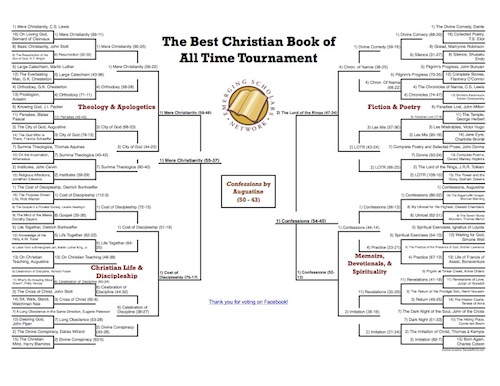

No, I’m not creating a Dead Theologians Society Reading List, another version of The Best Christian Book of All Time March Madness, or even another book review/discussion series per se. Instead I’m in the process of completing the final exam for my summer class on Christian Devotional Classics (Evangelical Seminary).

Really, a final exam? Yes, Laurie Mellinger, Ph.D. (Associate Professor of Spiritual Formation and Christian Theology, Dean of Academic Programs), has us wrap-up the roundtable presentation/discussion course with a “curriculum project” which seek

to relate the major texts of the course to a 21st-century audience by ‘bridging the hermeneutical gap’ between past and present. . . . [including] all of the major devotional classics in the course, with evidence of knowledge of the historical and theological context in which they were written. It should also include commentary on and application of the readings to a contemporary audience in a specified ministry context.

What better place to attempt such a task than via a blog series for the Emerging Scholars Network 🙂 As some of you know I started picking away at the project as soon as the class began by creating a daily reflection posts on the Emerging Scholars Network Facebook Wall. Today I’ll begin the blog series by introducing the devotional material I have already posted on Thomas Merton’s Wisdom of the Desert: Sayings of the Desert Fathers of the Fourth Century (Boston: Shambhala Publications, 2004) with a brief biography of Thomas Merton.* Merton helps us step into the fourth century where among a few there was a passion to grow in Christ-likeness by separation from not only the world, but also the growing institutionalization of the church. As you may remember, Constantine the Great ruled as the Roman Emperor from 306–337. The First Council of Nicaea was held in 325, giving the church the official position of deity of Christ. Christianity officially became the state church of the Roman Empire in 380.

In my next post I’ll take a step back and explore “What is a Christian Devotional Classic?” Along the way, please share your insights so that I can improve the material. Yes, please consider this a work in progress which can be enjoyed along the way. To God be the glory!

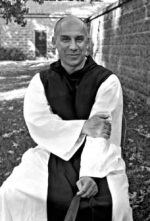

Thomas Merton (1915 – 1968)

Thomas Merton‘s “Preface” to Wisdom of the Desert: Sayings of the Desert Fathers of the Fourth Century was significant in my framing of the material by/about the Desert Fathers. Furthermore, the Preface leads me to desire to dig deeper in the life and perspective not only of the Desert Fathers and Mothers, but also Thomas Merton. With regard to Merton, what drew him to a hermitage in order to escape the corruption of the social world and achieve “salvation” . . . enter a deep mystical love relationship with God through a life of solitude? In what manner does he understand “love” to be the most important aspect of his spiritual life, spilling out into all of one’s relationships and actions (as individuals and communities)? What led him to find commonality with Zen Buddhism later in life? How and why did Merton continue to maintain the discipline of writing and study, even sensing a call to travel to share his thoughts when committed to a life of solitude and separation from the world?

As a 20th century figure, Merton’s not too distant from us. But what an encouraged that he engaged a number of the significant events, movements, and trends of the 20th century with a passion. Below is a glimpse of Merton’s life and some reminders of his context. Note: I borrow from and build upon the chronology posted by the Thomas Merton Center at Bellarmine University (Accessed 8/8/2013).

- 1915: Born in France (Prades, Pyrénées-Orientales), but his family quickly left to live with his mother’s family in New York due to World War I.

- “The War to End all Wars” failed to do such. The recurrence of war was significant in Merton’s life.

- 1918: Thomas’ brother John Paul born.

- 1921: His mother Ruth Jenkins (artist from USA) dies from cancer

- Wrestled with his father’s (Owen Merton, artist from New Zealand) travels, illnesses, and various other relationships. Some of this time he lived with his mother’s parents, then later with his father’s relatives in England and his father in France. Schooling in France, then England (including Cambridge). As an itinerant artist his father had difficulty earning money even during the “Roaring 20’s” before the Great Depression.

- 1931: His father passes away due to a brain tumor. Merton cared for by friends and relatives in England, where he continued his education.

- 1933: In a trip to Rome, he had a mystical experience leading him to call out (pray) for deliverance from the emptiness/darkness he felt. Also, he glimpsed and began to have interest in possibly becoming a Trappist monk.

- Note: I’m really interested in reading about this in The Seven Storey Mountain. I’ve added the autobiography to my reading queue.

- 1935: Entered Columbia University, NYC. Briefly explored communism, which was on the rise as the Soviet Union continued to flourish during the Great Depression which affected much of the global economic system.

- 1938: Received into the Catholic Church at Corpus Christi Church after reading a number of books, visiting mass, but most importantly reading Gerard Manley Hopkins’ conversion to Catholicism.

- Shortly afterward he became involved in Catholic Action.

- 1940 – 1941: Taught English at St. Bonaventure College. Note: American involvement in World War II (1940-1945)

- 1941: Entered the Abbey of Our Lady of Gethsemani, Kentucky. This community of monks belongs to the Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance (Trappists), the most ascetic Roman Catholic monastic order.

- InterVarsity Christian Fellowship/USA was incorporated. For more of the ministry’s history click here.

- 1942: John Paul visited Thomas at the monastery before entering World War II. John Paul was “lost at sea” as a pilot in 1943.

- 1948: Publication of best-seller autobiography, The Seven Storey Mountain and What Are These Wounds? He sold over one million copies and has been translated into over fifteen languages.

- Merton wrote over sixty other books and hundreds of poems and articles on topics ranging from monastic spirituality to civil rights, nonviolence, and the nuclear arms race. . . . — http://merton.org/chrono.aspx.

- Note: It 1948 Harold Ockenga brought neo-evangelicalism to the table, inspiring a new generation of Evangelicals to engage culture and other partnership across denominations, including with Roman Catholics.

Harold John Ockenga, pioneer of neo-Evangelicalism. Photo from Ockenga Institute at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary,

- 1960’s: The conscience of the peace movement. “Referring to race and peace as the two most urgent issues of our time, Merton was a strong supporter of the nonviolent civil rights movement, which he called ‘certainly the greatest example of Christian faith in action in the social history of the United States.’ For his social activism Merton endured severe criticism, from Catholics and non-Catholics alike, who assailed his political writings as unbecoming of a monk.– http://merton.org/chrono.aspx.

- Merton’s abbots were the ones who prodded him and encouraged him to write. And finally in 1968 one let him off-site.

- In 1960, John F. Kennedy became the first Roman Catholic President of the United States of America.

- In the 1960’s the Charismatic movement took off in wider Evangelicalism.

- 1962 – 1965: Vatican II assembled for the Roman Catholic Church to address significant concerns and next steps.

- 1965 – 1968 – Lived as a hermit on the grounds of the monastery

- 1968: “After several meetings with Merton during the American monk’s trip to the Far East in 1968, the Dalai Lama praised him as having a more profound understanding of Buddhism than any other Christian he had known. It was during this trip to a conference on East-West monastic dialogue that Merton died, in Bangkok on December 10, 1968, the victim of an accidental electrocution. The date marked the twenty-seventh anniversary of his entrance to Gethsemani.” — http://merton.org/chrono.aspx

Along the way Merton explored Anglicanism, agnosticism, communism, Zen Buddhism (later in life), East-West dialogue (later in life). Breathe.

In reviewing Merton’s life, the need to take breath and find some space for solitude struck me in a deep way. His early years were marked by a lot of familial instability and cross-cultural travel. In Christ he found a resting place and among the Desert Fathers of the fourth century he found great inspiration of how to continue to dwell in Christ.

But unlike many who sought solitude, he could not keep quiet. As such, it was from his place of quiet that he spoke into the 20th Century’s violence (Cold War, Korea, Cuban Missile Crises, Vietnam War), social concerns (peace, simplicity, racism, social equality), desire to find oneself (Note: many turned to monastic life due to Merton’s inspirational writing), and yearning for interfaith dialogue. Some consider Thomas Merton (1915-1968) the most influential American Catholic author of the twentieth century. Whether or not that is case, this is much to consider about his conversion, wrestling with social engagement as a Christian, and interfaith dialogue/practice (worthy of a future post).

What do the desert fathers and mothers have to say to us today?

1. Salvation. “In those days* men had become keenly conscious of the strictly individual character of ‘salvation.’ Society — which meant pagan society, limited by the horizons and prospects of life ‘in this world’ — was regarded by them as a shipwreck from which each single individual man had to swim for his life. We need not stop here to discuss the fairness of this view; what matters is to remember that it was a fact. These were men who believed that to let oneself drift along, passively accepting the tenets and values of what they knew as society, was purely and simply a disaster. The fact that the Emperor was now Christian and that the ‘world’ was coming to know the Cross as a sign of temporal power only strengthened them in their resolve.” — Thomas Merton. “Wisdom of the Desert: Sayings of the Desert Fathers of the Fourth Century” (Boston: Shambhala Publications, 2004, 1-2).

1. Salvation. “In those days* men had become keenly conscious of the strictly individual character of ‘salvation.’ Society — which meant pagan society, limited by the horizons and prospects of life ‘in this world’ — was regarded by them as a shipwreck from which each single individual man had to swim for his life. We need not stop here to discuss the fairness of this view; what matters is to remember that it was a fact. These were men who believed that to let oneself drift along, passively accepting the tenets and values of what they knew as society, was purely and simply a disaster. The fact that the Emperor was now Christian and that the ‘world’ was coming to know the Cross as a sign of temporal power only strengthened them in their resolve.” — Thomas Merton. “Wisdom of the Desert: Sayings of the Desert Fathers of the Fourth Century” (Boston: Shambhala Publications, 2004, 1-2).

For Deeper Reflection: Do we likewise live in such a time/place? If so, how do we/you respond? If not, how do you distinguish our time/place from the Eastern Mediterranean world of the 4th Century?

*”In 4th century A.D. the deserts of Egypt, Palestine, Arabia, and Persia . . .”

2. “What the [Desert] Fathers [and Mothers] sought most of all was their own true self, in Christ. And in order to do this, they had to reject completely the false, formal self, fabricated under social compulsion in ‘the world.’ They sought a way to God that was uncharted and freely chosen, not inherited from others who had mapped it out beforehand. They sought a God whom they alone could find, not one who was ‘given’ in a set, stereotyped form by somebody else. Not that they rejected any of the dogmatic formulas of the Christian faith: they accepted and clung to them in their simplest and most elementary shape. But they were slow (at least in the beginning, in the time of their primitive wisdom) to get involved in theological controversy. Their flight to the arid horizons of the desert meant also a refusal to be content with arguments, concepts, and technical verbiage.” — 6-7.

For Deeper Reflection: Do you seek your own true self in Christ? Is there something unique about doing such in the communal context of higher education? How do you balance what has been passed down to you with coming to know God personally and as part of the Body of Christ? Do you cling to the dogmatic formulas of the Christian faith in in their simplest and most elementary shape — if so, how would you ‘simply’ define the Christian faith? How does one resist an argumentative approach to one’s faith and vocation?

3. Love. “Love in fact is the spiritual life, and without it all the other exercises of the spirit, however lofty, are emptied of content and become mere illusions. The more lofty they are, the more dangerous the illusion. . . . Love demands a complete inner transformation — for without this we cannot possibly come to identify ourselves with our brother. We have to become, in some sense, the person we love. And this involves a kind of death of our own being, our own self. No matter how hard we try, we resist this death: we fight back with anger, with recriminations, with demands, with ultimatums. We seek any convenient excuse to break off and give up the difficult task. But in these ‘Verba Seniorum’ we read of Abbot Ammonas, who spent fourteen years praying to overcome anger, or rather, more significantly, to be delivered from it. We read of Abbot Serapion, who sold his last book, a copy of the Gospels, and gave the money to the poor thus selling ‘the very words which told him to sell all and give to the poor.'” — 26-28.

For Deeper Reflection: Do you agree with the necessity of love to “the exercises of the spirit” and inner transformation? Have you found the ability to love (even “become”) those above, below and at the same level as you in the “academic chain of being” — even those unable and/or not desiring to participate in higher ed? Do you, as I, long to die to one’s self (including natural tendencies such as anger) and find it hard to believe that one may embody one’s faith by selling one’s last book(!)?

4. Pulling the world to safety. “The simple men who lived their lives out to a good old age among the rocks and sands only did so because they had come into the desert to be themselves, their ordinary selves, and to forget a world that divided them from themselves. There can be no other valid reason for seeking solitude or for leaving the world. And thus to leave, the world, is in fact, to help save it in saving oneself. This is the final point, and it is an important one. The Coptic hermits who left the world as though escaping from a wreck, did not merely intend to save themselves. They knew that they were helpless to do any good for others as long as they floundered about in the wreckage. But once they got a foothold on solid ground, things were different. Then they had not only the power but even the obligation to pull the whole world to safety after them. . . . We cannot do exactly what they did. But we must be as thorough and as ruthless in our determination to break all spiritual chains, and cast off the domination of alien compulsions, to find our true selves, to discover and develop our inalienable spiritual liberty and use it to build, on earth, the Kingdom of God. This is not the place in which to speculate what our great and mysterious vocation might involve. That is still unknown. Let it suffice for me to say that we need to learn from these men of the fourth century how to ignore prejudice, defy compulsion and strike out fearlessly into the unknown.” — 35-36.

For Deeper Reflection: How do you address a world (at times jobs/responsibilities) that divide you from yourself and your calling — leading to a compartmentalism which threatens Christ being at the center/core of all of your life, including your vocation? How have you found spiritual disciplines such as prayer, silent reflection/meditation upon Scripture, silence, rest, and solitude a blessing? Are you ready to learn from men and women of the 4th Century in how to “to ignore prejudice, defy compulsion and strike out fearlessly into the unknown?”

5. A trader in words. “A certain brother came, once, to Abbot Theodore of Pherme, and spent three days begging him to let him hear a word. The Abbot however did not answer him, and he went off sad. So a disciple said to Abbot Theodore: Father, why did you not speak to him? Now he has gone off sad! The elder replied: Believe me, I spoke no word to him because he is a trader in words and seeks to glory in the words of another.” — 56-57.

For Deeper Reflection: In higher education, do we find ourselves surrounded not only by “traders of words,” but also by those who desire to feed those who “trade words.” Giving it further thought, I wonder if “the academic chain of being,” encourages us to glory in our own words instead of receiving those of others*.

If “a trader in words” came to you today, would you be able to resist for the benefit of both participants in “the conversation”? If so, for how long? I doubt I could last long. As you may guess I am only beginning to learn the value of teaching lessons through silence, in particular a caring silence.

6. Responding to destruction. “There were two brother monks living together in a cell and their humility and patience was praised by many of the Fathers. A certain holy man, hearing of this, wanted to test them and see if they possessed true and perfect humility. So he came to visit them. They received him with joy, and all together they said their prayers and their psalms, as usual. Then the visitor went outside the cell and saw their little garden, where they grew their vegetables. Seizing his stick, he rushed in with all his might and began to destroy every plant in sight so that soon there was nothing left at all. Seeing him the two brothers said not one word. They did not even show sad or troubled faces. Coming back into the cell they finished their prayers for Vespers, and paid him honour, saying: Sir, if you like, we can get one cabbage that is left, and cook it and eat it, for now it is time to eat. Then the elder fell down before them, saying: I give thanks to my God, for I see the Holy Spirit rests in you.” — Thomas Merton. “Wisdom of the Desert: Sayings of the Desert Fathers of the Fourth Century” –113-114.

For Deeper Reflection: Are Christ followers known for humility and patience in your department/discipline, on your campus, across higher education? Have you seen Christ followers tested in their Christ-likeness, even by other Christ followers? If so, how have they responded?How would you respond if someone smashed your research lab, books, computer, instruments, projects . . . what if the smashing occurred by words or lack of recognition/tenure? I pray that the Holy Spirit may truly be seen to rest upon you and all of the people of God called to be present in higher education as Christ’s ambassadors today, tomorrow, and for years to come. To God be the glory!

7. Evil behaviour injures. According to Syncletica [a Desert Mother], “It is dangerous for anyone to teach who has not first been trained in the ‘practical’ life. For if someone who owns a ruined house receives guests there, he does them harm because of the dilapidation of his dwelling. It is the same in the case of someone who has not first built an interior dwelling; he causes loss to those who come. By words one may convert them to salvation, but by evil behaviour, one injures them.'” — Benedicta Ward, translator. “The Sayings of the Desert Fathers: The Alphabetical Collection.” (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Pub, 1975, 1984, 233). Note: Yes, this is a bonus, providing an additional piece beyond Merton.

For Deeper Reflection: How much is the ‘practical’ life considered an important aspect of higher education, of one’s local congregation, of your own daily interactions? How true that words and behaviour are to complement one-another and testify to the reality of the Kingdom of God. We may be able to teach and train another in a particular subject, but does our practice of the subject bless those we have been called to serve? What is reflected in the ‘house’ of one’s department, campus, discipline, local assembly, fellowship?

Join me in praying that the fruit of the Spirit will truly be evident in our ‘houses’ today, tomorrow . . . To God be the glory!

————-

*Added request (8/17/2013, 11:01 PM): Please email me know if you use the second section to stimulate campus discussion (e.g., brown bag lunch discussion group). I am particularly interested in suggestions on revisions for use in that context.

Tom enjoys daily conversations regarding living out the Biblical Story with his wife Theresa and their four girls, around the block, at Elizabethtown Brethren in Christ Church (where he teaches adult electives and co-leads a small group), among healthcare professionals as the Northeast Regional Director for the Christian Medical & Dental Associations (CMDA), and in higher ed as a volunteer with the Emerging Scholars Network (ESN). For a number of years, the Christian Medical Society / CMDA at Penn State College of Medicine was the hub of his ministry with CMDA. Note: Tom served with InterVarsity Christian Fellowship / USA for 20+ years, including 6+ years as the Associate Director of ESN. He has written for the ESN blog from its launch in August 2008. He has studied Biology (B.S.), Higher Education (M.A.), Spiritual Direction (Certificate), Spiritual Formation (M.A.R.), Ministry to Emerging Generations (D.Min.). To God be the glory!

Leave a Reply