Do you find it hard or easy to discuss the big questions about God? Explain.

Kent writes that his search is for “honest faith.” Do you ever encounter in yourself or in others something that seems like less-than-honest faith? How would you define “honest faith”?

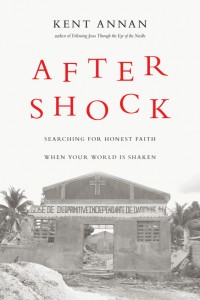

— From the Reading Group Guide for Kent Annan’s After Shock: Searching for Honest Faith When Your World Is Shaken (InterVarsity Press. 131 – 133).

I wasn’t intending to read After Shock (Kent Annan. IVP. 2011) through Lent, but the intensity of Kent’s wrestling with faith-life-work made it difficult for me to read long stretches of his short book (137 pages). As such I didn’t finish After Shock until recently.

But for that I am grateful. After Shock offers a powerful Lenten reflection, even including thoughts on Ash Wednesday, Footwashing, Communion (Last Supper), Peter’s denial, the crucifix vs. the cross, Easter.*

Some days I wondered if I should pick up Kent’s Psalm. In writing this post, I had a number of quotes which I desired to draw from

- how Kent tells the story of Enel surviving the collapse of his University classroom building

- interactions with the jubilant Haitian followers of Christ who survived while standing in the midst of destruction

- how he describes relief work by faith, hope

- his conclusion.

But the below section contrasting The Benefit-of-the-Doubt God and The Guilty-till-Proven-Innocent God struck me as most applicable to our campus setting:

Many people, when God’s goodness comes into question, think of God in one of two ways:

1. The Benefit-of-the-Doubt God

This is the God presumed by pop culture and promised, in its worst form, by the prosperity gospel. Professed by proof-texting and a secret belief in positive-only karma, this God wants wealth and goodness and happy endings. Essentially, God is the director of life’s romantic comedy—inserting plot conflict to keep it interesting and to give characters opportunity for personal growth, but pulling strings so the ending is ultimately redemptive in this life.

When the plot goes really wrong, then it’s our fault, not God’s; we don’t believe enough or aren’t good enough. If we find we can’t blame ourselves, we console ourselves that it’s only a movie; the divine reality is yet to come. Hope and faith come at the cost of truth.

There are of course other, better versions of this. Actually, most of the devout Haitians I know think this way, even after the earthquake. The friends I talked with about these questions were still in worship, still devout, seeing the earthquake as a problem of nature and not a problem of God.

2. The Guilty-till-Proven-Innocent God

This approach says God is on trial for the sufferings of this world—and the verdict is not promising. Goodness and beauty do not balance out the horrors. Or at the very least it’s a draw. Those who view God this way consider benefit-of-the-doubt believers naive. What kind of good Creator could possibly survive when 230,001 people don’t survive under the created order (and human-created conditions) that just crashed on them?

One of novelist Dostoyevsky’s characters in The Brothers Karamazov doesn’t shy away from putting God on trial. He famously details the suffering of a boy and girl and concludes that he will respectfully return his ticket (to life) back to God—because even all the goodness of the world cannot be justified by the horrific suffering of one innocent child.

These two options aren’t a rubric for understanding how every-one approaches the problem of evil-good. But when I vacillate, it’s often between these two stances, which are both related to uncertainty. We have to (by faith, one way or another) try to make sense of so much good and so much evil—and what this says about God. All the cloud and dust of witnesses, the beauty and the cruelty of our world, the screaming and the singing, the glory and the horror of human experience must be called forth to testify.

While I was watching a basketball game the other night, an ad came on during a timeout. A montage of women’s faces, one after the other, concluded with the statement, “A woman is sexually assaulted every two-and-a-half minutes.” Then back to the game.

How do you go back to the game? Confronted with evil—an evil that will be repeated within two-and-a-half minutes, and then two-and-a-half minutes after that, multiple times before the next time-out. With any number of other evil acts and senseless suffering filling the seconds between assaults. Every moment, if we have eyes to see, presents another tangible reason for a crisis of faith.

At times, pain shapes us in good ways. We can’t deny that. C. S. Lewis called it God’s megaphone for getting our attention for our own good. But it can also crucify. And uncertainty in the face of it can leave us feeling paralyzed or stranded. It can make the leap of faith seem like a leap off the balcony of reality. — Kent Annan. After Shock: Searching for Honest Faith When Your World Is Shaken. InterVarsity Press. 2011. 46 -47.

As for the above questions, God’s in-breaking and continued presence/care has led me to be one who constantly lives in and discusses big questions about God. Even with all the campus and blog conversation, I try to stimulate more 😉

But family in particular has taught me that listening and being present is a significant part of the gritty-ness of “honest faith,” both in relationship with God and other/neighbor. What is honest faith? Some initial thoughts: Living in the reality of loving/trusting God with head, heart & hands as given direction by the Word, Spirit, and Body of Christ (of which one is a part). To confidently see and prayerfully walk with the eyes of God. Texts such as Matthew 22:35-40, Mark 11:24, Romans 10:17, 1 Corinthians 15:1-4, 2 Corinthians 5:7, Ephesians 2:8-9, Hebrews 11-12 (not just 11:1), point me in this direction and sustain me in this call. To God be the glory!

How do you respond when

- asked about God on campus?

- facing questions about “honest faith” in your own life?

*Closer to Easter, I’ll return to Kent’s reflections upon John Updike’s Seven Stanzas at Easter.

Tom enjoys daily conversations regarding living out the Biblical Story with his wife Theresa and their four girls, around the block, at Elizabethtown Brethren in Christ Church (where he teaches adult electives and co-leads a small group), among healthcare professionals as the Northeast Regional Director for the Christian Medical & Dental Associations (CMDA), and in higher ed as a volunteer with the Emerging Scholars Network (ESN). For a number of years, the Christian Medical Society / CMDA at Penn State College of Medicine was the hub of his ministry with CMDA. Note: Tom served with InterVarsity Christian Fellowship / USA for 20+ years, including 6+ years as the Associate Director of ESN. He has written for the ESN blog from its launch in August 2008. He has studied Biology (B.S.), Higher Education (M.A.), Spiritual Direction (Certificate), Spiritual Formation (M.A.R.), Ministry to Emerging Generations (D.Min.). To God be the glory!

I was surprised that these were the only two options presented. Given these two, I’d say I fall into the “Benefit-of-the-doubt God” model. Evil (human and angelic) and the curse on nature are very real – not just a movie – but God allows these in order to display His love and logic. No evil or curse? No free will. No free will? No love. I don’t view God as the Creator of evil so much as the allower of evil and the Creator of a world in which evil can take place. Ultimately, He will work all for good.

Today I was contemplating the analogy that a tomato can grow from manure. The tomato is good food, the manure isn’t. Similarly, I see how God grows good out of evil. The good is the blessing, the evil isn’t. A tomato is not manure in disguise, and evil is not a blessing in disguise.

Mankind’s decisions are to blame for the curse on nature, while mankind and angelic decisions are to blame for evil. God determines the nature of man; the nature of man determines our choices; our choices determine our situation. We wouldn’t live in a fallen world were it not for our decision to rebel, and wouldn’t have rebelled had God made us with no capacity for rebellion. We are responsible for the curse, yet God has made Himself responsible for redemption. If the curse seems unmerited, then the redemption is also unmerited, so God is ultimately both just and merciful. He took the blame for what His creation did, and fixes it.