Today is Match Day. Today, thousands of medical students across the USA will be given a sealed envelope containing a description of where they will be going for residency. At noon, in every medical school, they will gather to simultaneously open those envelopes. These students have spent months applying and interviewing for various programs. Many will have spent hundreds of dollars and hours on applications, interview suits, travel expenses, and retail therapy in the pursuit of a place to give them the training necessary to become a board-certified physician. (For my own interviews, I drove up to Boston, flew out to Texas, and trekked from Detroit across half of Michigan, all in the span of a month, and my journey was considered less involved than most.)

Nearly a month ago, these students submitted a final list of their programs in order of preference, and the same programs submitted a similarly ranked list of applicants. Over the past month, both sides have simply been waiting for a single, centralized computer system to work its way through an algorithm and literally assign applicants to programs. It is radically different from applications to undergraduate, graduate, or even most professional schools, where the applicant (in the best scenario) is able to select from a variety of accepting programs and weigh offers and counter-offers.

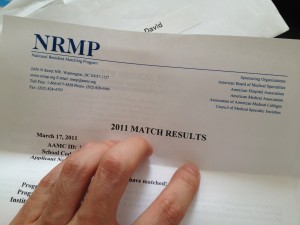

The Match is a singular, contractually binding decision, a mandate of sorts. There is no negotiation, no secondary option. As a student, when you open that envelope you learn your future and are committed to it whether it is your first, fourth, eighth, or last choice. Up until this moment, you have not been able to plan anything following it – housing, spouse requests for a job transfer, loan repayment programs – because you did not know where you would be assigned to. The only thing you knew was that, in three months, you would have to start a new job somewhere, doing something. It is terrifying. It has been two years since my own Match, but I still have pictures of that day pinned to my wall, photographs of a detached composure that belied the intense nervousness and anxiety I felt. There have been few instances in my life where so much of my immediate future was distilled into a single moment of revelation, and I shiver at the thought of future points of such radical change. A pregnancy test, a biopsy result, a phone call, a voice in the waiting room. . . .

I have often been on the side of those delivering the news, occupying that gut-wrenching position where I am about to speak news that will forever change a person’s life: you are pregnant, she has Huntington’s, it is cancer, she is gone, he is dead. These are dra matic moments, and often I find that I have only a few more moments than the patient or fam ily dur ing which to com pose myself. I need those moments because, in vir tu ally every instance, I have far less power to change the out come than they would like to believe.

The third time he said to him, “Simon son of John, do you love me?” Peter was hurt because Jesus asked him the third time, “Do you love me?” He said, “Lord, you know all things; you know that I love you.” Jesus said, “Feed my sheep. Very truly I tell you, when you were younger you dressed yourself and went where you wanted; but when you are old you will stretch out your hands, and someone else will dress you and lead you where you do not want to go.” Jesus said this to indicate the kind of death by which Peter would glorify God. Then he said to him, “Follow me!” – John 21

Match Day is typically a joyful experience. Most of my colleagues, including myself, were assigned to their top three choices. I was ecstatic and ebullient. But I also knew of other students, friends of mine, who quietly slipped into another room to weep in frustration, intensely disappointed that their years of hard labor did not earn them the opportunities they longed for so desperately. Many of them have come to enjoy and love the positions that they are in now, but there are few things in life as bitter as disappointment and the confirmation of fear and insecurity. When we talk about calling, in the vocational sense, in the day-to-day realities of life, we often assume that it is a situation over which we will have some degree of election and control. But in many cases, perhaps the most meaningful ones, it will be a condition in which we will be led where we do not want to go. And yet we are still urged, still called to hear the voice of Jesus who says, “Follow me!” In this Lenten season, let us reflect on the Jesus Christ who was led where He did not want to go, who was obedient to a calling to suffering, humiliation, and death. Let us imitate that obedience, not because of what we can gain and not despite what we fear, but because we love and because He first loved us.

What, then, shall we say in response to these things? If God is for us, who can be against us? He who did not spare his own Son, but gave him up for us all—how will he not also, along with him, graciously give us all things? Who will bring any charge against those whom God has chosen? It is God who justifies. Who then is the one who condemns? No one. Christ Jesus who died—more than that, who was raised to life—is at the right hand of God and is also interceding for us. Who shall separate us from the love of Christ? Shall trouble or hardship or persecution or famine or nakedness or danger or sword? As it is written: “For your sake we face death all day long; we are considered as sheep to be slaughtered.” No, in all these things we are more than conquerors through him who loved us. For I am convinced that neither death nor life, neither angels nor demons, neither the present nor the future, nor any powers, neither height nor depth, nor anything else in all creation, will be able to separate us from the love of God that is in Christ Jesus our Lord. – Romans 8

To all my colleagues matching today, to all those awaiting decisions that may lead them some place new: Godspeed.

David graduated from Princeton University with a degree in Electrical Engineering and received his medical degree from Rutgers – Robert Wood Johnson Medical School with a Masters in Public Health concentrated in health systems and policy. He completed a dual residency in Internal Medicine and Pediatrics at Christiana Care Health System in Delaware. He continues to work in Delaware as a dual Med-Peds hospitalist. Faith-wise, he is decidÂedly Christian, and regarding everything else he will gladly talk your ear off about health policy, the inner city, gadgets, and why Disney’s Frozen is actually a terrible movie.

It’s been amazing to me to watch countless friends go through match day and the weeks/months leading up to it. Each time I’ve been blessed to see God’s hand working in them and through them, no matter if they matched at their first, second, or last choice. It’s great to see God’s plans unfold, particularly when we feel like we have no control of the process or outcome.