and powerful essay, “Living in Translation.” The essay reflects back on her experience fifty years prior as an Austrian and Jewish refugee fleeing the Nazis in the 1930s. Let me quote the first paragraph at length, for it illustrates how tightly interwoven narrative and purpose can be, as well as the historian’s call to destroy falsity and recover truth:

When I came to the United States in 1939 as a refugee from Hitler fascism, I had, like all refugees, a very problematic relationship with the English language. On the one hand, I wanted desperately to learn English and to speak it well. This was my meal ticket, absolutely essential if I was to get work. On the other hand I felt a responsibility to uphold, treasure and keep intact the integrity of the German language which fascism had stolen from me, as it had stolen all my worldly possessions. The Nazis spoke a language of their own – first a jargon of slogans and buzz words; later the language of force and tyranny. Words no longer meant what they said; they meant what the Nazis intended them to mean, and so, gradually, they became empty of meaning. Like banners flapping forever in the wind, they flapped around the skeleton of German speech until all that could be heard was the clattering words pretending to meaning they could not encompass. Seen in that light, it was the obligation of every antifascist German-speaking refugee to uphold the old language, so that some day it might be restored.[i]

Lerner, one of the great historians of the twentieth century, offers no illusions about objective detachment. Memory, narrative, and purpose are inextricably linked. Devotion to what was, especially to the German language that was stripped, falsified, and emptied of meaning by the fascists, became a central motive to remember and restore the older, meaningful German. However, Lerner’s devotion, expressed as a commitment to language, also contains the dedication to people who need and want the meanings that the “old language” communicated. That obligation to remember was to Lerner a “heavy burden,” emphatic and essential, a feature of life that could not be put aside. “One cannot forget and one must not forget and one must be a witness.” This conviction shaped much of Lerner’s career, most especially her commitment to remember and tell the stories of those whose stories were (and are) left largely untold: women, the poor, slaves, colonials, and others.[ii] The threads of personal narrative, historical reality, and purpose are tightly woven.

Once this interweaving is seen, it’s hard to unsee. The link between the historical past, personal narrative, and contemporary purpose is foundational to the InterVarsity Race Course, an ongoing (as of this writing) exploration of what “Blackness” means and how it matters. It’s integral to Bryan Loritts’ autobiographical assessment of white evangelicalism, Insider, Outsider. It undergirds Thomas Childers’ histories of World War II, and Karl Marlantes lament over Vietnam. The political and racial conflicts of the past year gain clarity with greater understanding of our deep past and the personal narratives of those involved. C. S. Lewis wrote many years ago that people engage with the past because they need something to set against the present and the future is not available.

I want to put a slightly finer point on that. Engaging with the past links historical reality, contemporary personal and communal narratives, and our purposes for the future. A look backward enlarges and helps makes sense of our present, while suggesting hope and direction for the future. By contrast, when the past becomes merely past we might hang it on the wall in the nearest Cracker Barrel as an antiquarian relic slowly rusting away. Disconnected from the present by forgetfulness, it has nothing much to say to us, either to forgive or condemn, empathize or inspire, release or guide. With no connection, we can swap out our historical decorations as our fashion sense dictates. The heavy burden to remember that Lerner wrote about, or the clarion call to remember that bursts through the Scripture, this remembering provides meaning for the present and hope and direction for the future. Give math and science their due for their problem-solving abilities. But remembering whose we are and how we got here – the remembering, not the mythmaking — that’s the burden and the gift which links memory and hope.

____________________

[i] Gerda Lerner, “Living in Translation,” in Why History Matters: Life and Thought (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), 33.

[ii] Lerner, “Of History and Memory, in Why History Matters, 52-53.

David Thomas is Professor of History at Union University in Jackson, Tennessee. His Ph.D. in History is from The Ohio State University. Prior to that he earned a Master’s in Oceanic Science from the University of Michigan and was gainfully employed as an Oceanographer in California. He has published one book on historical representation in children’s literature (The Stories We Tell Our Children, Royal Fireworks Press, 2008) and is working on a theology of history. Married, father of three, grandfather of three, and a member of All Saints Anglican Church in Jackson.

Leave a Reply