)

)As you may or may not have noticed (and if you haven’t, just play along; it’ll make me feel better), I’ve been posting a science link of the week every Wednesday over on the ESN Facebook wall. Facebook seems like a good place for some empirical experimentation; it provides a Wall against which to throw things to see if they stick. By its nature, it’s a bit ephemeral. That’s great if something doesn’t work; before too long it drifts down the screen out of sight, and thus out of mind. But if something was worthwhile, it doesn’t stick around very long either.

So, how about we take the best of those links every month or so and expand them into a blog post. Right now I imagine it as sort of a “director’s cut” version of the Facebook material. I’ll start with the links and comments I posted, and then expand on the discussion that followed. I don’t feel comfortable just cutting and pasting the comments of others wholesale, but I think it’s reasonable to summarize and anonymize that content in the interest of bring the discussion to a wider audience and keeping it moving forward. And since I’ve been trying to frame my links with some questions, I see the blog as a place to offer my (decidedly undefinitive) answers those questions.

Sound good? Here we go!

October 17

Variations on “What if *we’re* living in ‘The Matrix’?” have been around a long time. I’m not sure this particular exploration would be definitive either way, but I do admire their effort to make the simulation hypothesis more concrete and testable. As I understand it, the logic appears to be that a simulated universe will be finite in certain particular ways (due to the limits of whatever platform is running the sim), whereas a real universe would be infinite/unbounded. Do you think that’s a reasonable distinction? What other criteria (measurable or otherwise) might characterize a simulation?

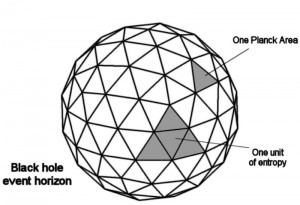

Well, this certainly got some conversation going. The response was basically “no,” it’s not a reasonable hypothesis because we can’t assume the hardware limitations of current computers would apply to a system capable of simulating the entire universe and which exists in some other universe. That’s a fair point. One could respond that the Bekenstein bound, rather than the specifics of current computer implementations, ultimately argues for a simulation which is discrete and bounded in some way, rather than infinite. But one could just as easily argue that the Bekenstein bound does not rule out systems of infinite size or energy which would then be capable of storing infinite information.

More strongly, one could argue that the Bekenstein bound need not apply to the world which is simulating our universe. This is actually a more interesting point, because it reveals another assumption implicit in the hypothesis: that our supposed simulators have constructed a simulation which resembles their real world to a substantial degree. Such a scenario would allow us to extrapolate what we observe about our (simulated) universe and apply it to the real world. Presumably such a scenario occurs naturally to physicists who strive to construct simulations that reflect what we know about our universe as accurately as possible. But there is actually no reason why this has to be the case. The simulators in the real world could just as easily be trying to simulate a universe of a completely different sort, just to see what happens.

And if physicists in the universe-simulation business are more likely to imagine that we are being simulated by like-minded physicists, then perhaps Christians would be more likely (although not exclusively) inclined to assume that we are being simulated by someone unlike ourselves — someone infinite and consequently not fully comprehensible to a finite mind. Christians are used to wrestling with the notion of such a someone, because those attributes could very easily describe the God of the Bible. Consequently, nothing we extrapolate from our scientific observations has to necessarily apply to God; any deviation from what science can observe and what Christians believe about God can be explained away by the infinitude or the otherness of God. This is partly why the existence of God is such an unsatisfying scientific hypothesis. That doesn’t mean belief in God is incompatible with science, but it is a reminder that we should not rely too heavily on the idea that science can prove God. It also helps us empathize with scientists who have difficulty embracing the concept of God.

Having agreed that the research in question makes assumptions that may not hold, I would stop short of dismissing it as worthless science. I offer the following in its defense. First, it formalizes one particular variation of “our world is a simulation” and makes testable predictions. To me, that’s an example of what science does best – it forces us to think about our assumptions in a way that can be clearly articulated and, when possible and appropriate, verified. Second, it is likely the research has benefits beyond answering the (unanswerable?) question of whether we are living inside a simulated world. If nothing else, it should improve our own simulations of the universe. And third, there is value in putting what would otherwise be esoteric research into a context that is of broader interest. It invites conversation from a wider audience, spurs imagination, and, yes, perhaps helps secure grant funding. There is a skill and an art to that sort of contextualization that scientists (myself included on many occasions) can undervalue, assuming that the merits of the work speak for themselves.

Your turn! We’re over a month into the Facebook experiment, and I’d like to hear from you. Which science items captured your attention? Which weren’t worth anyone’s time? Do you want to see more pure science? Less? Would you prefer essays that offer commentary on science? Should I make an effort to cover the history and philosophy of science? Or science and religion? Is my commentary helpful, or should I let the links speak for themselves more? Feel free to provide feedback in the comments. And you can use that space to continue the conversation about this particular story as well.

Andy has worn many hats in his life. He knows this is a dreadfully clichéd notion, but since it is also literally true he uses it anyway. Among his current metaphorical hats: husband of one wife, father of two teenagers, reader of science fiction and science fact, enthusiast of contemporary symphonic music, and chief science officer. Previous metaphorical hats include: comp bio postdoc, molecular biology grad student, InterVarsity chapter president (that one came with a literal hat), music store clerk, house painter, and mosquito trapper. Among his more unique literal hats: British bobby, captain’s hats (of varying levels of authenticity) of several specific vessels, a deerstalker from 221B Baker St, and a railroad engineer’s cap. His monthly Science in Review is drawn from his weekly Science Corner posts — Wednesdays, 8am (Eastern) on the Emerging Scholars Network Blog. His book Faith across the Multiverse is available from Hendrickson.

Leave a Reply