Last week, as I began my review of Omri Elisha’s Moral Ambition, I quoted a line that resonated strongly with me:

Here in the Bible Belt, going to church doesn’t make you a Christian any more than going to McDonald’s makes you a hamburger.

In the comments to my post, however, not everyone agreed about the strength of this sound bite. As I’ve reflected on the conversation, I’ve wondered if the difference in understanding is related to a difference in context —specifically, the difference between hearing the line in the Bible Belt and hearing the line as a Christian in academia.

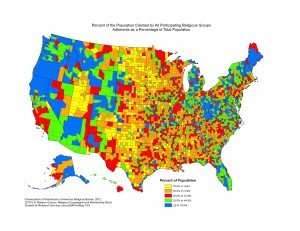

The Bible Belt and the secular academy occupy different extremes with regard to Christianity. This county-by-county map, produced by the 2010 US Religious Census, provides a quick overview of the regional differences in the US.

Blue and green denote low rates of religious adherance, while yellow and orange mark high rates. The regional centers of academic excellence in the United States —the Northeast, Mid-Atlantic, California’s Bay Area —are some of the bluest areas of the country.[1] I’d be very curious to see if the blue counties in the midst of yellow, highly-religious areas correspond to counties that are home to major research universities.

A few significance differences between the role of Christianity in the Bible Belt and in the secular academy have occurred to me, with some accompanying suggestions for different approaches to the context. Let me know what you think, especially if you have experience in both the Bible Belt and the secular academy.

Differences in Context

Dominant Culture vs. Marginal Religion: In the Bible Belt, Christianity is the dominant cultural force. Christianity pervades the whole culture of the Bible Belt, and not simply the religious arena. The debates over the Ten Commandments in public buildings, for example, is about cultural symbolism (in my opinion) just as much as religious convictions about the Ten Commandments. Prayers are a common way to open public meetings, and, as a child, I remember most doctor’s offices offering Bibles and children’s picture Bibles as waiting room reading material.

In the secular academy, meanwhile, Christianity is both marginalized and privatized. It’s not the dominant force of university culture by any means, and those who believe in Christianity are expected to keep it to themselves. Even a small gesture, like keeping a Bible on your desk, as Ken Elzinga as a young professor, can be seen as an act of defiance against the prevailing culture.

Accepted Metanarrative vs. A Hermeneutics of Suspicion: While I’m not sure this is as much the case today as it was in the past, the narrative of Christianity —creation, fall, redemption, consummation —is accepted as the metanarrative for all of life in the Bible Belt.[2] Like Jesus in the Gospel of Matthew, preachers can start their message with “Repent!” and the listeners would not only know what repentance was, but also see themselves in need of repentance.

In the academy, however, every point of the Christian narrative is questioned by one or more academic disciplines. God is not seen as scientifically necessary for creation. The results of the fall can be explained sociologically and psychologically as normal human behavior. Historically, Jesus is one moral teacher among many, and the “redemption” offered by Christianity is yet another form of Western hegemony. Consummation —as in belief in life after death, resurrection, and New Jerusalem —is nonsensical on its face. If you’re trying to life and work within an explicitly Christian narrative in the academy, you have to defend every point.

Shallow Surface vs. Hidden Depth: In my experience with Bible Belt Christianity, there is often a surface religiosity —use of religious language, religious titles, etc. —that disguises a fairly shallow level of faith and spiritual maturity. In a former line of work, I ran a nonprofit ethics watchdog, and, unfortunately, I encountered many con artists who adopted a pastoral title (“Rev. Smith”) or used the word “Christian” in the name of their organization as a shortcut to gain trust.[3]

In the academy, meanwhile, Christianity may be marginalized, but there’s a hidden depth beneath the surface. Most academic disciplines have their roots in the Christian world view, and many secular universities were founded as Christian institutions. I think this is evidenced by the deep, integrative work that Christian academics have been able to do in a variety of disciplines and the good use to which Christians can put the work of non-Christian scholars. Further, far more faculty attend church and take their faith seriously than is generally apparent to an outside observer. In the Bible Belt, there’s pressure to seem more religious than one might actually be, while in the academy the pressure is to downplay one’s religious beliefs.

Does the Different Context Matter?

In the end, we desire the same results, whether in the academy or in the Bible Belt: communities of disciples growing deeper in their relationship with Christ and bearing the fruit of the Spirit. How we get there, though, may require different strategies. Here are a few tentative thoughts about how being a Christian in the academy differs from being a Christian in the Bible Belt.

Simply identifying as a Christian could be a major turning point. One of my campus ministers in college came from California, and she noted that, if someone in the Bible Belt calls himself a Christian, you have to dig deeper to find out what he actually means by that.[4] In other parts of the country, as well as in academia, simply calling yourself a Christian in a public way might be a major step in your spiritual journey. This might include signing a statement of faith in the campus newspaper, as some Christian faculty do, or attending an explicitly Christian gathering, such as an InterVarsity grad or faculty meeting.

Academic Christians might be more comfortable reading theology or Biblical scholarship than reading the Bible itself. It’s always a challenge to get people to read the Bible (and take it seriously), but in the academy, this challenge takes on a different flavor. Where Bible Belt Christianity often privileges “naive” readings of Scripture (“God said it, so I believe it.”), academics of all stripes view naive readings of anything with great suspicion. Since the Bible has its own deep scholarship built up around it, it can be challenging to get academics to read the Bible for themselves. The “Bible” is viewed as an academic discipline unto itself, and reading it without an in-depth understanding of Hebrew, Greek, Ancient Near Eastern culture, hermeneutics, the history of interpretation, etc., is a violation of the academic code of conduct. Theological texts or works of Biblical scholarship might serve as gateways to reading the Bible for academics, as long as the Bible itself is held up as the ultimate goal. (That is, reading theology can become an avoidance strategy to keep oneself from reading the Bible.)

Good questions of interpretation can become obstacles to obedience. If you’ve ever lead an inductive Bible study, with its classic OIA (Observe-Interpret-Apply) model, you know that the interpretation stage can be the most difficult. Often, students want to jump directly from observation to application, without thinking through the interpretation of the passage under consideration. Academics, however, are excellent interpreters, and they are generally experts at identifying the most difficult/interesting questions about a text. The challenge, then, is getting them to keep moving, into application, so that they can become doers of the word rather than merely hearers (James 1:22).

I’m sure I could go further and identify more differences in context and approach, but I want to hear what you think. Do you feel like my analysis of differences between the Bible Belt and academia is accurate? What about my suggestions for different approaches? I look forward to your feedback.

- Not always, however. Note the large blue swath across Appalachia. ↩

- Christian Smith, in Soul Searching, has noted that the understanding of Christian theology is fairly lacking among contemporary American youth, regardless of denomination or religiosity. Even highly religious youth who attend services regularly have a very shallow understanding of their own religion. ↩

- A quick story that feels like something out of a Flannery O’Connor story: While in college, I worked as a server for a while, and one restaurant required me to work a lunch-dinner double shift on Sundays. One Sunday morning, about 11:30, a man was seated at one of my tables by himself. As soon as I walked over, he introduced himself as the “Rev. Dr. Jones” (not his real last name) and ordered a steak and a bourbon. The bartender reminded me that local liquor laws didn’t allow us to serve alcohol before 1pm on Sundays. The “Rev. Dr.” nearly lost his temper over this news, but managed to keep it together when he saw there was nothing I could do. At the end of the meal, he tried to pay with a check, which wasn’t allowed by the restaurant, but my manager approved the exception because he knew the “Rev. Dr.” personally. A couple of weeks later, I learned that the guy’s check had bounced. It was only afterward that I realized how strange it was for a self-identified pastor to be eating by himself on Sunday morning, not to mention the oddity of a guy making such a big deal of his religious title, then nearly losing it when I wouldn’t serve him a bourbon. ↩

- In some cases, it might even mean that he is not a Christian, if he’s using “Christian” as a badge of ethnic or cultural supremacy. ↩

The former Associate Director for the Emerging Scholars Network, Micheal lives in Cincinnati with his wife and three children and works as a web manager for a national storage and organization company. He writes about work, vocation, and finding meaning in what you do at No Small Actors.

I’m a female, California pastor, now serving two small churches in Arkansas. You can imagine all that’s mixed together in that interesting soup. If there’s time later, I’ll write a better comment when I get to a computer, rather than this little phone touchpad. Generally, though, I agree with your post. One quick observation – I learned quickly to not use the word “interpret,” but rather, “understanding,” around “these parts.”

Donna, Thank-you for the teaser! I’m looking forward to your more extended thoughts/commentary on the topic.

This was a helpful analysis. I’ve never lived in the Bible Belt, so I never fully appreciated the cultural dynamics of Christianity in that setting.

I did find it interesting to observe that even though I’ve spent my entire life in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic regions, I’ve essentially always lived in an orange or red county. But I suspect that is at least partly due to the plurality of religious adherents in some of those places, rather than a homogeneous evangelical culture.

It also occurred to me that most of my formative years were spent outside of either of the two cultures you discuss (I realize this was not intended to be an exhaustive list). I grew up in a town that didn’t even have a common language, let alone a common religion. At the same time, many of the Christians I grew up around would not be described as academic. In fact, there were times that I felt just as alien in Christian circles for my academic interests as you describe Christians feeling in the academy.

Thanks, Andy! Some day, I’ll need to do a post about my favorite maps of religion. I think so much can be learned from the geography of religion in the US. Valparaiso has a great collection of maps based on the size of church bodies by county. The map that shows the largest church body in each county is one of the most instructive. With a few exceptions, it’s Baptist in the Southeast, Latter-Day Saint in the Rocky Mountains, Lutheran in the Upper Midwest, and Catholic everywhere else (with a smattering of Methodists throughout the country).

Cool! Maps have always been a powerful tool in public health/epidemiology. I’d be interested to know what other insights can be gleaned from the geography of religion.

[An email response posted by Mike with permission from the author]

I think a lot of academics in the Bible Belt are especially suspicious and often resentful of Christianity as a dominant cultural force, simply because they’re surrounded by it. On the coasts and perhaps the Midwest, academics can essentially live their lives blissfully ignoring Christianity. In the Bible Belt, they couldn’t ignore it if they tried, and this puts an edge on their criticism of Christianity that is sharper than other places I’ve lived. Especially when they see Christians dominating the political stage, as they do here in Texas, they get very edgy and often angry at people of faith. At my institution, I don’t see too much of this. In fact, Christians have a pretty respected place at the table on our campus. But then, we are in the middle of a huge cosmopolitan city, where professors aren’t as fully immersed in Christian culture. My understanding is that it is much more frustrating for faculty members who are “stuck” on our rural Texas campuses.

Your ideas for interacting with faculty seem pretty strong, as long as we’re aware that we in the Bible Belt may have to use kid gloves when presenting our perspectives, because many faculty will assume that we are the Christians they see on TV and in the State House.