Do evangelicals use a different political calculus than non-evangelicals in determining which political candidates to support this election season?

At first glance, it appears evangelicals are motivated by a different set of issues than non-evangelicals. However, after factoring for social and political demographics, evangelicals only differ in how they rank three of twenty-one election issues.

Contrary to recent research claiming respondents’ faith predicts the election issues that motivate how they decide which candidates to support, I find evangelicals’ political attitudes are very similar to that of non-evangelicals. While not identical, evangelicals are far less unique from non-evangelicals than (mis)perceived by those inside and outside the Church.

My analysis is based on data about how respondents rank the top issues that determine which political candidate they will support (see here for more details about 2016 National Election Survey the data is sourced from).

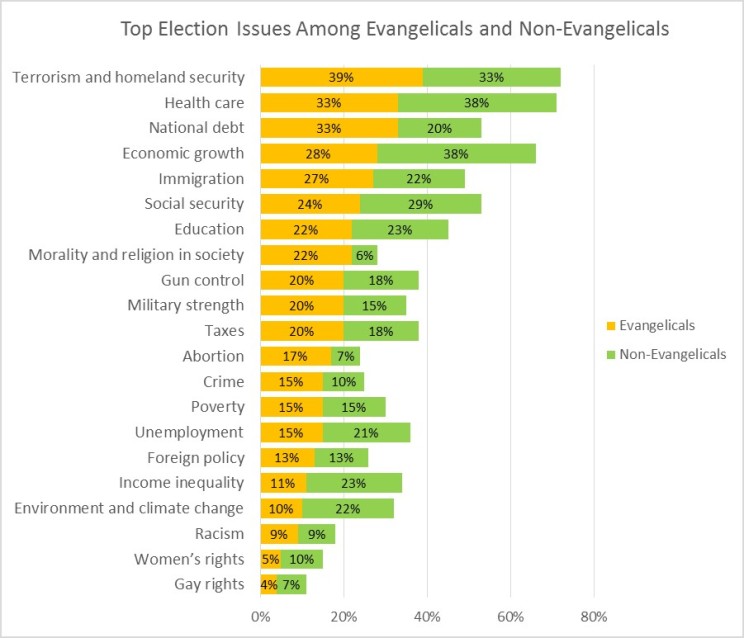

There appear to be differences in the election issues evangelicals rank as most important. 39% of evangelicals rate terrorism and homeland security as a top election issue, compared to 33% of non-evangelicals. Similarly, 33% of evangelicals rate the national debt as an important issue determining what political candidate they will support but only 20% of non-evangelicals do. By contrast, non-evangelicals are more likely to rate health care (38%) and economic growth (38%) as top election issues compared to evangelicals (33% and 28% respectively).

Among issues all voters consider less important, evangelicals and non-evangelicals seem to also have different sets of priorities. Compared to evangelicals, more non-evangelicals rate income inequality (23% versus 11%) and the environment (22% versus 10%) as top election issues. By contrast, more evangelicals rate morality and religion (22% versus 6%) and abortion (17% versus 7%) as top election issues.

But are evangelicals and non-evangelicals really that different in their political calculus?

A more complete analysis of how much evangelicals differ from non-evangelicals must account for respondents’ social and political profile. While evangelical beliefs and practices can have causal power in shaping political attitudes, so can other factors. For example, older people may differ in the types of issues they prioritize compared to younger people. Similarly, political affiliation and ideology can also shape how they rank top election issues.

To calculate adjusted differences, I use logistic regression models that account for whether respondents are evangelicals and their age, gender, ethnicity, education, marital status, party identification, and political ideology.

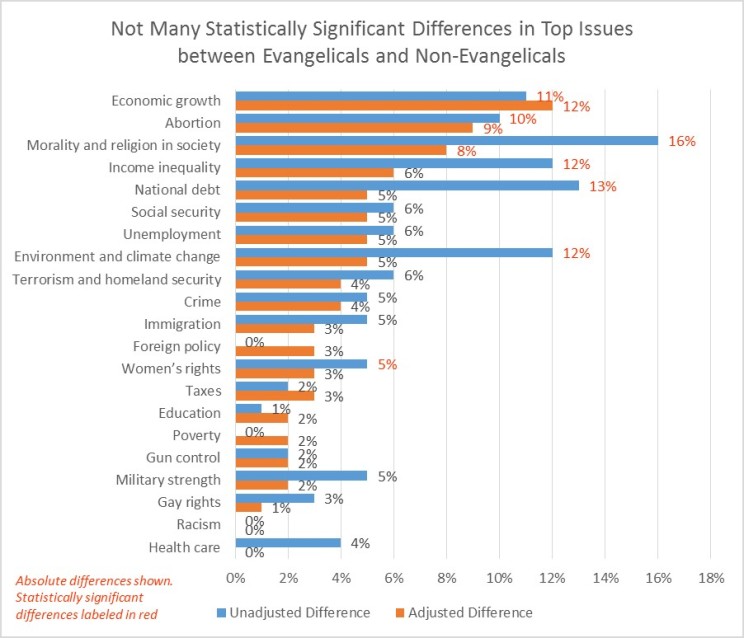

The results, summarized in the chart below, reveal evangelicals’ importance ranking only differ from non-evangelicals in three of twenty-one election issues. After factoring for respondents’ social and political demographics, evangelicals and non-evangelicals differ in how important they rank economic growth, abortion, and morality and religion in society; specifically, evangelicals are more likely to rank abortion and morality as issues determining which political candidates they will support, while non-evangelicals rate economic growth more importantly than evangelicals.

However, across the other eighteen election issues, there are no statistically significant adjusted differences between evangelicals and non-evangelicals. While there are statistically significant unadjusted differences between how evangelicals and non-evangelicals rank income inequality, the national debt, environment and climate change, and women’s rights, adjusted differences are not statistically significant.

Abortion, economic growth, and the role of morality and religion in society are important issues. However, across the full range of election issues, being an evangelical is a poor predictor of how respondents rank whether that issue is an important determinant of which political candidate to support. While evangelical identification only predicts rank importance in three of twenty-one election issues, political ideology is a statistically significant predictor in fourteen issues, age in thirteen issues, and political affiliation in twelve issues.

These findings should bring us pause. While evangelicals need not (and do not) have homogenous political attitudes and worldviews, that evangelicals do not seem to differ from non-evangelicals in the issues motivating our political calculus should prompt us to (re)consider if there are otherwise overlooked priorities and causes we should advocating. We should also be compelled to greater reflection of how our evangelical beliefs and identities interact, engage, and transform our cultural belongings, party affiliation, and political ideologies.

In Romans 12:2, we are called to not “be conformed to this world, but be transformed by the renewal of your mind, that by testing you may discern what is the will of God, what is good and acceptable and perfect.” Let us not passively adopt the political priorities and motivations of those like us. Instead, let us continually and humbly seek God’s wisdom in discerning how His Gospel should shape our attitudes, our beliefs, our worldviews, and yes, even our politics.

Update (4/25, 11 am): Not Many Statistically Significant Differences in Top Issues between Evangelicals and Non-Evangelicals (Chart).

Joshua Su-Ya Wu is a husband, father, pastor’s kid, and social scientist seeking to faithfully reflect Christ in all aspects of his life. He has a doctorate in Political Science from The Ohio State University, works in analytics and data science, and writes about data analytics at Reasonable Research and the intersection of faith and culture at Stuff I Didn’t Learn in Church. He currently lives in Rochester New York with his wife and two kids, and can be reached on Linkedin or on Facebook

Leave a Reply