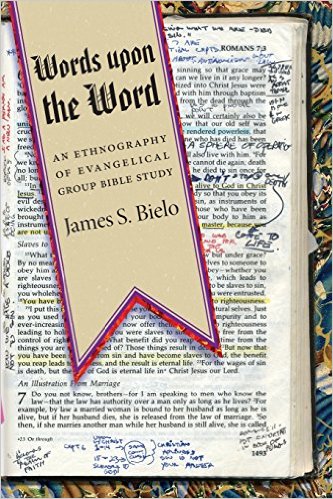

I’m currently reading Words Upon the Word by James S. Bielo, an ethnography of evangelical Bible study groups in Lansing, Michigan. Last week, I looked at Bielo’s introduction and the question of Bible study as a cultural institution. This week, I continue with Bielo’s first chapter, in which he describes his methods for selecting and observing the Bible study groups. In the progress of his research, two issues with significances to the Emerging Scholars Network arose. The first: the varieties of meaning behind the word “Christian.”

“Are you a Christian?”

If you have visited many evangelical churches, you’ve likely heard the question “Are you a Christian?” or some close variation. Depending on the context, it can be a tricky question to answer well. As Bielo writes, it’s especially tricky when you are an ethnographer visiting a Bible study in order to observe it for a research project.

How have anthropologists responded to this question? Frankly, the most common approach is silence, an avoidance of how this matter of identify impacted the research. It is a sort of don’t ask-don’t tell policy —one that is always conspicuous in its absence. For those that do address the issue, the dominant narrative is hardly surprising. It is somewhat of a truism, at least in the United States, that religious faith can be hard to come by in the academy —a fact appearing in exaggerated form among anthropologists….In responding to the question [in a Carnegie Foundation survey] “What is your religion?” anthropologists refused to claim any affiliation at a rate of 65 percent, ten points above the next discipline (philosophy) and more than twice the mean for all others. (Bielo, 30-31, emphasis added)

Bielo, however, doesn’t favor this approach. Instead, he prefers an approach influenced by Brian Howell’s suggestion that a Christian studying Christians is similar to “the feminist studying women, the leftist studying labor unions or the Muslim studying mosques” (32, quoting Howell’s “The Repugnant Cultural Other Speaks Back: Christian Identity as an Ethnographic ‘Standpoint.'”)

The question “Are you a Christian?,” though, means different things in different churches. InterVarsity staff or anyone who navigates between different varieties of Christianity know this, and I was impressed with Bielo’s discussion of “Six Iterations of ‘Are You a Christian?'” in this chapter. Of the six churches in Bielo’s study, three are United Methodist, and the remaining three are Lutheran-Missouri Synod (LCMS), Restoration Movement (Christian Church/Churches of Christ), and Vineyard.

At one UMC church, which had gone through several local versions of the theological debates in the UMC, Bielo notes that answering “yes” to “Are you a Christian?” was “always the end of the discussion” (34), because they expected theological diversity at the church (and, I wonder, perhaps didn’t want to open old wounds with every visitor). At the LCMS, answering “yes, I am Christian” wasn’t enough for Bielo —he then had to address whether or not he was Lutheran. At the Restoration church, Bielo came to understand that “Christian” was used as a synonym for “born again” —they wanted to know whether he had experienced a personal conversion experience, but, unlike the LCMS, weren’t overly concerned with his denominational identity. Even though Bielo doesn’t consider himself “born again,” he risked answering “yes” because he saw this question in the Restoration church as a “ritual of inquiry,” as primarily a means of establishing shared identity. Meanwhile, at an UMC congregation that had been strongly influenced by the “Emerging Church” (no relation to ESN), simple answers to the question “Are you a Christian?” were met with skepticism. The question

is an invitation to share the doubts, questions, challenges, and confusions you struggle with….The assumption is that articulating theological differences and doubts is an edifying experience, one that draws a community closer together and defines their life of faith as an ongoing dialogue. (35)

I think I’ve encountered every one of those variations! In addition, perhaps as a result of visiting so many Bible studies, Bielo discovered that the question “Are you young in your faith?” came up regularly, and his answer also affected his relationships with those in the Bible studies.

It wasn’t only Bielo’s identity as a Christian that came up, though, when introducing himself to these Bible studies. He soon discovered a third question that he had to answer: “Are you an academic?”

“Are You an Academic?”

Here, Bielo goes in a surprisingly pleasant direction. “On the one hand,” he writes,

there is a dominant discourse among conservative Evangelicals that the academy is a territory where Christians must tread lightly. It is the breeding ground of “liberalism,” “humanism,” “secularism,” and a variety of other unsightly “isms” that are antagonistic to Christians and Christianity. (40)

Nothing new there. But he goes on, and I’ll quote him here at length:

Yet, on the other hand, conservative Evangelicals are not anti-intellectual, nor do they renounce post-secondary education. They are voracious readers who conceptualize their Christian heritage as one of brilliant thinkers and writers. They point to St. Augustine of Hippo, Martin Luther, John Calvin, John Wesley, G.K. Chesterton, and C.S. Lewis as learned men, exemplars of intelligent Christianity, and individuals who are genealogically important to the literary and intellectual culture of contemporary America. They are well aware that the field of hermeneutics (though many do not call it by name) exists because of scriptural study. And they point to the Christian origins of many universities, including several Ivy League institutions. Many of the individuals I encountered during my fieldwork had earned baccalaureate and advanced degrees from secular universities. Many of these same individuals send their children to public universities and emphasize the necessity of higher education. (40, emphasis added)

Moreover, because his fieldwork took place in Lansing, Michigan, home of Michigan State University, he finds that many members of the Bible studies take pride in their local university and support it in myriad ways. Twenty years after Mark Noll’s Scandal of the Evangelical Mind, it was wonderful to see a non-evangelical writing in this way about evangelicals.

In short, conservative Evangelicals have a conflicted relationship with “the academy.” It is both friend and foe and is all the while acting as a “spiritual battleground,” a place where the public status of Christianity is at stake. I was reminded of this social fact time and again during my fieldwork. On occasions that were too numerous to count, I was asked how openly Christian students were treated at Michigan State, if I had any colleagues who were not anti-Christian atheists or “secular humanists,” if I was a “liberal,” if I let my personal politics enter the classroom, if I taught evolution, and so on. (41, emphasis added)

Sound familiar? It certainly does to me.

Overall, Bielo’s treatment of these two issues of identity —being a Christian and being an academic —mapped onto my own experiences in evangelical churches. Too often, I read accounts of visits to evangelical churches that take the “flavor” of evangelicalism experienced as normative for all evangelicals everywhere, indicating that the author really doesn’t know evangelicalism very well. Just as the spiritual condition of the academy is a truism among conservative Christians, so too is the intellectual condition of evangelical churches in secular literature, without stopping to notice the complex relationship between evangelicals and the academy. The stereotype of evangelicals is that we are rural and uneducated, but this stereotype was false 25 years ago, if it was ever true.

What have been your experiences? What varieties of “Are you a Christian?” have you encountered? How do you answer questions about being an academic in evangelical churches?

The former Associate Director for the Emerging Scholars Network, Micheal lives in Cincinnati with his wife and three children and works as a web manager for a national storage and organization company. He writes about work, vocation, and finding meaning in what you do at No Small Actors.

Leave a Reply