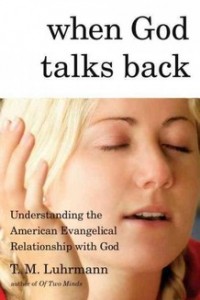

For the past several weeks, I’ve been reading T.M. Luhrmann’s When God Talks Back: Understanding the American Evangelical Relationship with God. The book addresses a simple, but profound, question from the perspective of a nonbeliever: how can seemingly rational, otherwise normal people claim to discern God’s will, to hear God’s voice, and, sometimes, to even see or feel spiritual beings? Luhrmann asks this with genuine curiosity, both personal and professional. A psychological anthropologist who has written previous books about modern witches, Zoroastrian Parsis, and American psychiatry, Luhrmann spent four years attending Vineyard churches and participating in Bible studies, prayer groups, and church seminars in preparation for the book. In addition to her own observations, Luhrmann ran the Spiritual Disciplines Project, an experiment at Stanford to explore how spiritual practices like prayer and Bible study affected individuals’ perception of spiritual things. When God Talks Back is the result of these observations, experiments, and Luhrmann’s synthesis of the literature on Christianity and other religions.

Much of the book focuses on sensory perceptions of “unnatural” phenomena —voices, visions, physical sensations of people who are not there. Augustine’s conversion story in his Confessions is a great example of this. While alone under a fig tree wrestling with whether to follow Christ, he hears a child’s voice singing “Tolle, lege, tolle, lege —”take and read“ in Latin —but he knows somehow that isn’t just a child’s voice. He picks up a Bible, reads the first verses that he finds (Rom. 13:13-15), and ”all the shadows of doubt were dispelled” (Confessions, Book VIII).

Luhrmann chooses to examine Vineyard churches because she notices that experiences like these, as well as the more common process of discerning God’s will through prayer, study, and community, are much more common and accepted as authentic spiritual encounters in evangelical, charismatic, and Pentecotal churches than in the mainline Protestant church in which she was raised. In her research, Luhrmann finds that sensory experiences like these are much more common than some might think. Between 10% and 15% of the population volunteer when asked that they have heard voices or seen people who they knew “weren’t there.” The number rises to nearly 50% when the question is accompanied by a prompting example.

Luhrmann is careful to note that these experiences are not signs of mental illness —she devotes an entire chapter to the question “But are they crazy?” —but a rather normal part of human life quite distinct from schizophrenia or other illnesses that cause people to have hallucinations. She notes that people who have had such experiences are accuately aware that hearing a voice or seeing an apparition might be viewed as a sign of mental illness. Whereas schizophrenic visions are typically constant, disturbing, and compelling (that is, the person feels they must obey the voice and have to fight against it if they don’t want to), the sensory experiences studied by Luhrmann tend to be:

- occasional: most people report having only one or two of these “sensory override” experiences, though Luhrmann believes that people have many more and simply forget them or explain them away)

- not disturbing: a woman reports seeing her dead father walk into the room and disappear, but it’s not emotionally disturbing in any way)

- not “compelling”: that is, even if it’s experienced as the “voice of God,” the person still feels they have complete control over their choices and reaction)

Further, regular prayer practices, which increase the likelihood of having these sensory override experiences, are often associated with improved mental and physical health.

Luhrmann herself shares an account of her own experience —a vision of six druids standing outside her apartment window while she was in England studing modern practitioners of magic. Throughout the book, she is careful to separate the study of these sensory perceptions from the question of whether or not they are “real.” In other words, Luhrmann practices good methodological naturalism.

I was planning a straightforward review of the book, but several others have done a much better job than I could have. In particular, Mark Noll reviewed Luhrmann’s book for The New Republic, and I highly recommend his review for anyone seeking an overview and assessment of Luhrmann’s project. Go read it.

Rather than a review, I’m going to share a few lessons that I’m taking away from reading When God Talks Back. In my next post, I’ll discuss a few ideas for fruitful engagement between evangelicals and non-evangelicals. In the post after that, I’ll share thoughts for how When God Talks Back can inform our self-understanding as evangelicals. In the meantime:

- Have you read When God Talks Back?

- What do you think of Luhrmann’s research and writing?

- What differences do you see in the ways that evangelicals and mainline Protestants experience and talk about God?

The former Associate Director for the Emerging Scholars Network, Micheal lives in Cincinnati with his wife and three children and works as a web manager for a national storage and organization company. He writes about work, vocation, and finding meaning in what you do at No Small Actors.

A very relevant topic; I’ll have to add this book to the reading queue. I have encountered many people who are certain that claiming to talk to and hear from an invisible deity is a sign of mental illness.

Does the book discuss the cognitive science and neuroscience dimensions of this topic? The mind is a fascinating thing; so much goes on between the raw sensory input we take in and the final perception that our mind deals with. I wonder just how many of the experiences described here sneak in between those two levels.

Which is not to say that if we were able to some mechanism or process that is associated with such experiences, that it would eliminate any possibility of divine or spiritual agency.

Good question, Andy, about the neuroscience. I don’t recall that aspect coming up, though I may be forgetting something. Luhrmann does note that people who hear from God are more likely to have stronger imaginations (according to psychological scales that measure imaginative ability). In Luhrmann’s spiritual disciplines experience, subjects who practiced kataphatic prayer (in which participants visualized scripture, similar to Ignatian exercises) increased their overall imaginative ability. Imaginative ability and the tendency to hear from God were also correlated with high scores on a scale that was originally designed to measure hypnotic susceptibility, though Luhrmann notes that the scale is now regarded as more complex than that.

Regarding the mechanism or process, you’re absolutely right, and I think Luhrmann touches on that idea – that, just because there is a physical or neurological process doesn’t “explain away” the phenomenon. On an MRI, our brain lights up in certain ways when we listen to music or look at a tree, but that doesn’t “explain” either music or trees.

It’s remarkable how, the further we progress in science, the deeper we go into philosophy. The question of whether our perceptions map to reality was a central issue in my “Modern Philosophy” course I took as an undergrad – “modern” meaning Descartes, Leibniz, Berkeley, Kant, et al., who all lived and died long before neuroscience existed.

Thanks for the follow-up, Michael. You’re right to note that oftentimes when science arrives on new shores, it discovers territory that has been inhabited by philosophers for decades or centuries.

And things do get especially tricky when trying to study the brain and the mind, with so many different overlapping disciplines and levels of inquiry (not to mention the fun of puzzling out how something can study itself). I wasn’t even certain that neuroscience was the right term for what I was describing. Personally, I think if you’re not even sure what to call an area of study, it probably means it’s a fruitful one with lots of unanswered questions to explore.