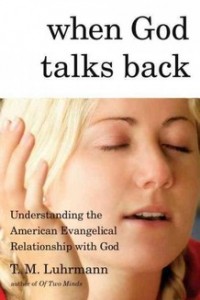

Last week, in my discussion of what evangelicals can learn about themselves from T.M. Luhrmann’s When God Talks Back, I mentioned our approach to suffering. Originally, I wasn’t going to write another post on the book, but I wanted to come back to this important topic. Luhrmann discusses suffering in a chapter titled, “Darkness,” along with the related issue of feeling distant from God. Early in the chapter, Luhrmann describes the Vineyard’s approach in this way:

Churches like the Vineyard handle the problem of suffering [in a different way than traditional theodicy]: they ignore it. Then they turn the pain into a learning opportunity. When it hurts, you are supposed to draw closer to God. In fact, the church even seems to push its congregants to experience prayers that fail [due to their boldness]. (268, emphasis added)

Luhrmann observes that Vineyard churches and other evangelicals face two challenges that aren’t faced by certain other branches of Christianity or Judaism:

- Evangelicals expect an intimate relationship with God. Unlike traditions that few God more distantly, evangelicals want daily closeness with him.

- Evangelicals, particular of the Vineyard variety, expect God to answer big prayers. Luhrmann goes so far as to say that the Vineyard practically sets up its members for disappointment through its encouragement to prayer for healing and success (e.g. being accepted into certain college).

Times of suffering and spiritual dryness are inevitable. How, then, does Luhrmann see evangelicals addressing them?

Community and Spiritual Dryness

First, evangelicals lean on their community. Luhrmann contrasts this with Catholic spirituality, which sees “dryness as an opportunity to experience the life of Christ by suffering in some small way as he did” (283, citing Teresa of Ãvila as an example of this). Luhrmann writes,

In my experience, congregants at the Vineyard did not reach to explain dryness in prayer as a process of identifying with Christ’s suffering…What they said was that in times of dryness and desolation, you needed community, because when an individual’s private experience of God fell short, that individual needed their community to pull them through. (283)

There’s something to this —we do need other people —but there’s also something lacking. Evangelicals have embraced the concept of “life together” as (we think) described by Dietrich Bonhoeffer, while missing the idea that life in community is only one part of life together:

Let him who cannot be alone beware of community. He will only do harm to himself and to the community. Alone you stood before God when he called you; alone you had to answer that call; alone you had to struggle and pray; and alone you will die and give an account to God. (Bonhoeffer, Life Together, “The Day Alone,” emphasis original)

I am not sure if evangelical churches give our members the spiritual resources to be alone before God.

The Availability of God

Evangelicals, however, do see God as their companion in suffering. Luhrmann compares Rabbi Harold Kushner’s When Bad Things Happen to Good People with Philip Yancey’s Disappointment with God:

Kushner concluded that God is good but not all-powerful. That is not Yancey’s God. Yancey settles for a God who is logically incoherent but emotionally available, and the point Yancey makes is that the awesome, mighty creator of the universe is desperate that we should like him and hurt when we turn away, regardless of the devastation going on in our lives. (288, emphasis added)

I have not read Disappointment with God, so I can’t say whether Luhrmann’s description is accurate. Again, though, I notice that the sufferings of Christ don’t factor into this evangelical discussion of suffering. Interestingly, Lurhmann brings up a study that found that a “secure attachment to God…protects college women against eating disorders and college men against excessive drinking and drugs” (290). Perhaps the emotional availability to God is more important than logical consistency or theological sophistication.

Grief and God

Luhrmann describes the heartbreaking story of a young evangelical couple, whom she calls Peter and Amanda. Amanda was pregnant with their second child when, in the eighth month, they discovered during a routine checkup that the baby had died in the womb. While they had been typical “joyful” evangelicals, this tragic loss had changed their relationship with God:

Now, when they read the Bible, they saw pain and mystery. Amanda said that she had come to realize that when Job’s wife told him to curse God and die, the wife wasn’t thinking about logic. She was hurt….For all the church’s emphasis on God’s there-ness, God’s presence as a friend, they still felt a terrible rupture. They felt numb immediately after the child’s death, and when I sat down with them two years after the funeral, they still felt numb. Yet they came to church regularly. They believed in God, and they believed that their relationship with God would, in time, recover. (294, emphasis added)

This numbness is a normal reaction after a loss like theirs. Luhrmann summarizes evangelicals’ approach to God in the midst of suffering as primarily therapeutic, not explanatory:

What they want from faith is to feel better then they did without faith. They want a sense of purpose; they want to know that what they do is not meaningless; they want trust and love and resilience when things go badly…when you look at what people actually do in the religion, you see that they want a God who helps them to cope when the going gets tough. (295, emphasis added)

Suffering and the Bible

Is there anything wrong with that, with wanting comfort and purpose? No, not at all. Still, I think something is missing in evangelicals’ response to suffering: the Bible. This may seem strange, considering that evangelicals are usually regarded as the most Bible-centric of all Christian traditions (though I don’t think we actually are). However, in this chapter, when Lurhmann references passages of Scripture that evangelicals use in response to suffering, it’s almost always either Job or a story from Jesus’ ministry.

What’s missing?

- The Psalms, particularly the Lament Psalms, which make up one-third of the Psalter

- Hebrew prophets like Jeremiah or Isaiah, who wrestled with the enormous discrepancies between God’s promises and their reality

- Anything about the cross or resurrection

I have found that, when I feel distant from God and struggle to pray, the Psalms can become my prayers. I have also turned to resources like the Book of Common Prayer, both the collects and the BCP’s funeral service —the “Order for the Burial of the Dead” —which brings together some of the most profoundly comforting verses in all of Scripture:

I am the resurrection and the life, saith the Lord: he that believeth in me, though he were dead, yet shall he live: and whosoever liveth and believeth in me shall never die. (John 11:25-26)

I know that my Redeemer liveth, and that he shall stand at the latter day upon the earth. (Job 19:25)

I am persuaded that neither death, nor life, not angels, nor principalities, nor powers, nor things present, nor things to come, nor height, nor depth, nor any other created thing, shall be able to separate us from the love of God, which is in Christ Jesus our Lord. (Romans 8:38-39)

I’m not sure why evangelicals don’t turn to the cross and resurrection. Crucicentrism —focus on the cross —is one of the “Bebbington quadrilateral,” the four defining characteristics of evangelicals. Perhaps it’s because Christ’s sufferings seem “too Catholic” (rare is the evangelical church that has a crucifix rather than an empty cross). Perhaps because we have blinders on, seeing the cross clearly in atonement but overlooking its role in daily life. It might even be socioeconomic —as North Americans, we see suffering as an exception rather than the rule. Regardless, this is an area in which we can learn a great deal from our fellow Christians, both in other traditions and around the world.

The former Associate Director for the Emerging Scholars Network, Micheal lives in Cincinnati with his wife and three children and works as a web manager for a national storage and organization company. He writes about work, vocation, and finding meaning in what you do at No Small Actors.

Michael thanks for this article/review! I’ll chime in that when I was at an Evangelical seminary, in preaching classes, in which form was primarily graded over content, I picked a couple of unhappy stories from the OT. Essentially I was told everything was great, but that I should have given it a happy ending (content) because I should introduce (something about God (such as Grace)) which was not contained in the story. The example I have in mind was preaching about Achan’s sin (Joshua 7). The professor said I should have said (“now if Achan had repented … God would have had mercy”), which I think is sick because I don’t know what God would have done. I also knew this was a special case of sin–taking the ‘devoted things’. Anyway, even if Achan had repented, it wasn’t cool with the 36 Hebrews soldiers who had to die because of this; I have always thought and still do that we should at times be unsettled by what is there in Scripture.

For many years I personally have found what I view a false happiness most evangelical sub-cultures very off-putting. I see this in even in the Church architecture and in the religious symbols (lacking or present), so one-up on your point about the cross/crucifix.

“Unsettled” is very apt. One of the challenges for the Church when it is culturally ascendant is to continue cultivating the subversive aspects of the Gospel. The Scriptures give us a portrait of a world that is broken; we should be uncomfortable with that brokenness. This is also one of the purposes of suffering — like the barrenness and severity of the wilderness, it reminds us that we are not meant to settle here and keeps us moving towards our true home.

Thanks, Jon. With Andy, I say “yes” to the idea of being unsettled by Scripture. I’ve long been attracted to passages of Scripture that don’t lend themselves to easy understanding or interpretation. We should also be more comfortable with the idea that our preaching/teaching is a process that takes time. I’ve mostly attended churches whose preaching was heavily influenced by the revival circuit. The underlying assumption is that this is the preacher’s one chance to reach someone with the gospel. There’s a need for that kind of preaching sometimes, but, in reality, most churches are made up of a community in the same place over a period of time.