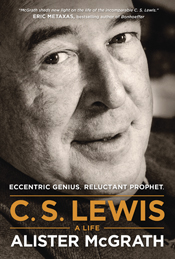

Review of Alister McGrath, C.S. Lewis — A Life: Eccentric Genius, Reluctant Prophet (Carol Stream, IL: Tyndale House, 2013) for the Emerging Scholars Network (ESN). Part I. Click here for Part II.

Alister McGrath is, like many of us, a fan of C.S. Lewis who never had the opportunity to study under or even met him. Although McGrath probably shares more similarities with Lewis than you or I, as someone raised in the same part of Ireland as Lewis and educated in Oxford, he thinks this distance will allow him the opportunity to do what previous biographers have not been able to do, objectively write about Lewis as someone who lacks personal connection. With this as his goal, he sets out to write a definitive biography of Lewis. As with any piece of academic writing, there are going to be good and not-so-good aspects of the work. There is no work which will meet with full approval of the entire academic community and McGrath’s biography of Lewis is no different. There are aspects of this biography that will undoubtedly please many and there are some issues which have the potential to change the nature of the discussion about Lewis for a long time. Ultimately however, I believe that McGrath’s biography, while certainly important, has several aspects to it which make it still lacking. There are many ways to come at a review of a new book, but since I am writing for ESN, I decided to group things under two broad categories which I think will be helpful for grad student readers considering how to spend their meager time and resources.

Why you should buy/read this book

As I read the book for the first time (full disclosure – the first time I “read” it was listening to the book as I drove back and forth to Washington D.C.) there were several things that stood out to me as especially helpful, particularly as an evangelical in America who is also working toward a life in academia. The first was the final chapter of the book which recounts the re-introduction and reception of Lewis in America after his death and the fallow years where Lewis was nearly forgotten in his homeland. McGrath gives several reasons for this shift in interest to Lewis, but two stand out to me. First, he says, “Engaging both heart and mind, Lewis opened up the intellectual and imaginative depths of the Christian faith like nobody else” (369). Second, he points to Lewis’ emphasis on ‘mere Christianity’ as fitting into a particularly American ecclesial concept which was devoid of the denominational loyalties compared to the British context with its connection between State and Church. McGrath makes a connection between Lewis’ rise to fame in the early 1960’s as coinciding with an American cultural and church context which was dropping traditional denominational connections (cf. 370). He also looks at the reception Lewis had among American Catholics, particularly through the work of Peter Kreeft and Avery Cardinal Dulles, in connection to Lewis’ status as an outsider to the American religious scene and his mere Christian emphasis. It is worth noting that Kreeft is a Catholic convert, and a Lewis scholar, who has published several books on Lewis’ thought. Among his published works is a book that ESN readers might find interesting, Between Heaven and Hell (InterVarsity Press, 2008) which is a fictionalized account of a meeting between Lewis, John Kennedy and Aldous Huxley after they all died on the same day in 1963.

McGrath has a section that is dedicated to specifically to the American evangelical reception of Lewis’ works, dating back to the origins of the modern American evangelical situation when people like Billy Graham and Carl F.H. Henry were trying to distinguish themselves from the fundamentalists and the anti-intellectual tendency which was so often pervasive after the battle for the Bible in the earlier part of the twentieth century. Henry even invited Lewis in the mid-1950’s to write some apologetic pieces for Christianity Today which Lewis ultimately declined. However, the main contributing factor to the evangelical reception of Lewis’ Mere Christianity as an important apologetic work is because he based “his apologetic approach on general principles, fine observation, and an appeal to shared human experience” (373). He also singled out evangelical student groups like InterVarsity and their use of Mere Christianity as well as Lewis’ other apologetic works in their student ministries as an important factor in the evangelical reception of Lewis as an apologist. As evidence that McGrath is correct, consider the importance of Mere Christianity in American evangelicalism in light of its second place finish in last year’s “Best Christian Book” sponsored by ESN. Evangelicals, especially educated evangelicals, seem to have adopted Lewis as one of their own, incorporating his “conversion” as part of their own understanding of what it means to be “born-again” (373)[1].

I think that any book that is worth its academic salt will not necessarily answer every question but points to avenues which leave you wanting more, or with the idea that a particular angle in a story needs more research. This section on the evangelicals left me with just that feeling. For instance, Lewis is quite open to a universe and mankind that has largely come down to us through evolutionary means, but this is certainly not universally accepted in the evangelical community. Lewis holds to many doctrinal viewpoints which evangelicals would find problematic, including his lack of stance on the atonement issue, his views on the afterlife and his understanding of limbo, to name just a few. But McGrath is right, evangelicals certainly are very comfortable with Lewis as one of their own[2]. McGrath points out that Lewis has by no means been universally accepted, but it seems like there is more to this story as well; McGrath only giving one counter-example of the acceptance of Lewis. This is one place where I think there is might be more nuance to the situation than McGrath presents. Specifically I wonder if there has been a kind of acceptable corpus which includes only certain aspects of Lewis (Narnia, Surprised by Joy and Mere Christianity in particular), but the greater corpus of Lewis’ writings have been neglected by evangelicals, whether intentional or not.

The other major aspect of the book which I thought was very good and will be of particular interest for ESN readers is McGrath’s treatment of Lewis’ academic life as an Oxford don. I think the basic details of Lewis’ academic life as a student and Lewis’ status as a professor at Oxford and then at Cambridge is pretty well-known. However, the academic life of Lewis, including some of the struggles that he faced at Oxford in his professional career, were opened in a way that I found very intriguing and I think ESN readers will find very relatable to their own academic careers.

First, McGrath recounts Lewis’ concerns about securing an academic teaching position upon graduation. It is perhaps easy to forget that Lewis, brilliant though he was, was at one time in the exact same position that all graduate students find themselves – he was concerned about money and he was worried about finding an academic job after graduation, which in post-war England was difficult. In an effort to make himself more marketable, Lewis decided to take a second degree from Oxford, this time in English literature. Even after these steps, he ended up taking a yearlong temporary teaching position in philosophy before he was elected as a fellow at Magdalen College. Finding part-time work as a grader, struggling to make the little money that he had cover expenses are all experiences to which grad students can relate.

Second, McGrath brings to the surface the struggles that Lewis had in his professional career at Oxford. It is perhaps an unknown aspect to Lewis’ life for many (myself included) that Lewis was not well-received by many in his own College, let alone by his peers in the English department at Oxford. This was due to several reasons, but two seemed especially important to highlight. First, many saw Lewis as somewhat of an academic lightweight because of his work on popular writing. McGrath points out that “many of his academic colleagues came to believe that he had sold his academic birthright for a populist pottage” (242). This was especially evident perhaps when Lewis was passed over several times for promotion to a professorial chair. Partially this was due to Lewis’ popularity and partly this was due to Lewis’ failure to be political in the way that he dealt with issues like expanding the English literature curriculum to include the Victorian period and higher degrees being offered at Oxford (247-250). McGrath says “the real roots of the problem were Lewis’s popular acclaim and his seeming disregard for the norms of traditional academic scholarship” (247). Lewis, the popular Christian apologist and fiction writer, was marginalized in his own academic culture. As McGrath points out, there was some truth to this critique of Lewis – from his publication of The Preface to Paradise Lost (1942) he published nothing of serious academic scholarship until his work on medieval literature in 1954. Even in Lewis’ academic world, publish or die was the academic norm. In the end, Lewis had to leave Oxford to receive a professorship, at the other medieval university in England, Cambridge, which he held until he resigned due to health concerns shortly before his death.

Tomorrow: Part II, focused upon Things which I felt did not work . . .

Update: 1/16/2014 (2:09 pm)

Notes

- See also Michael Ward’s recent piece in Christianity Today (Nov 2013), “How Lewis Lit the Way to Better Apologetics”, for another take on Lewis’ influence among evangelicals. ↩

- In a recent interview, Tim Keller and John Piper declared that Lewis was evangelical, but George MacDonald was not even a Christian because of his views on the afterlife and his universalism. However I think Lewis is much closer to MacDonald than he is to Piper on the issue of hell and salvation. ↩

I am a PhD student in theology at Catholic University of America in Washington, DC. I am studying the theology of John Williamson Nevin, who taught in the seminary of the German Reformed Church in America in the mid-nineteenth century. He was also the president of Franklin and Marshall College and a friend to James Buchanan, the 15th president of the United States. I am currently a teaching fellow at CUA, teaching undergraduate theology and Church History classes. My goal is to teach at a college or university after completing my degree program. I am also the current vice-president of the graduate student association at CUA. Before life as a grad student (if that were an acronym it would be BLaaGS) I was a teacher and principal in secondary education at various Christian schools in the Northeast. My family and I currently live in Hagerstown, MD.

Leave a Reply