This is the fourth in a 5 week series exploring the relationship between miracles and science. See this Science Corner post for a prelude, this post for part 1, this post for part 2, and this post for part 3.

Three weeks ago, we started our exploration of miracles by looking at how human monarchs influence our perception of God as king. Then, we considered the metaphor of the law as it relates to our understanding of the natural world, and explored how the ideas of will and of grace might be used to frame a different understanding. Now I want to go back to Scripture to try tie all these ideas together; since Palm Sunday is approaching, it seems fitting to look at the triumphal entry, with Jesus at his most regal.

In my reading of 1 Samuel 8, I proposed that God was concerned about how our human examples of kings might be used to make incorrect inferences about God’s nature as king. That doesn’t necessarily mean all kings and all regal imagery need be discarded when we seek to know God. We saw that David had many qualities God endorsed. Solomon made several contributions to the Bible, and several other kings of Israel and later Judah provide positive examples of how a king might behave. We don’t need to eliminate the metaphor of a king entirely, we just need to be discerning about which kings we look to. And what better king to consider than Jesus himself?

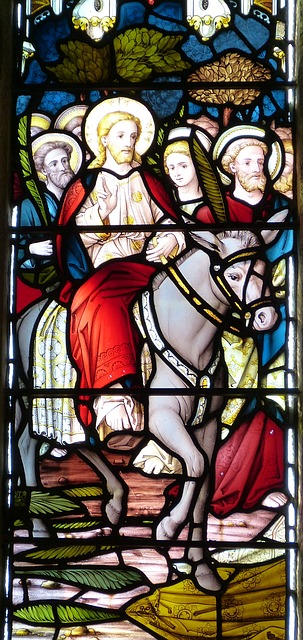

After years of avoiding most noble trappings, Jesus makes his final arrival into Jerusalem with great fanfare. The people give him the royal treatment, perhaps hoping he would be a liberator or reformer. His arrival is heralded, and his path is prepared with cloaks and fronds to make his ride as smooth as possible. These were common practices when dealing with nobility, and are anticipated throughout the Bible, from Old Testament prophecies to the angels’ announcement of Jesus’ birth. These preparations are not orchestrated by Jesus; he allows the people to respond to his arrival as they see fit.

Of all the elements of this triumphal entry, there is only one detail that Jesus arranges specifically. He indicates that he wants to ride on a donkey, and even provides instructions on where to find it. As I understand it, there is some precedent for this choice; riding a donkey was a symbol of peace, whereas as horse would have represented militarism. Why these associations? Certainly horses were used in military contexts. Riding a horse is also a sign of power — “I have broken this horse and bent his will to my own, and I will do the same to you.” A donkey that had never been ridden may not have provided the same visual demonstration of the rider’s power.

Of all the Gospel accounts of this arrival, Mark adds an interesting detail about returning the donkey once Jesus is through with it. Since this element only appears in this one version, it may not warrant any strong inference. Still, it is consistent with the image of Jesus making as few demands as possible, rather than trying to demonstrate his authority by enforcing his will to the greatest possible extent.

Luke provides another glimpse of Jesus declining to assert power over the situation. Some of the Pharisees don’t like what is happening and ask Jesus to get his followers under control, and Jesus declines. There are several reasons why he might have done so, not least of which being that he had little to object to about their behavior. What I find particular fascinating is what he says about why he won’t stop the crowds. He says that if the people are silent, the rocks will cry out. What I see in that is a description of the kind of robustness, or grace, that we talked about last time. The individual participants had the freedom to praise Jesus or not (Jesus also does not insist that the Pharisees join in the chorus), and yet the overall result of exaltation would be achieved no matter what.

The triumphal entry ultimately provides a complex picture of a regal Jesus. He doesn’t completely reject the desire of the people to relate to him as they would one of noble or royal standing. Even the donkey connects Jesus to a prophecy from Zechariah about Jerusalem’s king. At the same time, that choice and others subvert certain expectations about how a king would behave.

In the following days Jesus spent in and around Jerusalem, issues of authority, power, and government arise again and again in Jesus’ actions, his teachings, and the questions and requests that various parties bring to him. Jesus cleanses the temple in what seems like a demonstration of priestly or even divine, rather than political, authority. When asked about taxes, he sidesteps an opportunity to undermine the authority of the Roman government some hoped he would overthrow. He raises questions about our usual understanding of the power of wealth in the teaching about the widow’s mite. He displays what must have seemed to be a divine power over nature by cursing the fig tree. Throughout the week, he apparently never misses an opportunity to confound expectations and clarify what roles he would and would not be filling in the lives of his followers.

As we now know, that week was building to one final subversion of expectations. As we saw back in 1 Samuel 8, one of God’s primary warnings about kings was their tendency to conscript sons to serve in their armies. The implication is that a king will sacrifice the life of your sons in order to secure his legacy. Finally it is revealed exactly why God didn’t want to be associated with that practice. God’s supreme act as king would be to sacrifice the life of his own son to secure the legacy of everyone.

Of course, the story doesn’t end there. What makes it truly remarkable is the event yet to come, the resurrection. If there is such a thing as a miracle, surely returning from the dead would qualify. So just what is a miracle then?

Andy has worn many hats in his life. He knows this is a dreadfully clichéd notion, but since it is also literally true he uses it anyway. Among his current metaphorical hats: husband of one wife, father of two teenagers, reader of science fiction and science fact, enthusiast of contemporary symphonic music, and chief science officer. Previous metaphorical hats include: comp bio postdoc, molecular biology grad student, InterVarsity chapter president (that one came with a literal hat), music store clerk, house painter, and mosquito trapper. Among his more unique literal hats: British bobby, captain’s hats (of varying levels of authenticity) of several specific vessels, a deerstalker from 221B Baker St, and a railroad engineer’s cap. His monthly Science in Review is drawn from his weekly Science Corner posts — Wednesdays, 8am (Eastern) on the Emerging Scholars Network Blog. His book Faith across the Multiverse is available from Hendrickson.

Leave a Reply