As you may remember from No football. Campus tradition rooted in peace-making, I’ve been working on a Theology of the Church paper exploring how Elizabethtown College, founded to keep youth within the Church of the Brethren, fared in teaching denominational doctrine and way of life. In the earlier post, I shared how no football embodied the Church of the Brethren way of life. How well did peacemaking extend beyond no football, particularly in the face of 20th century military engagements? How well has your campus worked out the purposes of its founders. How about ideals which were/are countercultural (possibly even culturemaking)? Any stories to share?

Introduction

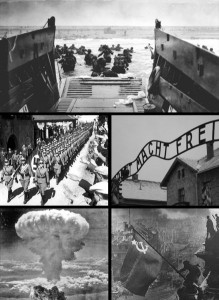

World War II Indicates Future Direction

The pop quiz which opens Elizabethtown College: The First Hundred Years includes the question, “’Because of its pacifist heritage, very few Elizabethtown students joined the armed services during World War Two.’ (False. See page 43)” (Downing, 1). On page 43 one finds a tribute to the 135 Alumni and Former Students in the Service which appeared in the 1944 Etonian. Two receive stars indicating that they had been killed in action as of January 1, 1944. The opposing page features a tribute consisting of a flag, the pictures of the three servicemen, and the text “We salute these OUR BOYS.”

Earlier in Elizabethtown College: The First Hundred Years, the article Pacifists and Patriots emphasizes the student’s split opinion as World War II approached, with many having the desire to choose for themselves (Downing, 37). Williamson draws attention to the results of a poll which ran on the front page of the October 19, 1939, issue of The Etownian:

Thirty percent of the students indicated that they would be willing to support the United States in a war against Germany, should England and France appear to be losing. Possibly the same 30 percent said that they would be willing to support their country in any foreign war it declared.

Fifty-six percent believed that the teachings of Christ did not condone war.

Twenty-nine percent believed that war was inevitable (Williamson, 149).

With regard to the embracing of World War II, Williamson writes:

“The change in the attitude of the College to the war was abrupt. There were no more calls from students for neutrality. Instead they wrote articles like “Good Marksmanship,” in which freshman Philip Greenblatt praises the shooting abilities of American soldiers. ‘Our fore-fathers who were utterly unfamiliar with all military movements, but who were sure death as shots were able to overwhelm much superior forces of the best-drilled soldiers of Europe, and the truth of those facts have not changed.’

Greenblatt’s paean to riflemen seems almost Gandhian in comparison to ‘The Mission of United States” by senior Aaron Edris:

Is there one so cowardly among us, as to allow this noble nation to die in cold blood? Fellow-citizens, arise to service. The man who does not serve his country is not worthy of a country.

If, to-day we will not clasp the sword to preserve democracy, to-morrow we will take up arms to defend aristocracy. ’ Never let us for one moment forget the high and holy mission with which we entered this war, no matter what it costs. ’ Give me democracy or give me death. …

It was most definitely not the position of the Brethren Church. Several months before, on January 9, the church’s General Conference, meeting in Goshen City, Indiana, declared that “’war or any participation in war is wrong and utterly incompatible with the spirit, example, and teachings of Jesus Christ.” This “Goshen Statement” further urged Brethren not to enlist in the service, wear a military uniform, drill, learn any of the arts of war, or do anything that would contribute to war. ’(81)

But elsewhere in Williamson, one reads:

W]ith the CPS [Civilian Public Service] program well established, only 10 percent of Brethren youth chose this option, while another 10 percent selected noncombatant military service. Approximately 80 percent chose combatant military duty when the time came. Most of the Brethren churches were supportive of their men in uniform from the start of the war, a striking contrast to earlier wars in which the combatants would have been either severely disciplined or ejected from the church. ’ In most Brethren congregations it was already acceptable to be a soldier (156).

In April 1942, the first ever combined gathering of faculty, the Alumni Council, and trustees occurred with the focus on how to address the financial losses due to the downturn in enrollment resulting from World War II. Although Elizabethtown College refused to allow military training on campus, recruitment officers received permission to make campus visits (1942), letters from servicemen were published in The Etownian (1942), and lists of Men in Service began running in every issue of The Etownian (1943).

Downing writes:

The 1940’s represented a time of turning toward the future for Etown. The strict control of the church was declining, and, at war’s end, classes grew larger each year. As the first half-century of Elizabethtown College closed, the school pushed forcefully into the next, gradually relaxing its social codes and preparing for the upcoming era of McCarthyism and rock-and-roll. (38)

This decade also brought to Elizabethtown the turmoil of World War. Air raid instructions appeared in The Etownian. The College watched the first boys leave for service and wished well the men, and women, that followed. As the total number of male students fell to single digits, heads bowed for the students who would not be returning home at war’s end.

G.I. Bill as the Savior of Elizabethtown College

According to Williamson, “The G.I. Bill proved a blessing to Elizabethtown College, and could not have come along at a more opportune time” with five returning veterans enrolling in the fall of 1945 and thirty more at the beginning of the spring term (161). After a three-year building and endowment campaign “the College [was] on its best financial footing ever” (Williamson, 161). According to all reports, the influx of older, more mature students with a concern for others changed the complexion of the campus. In addition to their international experience, the returning servicemen had a point of view which had little time for “being told what to do activities” such as initiation placards and chapel sermons decrying the horrors of war. As army barracks were built on campus (Downing, 46) and the school received Middle States Association accreditation (Williamson, 165), the Church of the Brethren bubble burst.

Elizabethtown College no longer preserved their denomination’s youth or the denominational ideals upon which they were founded. These concerns had been expressed before the development of institutions of higher education related to the German Baptist Brethren/Church of the Brethren and afterward when the schools received significant attention in order to address athletics, dress, higher criticism, and the practical Christianity inspired by the Social Gospel movement (Hanle, 236-237). Looking back, in the 1940’s the college bulletin transitions to articulating the campus ideals as “Christian,” loosing the distinctiveness of its Church of the Brethren roots. Pacifism/peacemaking is not included in the listing of ideals.

Campus Reaction to the Korean and the Vietnam Wars

Due to the strong anti-communism on campus, the Korean War received no on-campus critique (Downing, 51; Williamson, 187). In contrast the Vietnam War caused significant controversy. Peace seminars and marches stood in contrast to an overwhelming conservative faculty and student support of the government (Williamson, 224). The differing perspectives came to a head with some students hanging in effigy Professor J. Kenneth Kreider, who openly opposed United States military action in Vietnam (Downing 62-63). There was no official response to the incident and it was not reported by the campus newspaper, but lots of conversation ensued. In 1970, the Church of the Brethren stated that military recruitment on the six Brethren college campuses was inconsistent with the policy of the Church. Later in the year, Elizabethtown College voted to

cooperate with the policy of the Church of the Brethren relating to alternative service ’ representatives of the various military service, upon their request, shall be permitted to present professional information as sought by students. Enlistment shall not be permitted on the campus.”

The Board of Trustees on January 16, 1971, essentially affirmed the position adopted in December by the Community Congress:

“Elizabethtown College shall welcome qualified persons to dialogue with members of the campus community on all issues of war and peace. Representatives of the various military services, upon their request, shall be permitted to present professional information as sought by students. Enlistment shall not be permitted on campus.

The College shall continue to encourage programs relating to alternative service, recruitment for the ministry, volunteer service and similar programs.”

The College for years had permitted recruiters to visit the campus, but beginning in 1971 military personnel were limited to the explanation of their programs and to answering questions in the Office of Placement Services (Schlosser, 324-325).

Next post in series … Rebirth of Peacemaking in a Much Different Context

References

Downing, David C. Managing Editor. Elizabethtown College: The First Hundred Years. Manheim, PA: Stiegel Printing Inc., 1999.

Elizabethtown College. Catalog. Elizabethtown, PA: Elizabethtown College. 1900 – .

Elizabethtown College. Student Handbook (The Rudder). Elizabethtown, PA: Elizabethtown College. 1926 – .

Falkenstein, George N. The Organization and the Early History of Elizabethtown College. Publication Info [s.l. : s.n.]. 193-.

Hanle, Robert V. A History of Higher Education Among the German Baptist Brethren: 1708-1908. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Pennsylvania, 1974. Note: A special thank-you to Matthew Shindell for his recommendation of this insightful piece.

Schlosser, Ralph W. History of Elizabethtown College: 1899-1970. Lebanon, PA: Sowers Printing Company, 1971.

Williamson, Chet. Uniting Work and Spirit: A Centennial History of Elizabethtown College. Elizabethtown, PA: Elizabethtown College Press, 2001.

Tom enjoys daily conversations regarding living out the Biblical Story with his wife Theresa and their four girls, around the block, at Elizabethtown Brethren in Christ Church (where he teaches adult electives and co-leads a small group), among healthcare professionals as the Northeast Regional Director for the Christian Medical & Dental Associations (CMDA), and in higher ed as a volunteer with the Emerging Scholars Network (ESN). For a number of years, the Christian Medical Society / CMDA at Penn State College of Medicine was the hub of his ministry with CMDA. Note: Tom served with InterVarsity Christian Fellowship / USA for 20+ years, including 6+ years as the Associate Director of ESN. He has written for the ESN blog from its launch in August 2008. He has studied Biology (B.S.), Higher Education (M.A.), Spiritual Direction (Certificate), Spiritual Formation (M.A.R.), Ministry to Emerging Generations (D.Min.). To God be the glory!

Leave a Reply