Welcome back to our Sci-Fi Film Festival. This week, I continue my conversation with Mike Beidler about Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace (TPM) as we chat about canons and legends. You can find the first half of the conversation here, including details about Mike’s own role in the storytelling of Star Wars and his in-universe counterpart Myk Bidlor.

Andy Walsh: What elements, if any, would you prefer were not part of the Star Wars canon?

Mike Beidler: In terms of elements from TPM that I would prefer never to have been part of Star Wars canon, I can sum it up in two words: comic-relief amphibian. You can eject Jar-Jar Binks out of the nearest airlock for all I care. And while we’re performing summary executions, let’s throw into the airlock all that boring political talk about disputed taxation of trade routes and (sorry, Andy) midichlorians. Regarding the former, I thought George made the political scene too complex for the average viewer; regarding the latter, I thought boiling down Force potential into something that could be scientifically ascertained robbed us of the quasi-religious qualities that gave the Force an air of sublime mystery. I should have known it was coming when my author friend Kevin J. Anderson was, back in 1993, instructed by Lucasfilm to create a scientific means to detect one’s Force potential for his Jedi Academy trilogy (1994).

AW: I know I’m way out on a limb when it comes to midichlorians. I find endosymbiosis more sublime than mystery, but that may very well just be me. Speaking of wanting to eliminate elements of the film, I’m guessing you are familiar with The Phantom Edit and other fan attempts to create a version of TPM more to their liking (like Topher Grace editing all three prequels into a single film). Have you watched any of them? Do you have any opinions about such fan participation culture?

MB: I’m familiar with The Phantom Edit, but it’s been a long time since I’ve seen it. I do remember it being a pretty brilliant distillation of the original film, and Lucasfilm’s unwillingness to pursue legal action against editor Mike J. Nichols is telling. I appreciated Nichol’s excising of certain childish excesses that make me cringe when watching TPM today and giving George’s story a little more gravitas to match the tone of the original trilogy (minus Ewoks). I also loved its midichlorian-less nature. I have not, however, seen any of the other fan edits. In the end, I think serious fan edits of films are valuable to filmmakers and storytellers in that they allow for a more detached look at the pacing and storytelling techniques of whatever body of work is under examination. One of my favorite non-Star Wars fan edits is the Alternative Edition Redux of David Lynch’s Dune (1984).

AW: Is Disney’s excising of the entire slate of non-film stories (including Myk Bidlor) the most sweeping version of these remixes, or is it something else?

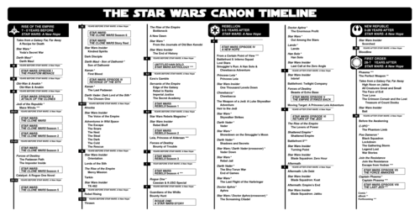

MB: When the newly commissioned Lucasfilm Story Group decided in 2014 to re-brand everything in the Star Wars Expanded Universe (EU) – including nearly 40 years’ worth of previously canonized stories – as “Legends”… well… I felt a great disturbance in the Force, as if millions of stories suddenly cried out in terror and were suddenly silenced. I feared something terrible had happened.

AW: Do you think the idea of a canon is useful for talking about fictional storytelling?

MB: I’m actually of two minds on this. The Western aspect of my mindset appreciates the attempt to make a “universe” of stories consistent within itself, making the storytelling space feel more real and, at times, personally relevant. However, the concept of canon can also impede the art of storytelling, especially if the “universe” is physically small or relies on a too-small set of core characters to carry the “universe” along even though the space in which to tell the stories is massive. Only so much can happen to a small number of characters. So if you dispense with the idea of a closed canon, there’s more room for good – and bad – storytelling.

Several years ago, in an anthology that analyzed the Star Wars EU titled A More Civilized Age: Exploring the Star Wars Expanded Universe (Sequart Organization, 2017), I contributed an essay on the concept of canon in the Star Wars universe. In the essay, I wrote:

Kenobi’s hints at a way out of the entire canon and continuity minefield, one that is logical, satisfying, and that – once the Kool-Aid has been consumed – adds a dimension to the many Star Wars stories, including those now labeled “Legends” and makes them evven more enjoyable. Quite simply, every Star Wars story is true’ from a certain point of view.

What gives us the right to accept the “certain point of view” argument? Well, we get a big hint right at the beginning of each Star Wars movie: “A long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away….” As with the “once upon a time” opening of children’s fables, we immediately know that old tales are being told, that we are hearing legends of people long dead and events long past. Similarly, the first crop of late-1970s Star Wars novels came with the subtitle From the Adventures of Luke Skywalker. Again, the reader should have perceived immediately that he or she was in the company of old tales, and that Luke had many adventures indeed. The trick to neatly resolving the canon and continuity debate is to adapt the films’ famous opening line for Luke Skywalker’s own galaxy. …

With centuries separating storytellers from their famous subjects, contradictions are inevitable. Even American legends barely a century old – tales of the Wild West, for instance – are wildly contradictory. Why should the legends of the Star Wars universe be any different? …

… if all Star Wars stories are approached as legends – including that which the Lucasfilm Story Group has declared canon – the argument about which stories are canonical and which are “Legends” simply vanishes! … From our new certain point of view, we don’t have to bend logic to make all of the stories fit together. We also don’t have to pass judgment on a given Star Wars story as having never happened. Instead, we can attempt to make the most logical tales fit and decide to call the rest apocryphal, or whatever term we like. From our new certain point of view, Star Wars apocrypha is to be enjoyed instead of swept under the rug.

What are your thoughts on canon in terms of the Star Wars franchise or any other?

AW: You mentioned the possibility of a canon impeding storytelling, which highlights a concern I have had about the Disney-era movies. They’ve mostly managed to make the Star Wars universe feel smaller to me. The previous films would mention and hint at people, places and events we had to imagine. Or they’d introduce entire concepts like podraces and create a sense of history, of a separate world that our story briefly intersects. Whereas the new films seem more content to revisit the familiar. I realize that’s a qualitative and subjective assessment, but to put it in musical terms, the Disney-era films feel like they are mainly producing new variations on existing themes whereas the first six films aimed to produce new themes. Some of those variations are entertaining and well-executed, but they are still variations.

These days, I think I find the concept of canon most appealing as a way of giving myself permission to ignore stories that I simply don’t have time for. I definitely have completist tendencies, an all-or-nothing approach to fictional worlds. It can get unhealthy if I am not careful, or at the very least tedious. So if I can look at something like, say, the Marvel TV show Cloak and Dagger and tell myself “That’s not really canon because those characters and plots will never show up in the movies” then it is easy for me to not watch the show and not feel as though I am missing out.

But of course canon can have the opposite effect. The smaller Disney-era Star Wars universe has still proven impossible for me to keep up with. I read some of the comics on Marvel Unlimited, and I watched Rebels with my kids, but I haven’t read any of the novels or watched the new Resistance cartoon. The idea of a canon means I feel like I should keep up with those stories on some level, but I just can’t.

I suppose that is a tension born of applying the metaphor of a canon to an open-ended storytelling structure. A closed canon is manageable; you know exactly what you are committing to from the beginning. An open canon, however, invites a similar level of dedication but without defined scope. If the story is the work of a single creator – Tolkien, Lucas, Agatha Christie, etc. – one can have some hope of keeping up; it takes far less time to read a book or watch a film than to create one. But when the storytelling grows exponentially, with spinoffs of spinoffs of spinoffs by more and more storytellers, then the reader/viewer can easily be swamped. How do you navigate that growth?

In terms of Christianity, there is obviously a closed canon which is an invitation to a relationship with a single Creator. At the same time, I suppose there is a possibility of being overwhelmed by the proliferation of supplementary material, programs, service opportunities, etc. Would you agree there is some sort of a parallel there, or am I reaching?

MB: I, too, have completist tendencies, whether it be a favorite musical artist or, in the immediate context of our conversation, Star Wars. I have, to date, collected every story-based novel and comic ever produced (and even some that were “canceled”), with the exception of some material produced overseas and not readily available to U.S. consumers. It is overwhelming, and I must admit to being burned out on many occasions. In fact, before Lucasfilm hit the canon reset button, I was very behind in my reading, although I was aware of the broad strokes of certain series, like the Old Republic novels. This time around, I’ve done a decent job of keeping up with the literature. I’m only about a half-dozen books behind!

Your query about the closed canon of Christianity and its implications for living a life of faith is interesting. As a purely intellectual exercise, I recently finished reading all of the “standard works” of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS) (aka the Mormons) in an effort to better understand one of America’s homegrown religions. During my journey, I discovered that the LDS church has an open canon that is not restricted to their four bodies of written scripture: the King James Version of the Bible, the Book of Mormon, Doctrine and Covenants, and The Pearl of Great Price. Rather, their canon includes all of the church’s officially-sanctioned material, to include speeches that their living prophets – which include the President, the First Presidency (the President and two others), and the Quorum of Twelve Apostles – give at their semi-annual General Conferences. I can imagine that trying to “keep up” with this open-ended canon could put a lot of pressure on someone, especially those with “spiritual completist” tendencies, and even more so if our personal salvation might (hypothetically) be on the line. For example, the LDS institution of polygamy has undergone considerable back-and-forth, beginning with Doctrine and Covenants 101 [1835/1844 versions] (“We believe, that one man should have one wife; and one woman, but one husband“), to Doctrine and Covenants 132 (where Joseph Smith declared plural marriage a “new and an everlasting a covenant; and if ye abide not that covenant, then are ye damned; for no one can reject this covenant and be permitted to enter into my glory”), and then back again with Doctrine and Covenants’ Official Declaration 1 (“We are not teaching polygamy or plural marriage, nor permitting any person to enter into its practice“). It’s hard to know where theology will eventually lead where there are no “manageable” canonical boundaries.

)

)Are you familiar enough with the Star Wars EU that you can comment on whether you think J.J. Abrams & Co. could have created compelling new Star Wars storylines while honoring the canon-that-was?

AW: I see a couple of ways to approach this. For one, I would have been quite content if Lucasfilm/Disney had chosen to adapt some of the EU material into films, such as that initial Timothy Zahn trilogy. That would make it easy to respect the existing EU canon, although it wouldn’t necessarily lead to new storylines. And in 2014, it may have been impractical to tell those specific stories with the original cast.

Telling new stories in the existing EU continuity may have been trickier. I certainly think possibilities existed; you could tell Old Republic stories, next-generation stories with the Solo and Skywalker children or grandchildren, or stories about other corners of the galaxy. I don’t know if J.J. Abrams specifically was the man for that job, as he seems mostly interested in revisiting characters and aspects of the original films. Maybe he could have done a next-generation story, basically picking up where the now-Legends novels had concluded. Of course, leaving a whole era of story untold on the screen could be unsatisfying; not everyone is going to read the books. But the first movie was (retroactively) Episode IV and that worked. So, I think there was definitely a way to rejoin the narrative thread downstream and make it comprehensible for film-only audiences while not contradicting the EU novels.

Readers–what are you thoughts about Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace? What is your experience with the broader universe of Star Wars storytelling? How do you interact with expansive, open-ended narratives? Feel free to join the conversation in the comments. And if you want to watch along, the next film in our festival lineup is I Am Mother; we’ll save a seat for you!

Mike Beidler is a retired U.S. Navy commander whose combination of military aviation experience and Star Wars fandom pedigree launched him, beginning in the mid-’90s, into a decades-long relationship with numerous Star Wars authors. His direct contributions to the Star Wars universe include work on Tom Veitch’s Dark Empire saga, A. C. Crispin’s Han Solo trilogy, and John Whitman’s Galaxy of Fear series. He has, in a galaxy far, far away, worked as a forensic specialist for a Hutt crimelord, studied with the B’omarr monks of Tatooine, and hunted down a bounty or two. He has also written about Star Wars and Blade Runner for Sequart Organization. In this galaxy, however, he lives in northern Virginia with his wife and three children and takes advantage of his daily 45-minute commute to/from the Pentagon to read theology and science fiction. Mike is President of the Washington DC chapter of the American Scientific Affiliation (ASA), a contributing writer to BioLogos, and a member of the both the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) and the National Center for Science Education (NCSE).

Andy has worn many hats in his life. He knows this is a dreadfully clichéd notion, but since it is also literally true he uses it anyway. Among his current metaphorical hats: husband of one wife, father of two teenagers, reader of science fiction and science fact, enthusiast of contemporary symphonic music, and chief science officer. Previous metaphorical hats include: comp bio postdoc, molecular biology grad student, InterVarsity chapter president (that one came with a literal hat), music store clerk, house painter, and mosquito trapper. Among his more unique literal hats: British bobby, captain’s hats (of varying levels of authenticity) of several specific vessels, a deerstalker from 221B Baker St, and a railroad engineer’s cap. His monthly Science in Review is drawn from his weekly Science Corner posts — Wednesdays, 8am (Eastern) on the Emerging Scholars Network Blog. His book Faith across the Multiverse is available from Hendrickson.

Leave a Reply