I am not exactly sure of what prompted me to do it, but I began keep ing a tally of all the pro nounce ments I have done. A pronouncement is that act in which a doctor officially declares a person to be dead. Some deaths are theatric spec tac les involving beep ing mon i tors, electric shocks, and crack ing chest car ti lage. These tend to be chaotic, gritty, and conclusive as in the TV shows, sometimes ending with a dis traught physician intoning, “Time of death. . . .”

However, most pro nounce ments done in the hospital are remark ably simple and imper sonal. Because we attach so much meaning to death and have sequestered it far from the public eye, we are conditioned to believe that its act must be as spectacular and monumental as its significance. But what usu ally hap pens is that the per son will merely expire, often with nothing more than a quiet, gasp ing sigh. It is usually expected but spontaneous, with a somber but quiet family waiting aimlessly for the event to occur. Some times hos pice arrange ments are made for the patient to go home to die, sur rounded by fam ily and friends. Some times a volun teer in the hos pi tal will keep a vigil of sorts, sit ting in a chair while read ing a book or watch ing TV as he or she does the job of those who have no family, waiting to ful fill the simple courtesy of not letting any one die alone. Some times a nurse will make the rounds and dis cover that the patient has passed in the few brief hours in between visits. Regardless, those final moments occur at any hour and in any floor of a large hos pi tal like mine. In every case, when ever the death is dis cov ered, a page is sent to whichever res i dent is on call to stop by and make the offi cial pro nounce ment.

This means that I usu ally know noth ing about either the patient or the fam ily. I have to make an effort to remember the name and the general circumstances leading up to the death long enough to speak with the fam ily and request their per mis sion for an autopsy. The physical exam takes only few minutes, and it requires less than thirty min utes to do all the speaking and doc u mentation before mov ing on to the care of other things.

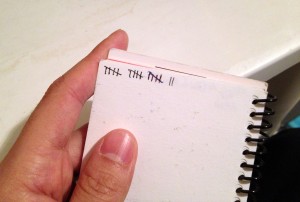

My lit tle tally is noth ing fancy, noth ing more than a series of hatch marks in a small book let of mun dane med ical infor ma tion which I then tuck into my white coat. I hardly remem ber the patients; I can no longer recall any of their names or even what they died from.

But I remem ber the fam i lies. I remem ber the surprising array of reac tions, ranging from jokes and laughter about the whole affair to quiet sniffles into a brother or a sister’s shoul der. I remem ber the words of those left behind, which are often characterized by appre ci a tion and a deep respect for every thing that has been done for this body. I feel unwor thy and deeply unset tled because I had no part in it. . . . in fact, my sole reason for con tact has been that only the remains remain.

If the fam ily is par tic u larly effu sive, I will write a lit tle note of it in the chart: “No pulse, no audi ble heart beat, no spontaneous respirations; no corneal, pupil lary, or gag reflexes. Fam ily expresses deep appre ci a tion for all staff.” And every sin gle time, I am tempted to write, “Kyrie elei son,” an ancient litany that has become a habit to recite when ever I am oth er wise speech less with sor row. But knowing that not all the patient’s fam ily mem bers would appre ci ate such an adden dum, I say it to myself, scratch out a lit tle tick in my book let, and move on.

To “pro nounce” means to state, often with a degree of final ity and cer tainty. But to me, it has also meant to describe and therein impart an element of mean ing. Pro nounce ments are rit uals of anno ta tion and are suf fused with mean ing pre cisely because they are rou tine with out being mun dane. In the heav ily sec u lar ized professions of medicine and academia, we write and state all sorts of things, sometimes searching for the abstract and exotic, while at others struggling to attach meaning to the mundane. I am grateful that some of my clos est times of inti macy with God are moments like these, when the two come together very visibly in the procession of the physical into the ethereal, the ephemeral into the eternal.

Mak ing a note of it is the least that I can do.

But some one may ask, “How are the dead raised? With what kind of body will they come?” How fool ish! What you sow does not come to life unless it dies. When you sow, you do not plant the body that will be, but just a seed, per haps of wheat or of some thing else. But God gives it a body as he has deter mined, and to each kind of seed he gives its own body’

So will it be with the res ur rec tion of the dead. The body that is sown is per ish able, it is raised imper ish able; it is sown in dis honor, it is raised in glory; it is sown in weak ness, it is raised in power; it is sown a nat ural body, it is raised a spir i tual body.

I declare to you, broth ers, that flesh and blood can not inherit the king dom of God, nor does the per ish able inherit the imper ish able. Lis ten, I tell you a mys tery: We will not all sleep, but we will all be changed —in a flash, in the twin kling of an eye, at the last trum pet. For the trum pet will sound, the dead will be raised imper ish able, and we will be changed. For the per ish able must clothe itself with the imper ish able, and the mor tal with immortality.

[This post was edited from its original form, found here.]

David graduated from Princeton University with a degree in Electrical Engineering and received his medical degree from Rutgers – Robert Wood Johnson Medical School with a Masters in Public Health concentrated in health systems and policy. He completed a dual residency in Internal Medicine and Pediatrics at Christiana Care Health System in Delaware. He continues to work in Delaware as a dual Med-Peds hospitalist. Faith-wise, he is decidÂedly Christian, and regarding everything else he will gladly talk your ear off about health policy, the inner city, gadgets, and why Disney’s Frozen is actually a terrible movie.

Leave a Reply