The essay “Evolution and Existentialism, an Intellectual Odd Couple” by David Barash proceeds from the premise that evolution and existentialism appear to have contradictory answers about the meaning of life, and then attempts to reconcile them. I don’t feel strongly about the conclusion, but I do find the premise to be faulty, for the reason that evolution does not tell us about the meaning of anything. If it does not speak to the question of meaning, then it cannot conflict with any particular framework that does offer meaning.

Why do I say evolution does not speak to meaning? Mainly because I understand meaning to be extrinsic, rather than intrinsic. Evolution describes a sequence of events and a mechanism for how they came about. The accuracy and usefulness of that description can be discussed within the scientific framework. But what it means, if anything, is an entirely independent question, and it can be answered from any number of perspectives.

Meaning as an extrinsic property follows partly from my understanding of the work of two mathematicians: Kurt Gödel and Claude Shannon. Gödel worked in an era when paradoxes and philosophical questions threatened the foundation of mathematics. Some mathematicians believed we just needed a more precise, systematic framework for mathematics; then we could decide the truth of all mathematical propositions. Gödel proved the opposite — any system sufficiently expressive to represent the mathematical propositions of interest can be used to create propositions that cannot be determined to be true or false within that system. In other words, by attributing meaning to numbers, you introduce the possibility for paradox and ambiguity. There is no perfectly consistent and complete meaning that could then be considered intrinsic.

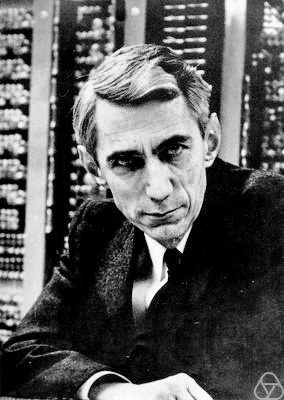

This is consistent with the work of Claude Shannon, who developed the field of information theory. He showed that it was possible to quantify the information content of a message, but this measurement was complete agnostic of the meaning of the message. Thus, one could transmit information from one place to another, but if the parties on both ends did not agree on the meaning, then communication was not possible. Meaning had to be supplied extrinsically to the information.

And really, isn’t this a Biblical principle as well? Consider Mark 4:12

so that although they look they may look but not see,

and although they hear they may hear but not understand

So too, no one knows the things of God except the Spirit of God

and even 1 Corinthians 14:27-28

If someone speaks in a tongue, it should be two, or at the most three, one after the other, and someone must interpret. But if there is no interpreter, he should be silent in the church. Let him speak to himself and to God.

In fact, much of the work of the Holy Spirit as described in Scriptures seems to be making it possible for us to interpret the meaning that God intended in His messages to us; without that guidance, they would be meaningless words.

So, then, what does evolution mean? Let’s consider some common proposals. For example, doesn’t it tell us everything is random? Not really. The process of natural selection does requires variation. And those variations (mutations) are produced by what scientists consider random processes. But there are well-understood mechanisms by which mutations are introduced, and any given mutation comes about via one particular mechanisms. It’s just that we can’t observe those mechanisms directly in all places at all times, and so we can’t say exactly when or where mutations will occur; we can only make statements about their behavior in aggregate. Describing them as random is then a statement about the limits of our observational abilities, not about meaning.

What about the idea that evolution tells us all that matters are our genes? I would say the only thing that matters to evolution is your genes; that’s what it studies and so that’s what it can make statements about. And even that’s an oversimplification. Modern evolutionary science acknowledges that we inherit more than a genome, and that natural selection operates on more than DNA. We are capable of learning that far exceeds what is encoded in our genes, and we pass that knowledge and wisdom along to our children and also our peers. Ideas and cultural developments can be subject to selection processes. Beyond all of that, there is the reality that qualities which are subject to evolution do not represent the full extent of all ontologically valid entities.

OK, but surely it means something that we are descended from monkeys. Well, first of all, the theory of common descent doesn’t say we are descended from monkeys; rather that we and monkeys share an ancestor in common. But that does not negate the distinctiveness of humans from monkeys. Perhaps if we take a step further back, the situation becomes more clear. Common descent also says that we share a common ancestor with bacteria. But no one would go so far as to say humans are just bacteria; that’s absurd. We may be more similar to monkeys, but to say we are just monkeys makes about as much sense. And those similarities would be there regardless of common descent.

Now, so far I’ve mostly been talking about what evolution doesn’t mean. So let’s try a more constructive approach. I’ve heard many people muse that our genome contains a large amount of information and that information can’t just come from nothing. Well, one way of thinking about it is that information encodes a history of life on earth; whenever a variant is selected, that is information about the conditions that favored that variant. And if we believe that God’s agency is responsible for that history, then our genome is a record of God’s work since life emerged. A record of God’s work is one way of describing the Bible as well. So, for a Christian, evolution means that an aspect of God’s word resides in the “heart” of every single cell in your body.

Andy has worn many hats in his life. He knows this is a dreadfully clichéd notion, but since it is also literally true he uses it anyway. Among his current metaphorical hats: husband of one wife, father of two teenagers, reader of science fiction and science fact, enthusiast of contemporary symphonic music, and chief science officer. Previous metaphorical hats include: comp bio postdoc, molecular biology grad student, InterVarsity chapter president (that one came with a literal hat), music store clerk, house painter, and mosquito trapper. Among his more unique literal hats: British bobby, captain’s hats (of varying levels of authenticity) of several specific vessels, a deerstalker from 221B Baker St, and a railroad engineer’s cap. His monthly Science in Review is drawn from his weekly Science Corner posts — Wednesdays, 8am (Eastern) on the Emerging Scholars Network Blog. His book Faith across the Multiverse is available from Hendrickson.

Thank you! I’m weary of people viewing evolution as a theory of meaning or a theory of progress. It is a theory of how reproductive success and death shape each successive generation. Nothing more, just reproductive success and death. And that makes it very close to existentialism.

Glad you found it worthwhile, Kevin. You reminded me of another point – I’m not even sure that death is an essential part of evolution. Clearly the actual history of life on Earth includes a lot of death. But you can have differential inheritance of traits without it. Death seems to be more a function of finite resources — a reality no matter how you think we got here — than a specific necessity of evolution.