ESN Writer Mark Hansard interviews John Walton, author of The Lost World of Adam and Eve. See Mark’s review of the book here.

1. Mark: What do you feel are the main themes of the book you’d like people to remember? What’s your favorite part of the book?

John: One of the important core elements in the book is the idea of trying to understand what the Bible’s claims are about material human origins. The dust/rib issue [about what Adam and Eve were made of] is very important because that’s the center of a lot of controversy as Christians try to consider the claims that science makes and try to be faithful to Scripture. So that is one of the main things that I wanted to deal with. I don’t have a favorite part of the book! All the chapters are necessary for building the case.

2. Mark: The idea that Adam & Eve were priests tending sacred space, and that the Garden was a motif for sacred space fits well with your arguments in The Lost World of Genesis One, where you argue that Genesis One is a Temple Inauguration, the ordering of matter for God to inhabit the universe and be worshipped. What inspired you to pursue this thought process? Where did you first get the idea?

John: Well, it’s really a combination of things. I’ve read Ancient Near Eastern literature my whole career and tried to understand it, I encountered things written by other Old Testament Scholars about the importance of the Temple motif, particularly John Levenson’s 1984 article on “The Temple and the World” (Journal of Religion 64 (1984), 275-98). So I was seeing that from the theological side, I was seeing it in the Biblical text and seeing it in the ancient near east.

The main idea of the focus on function rather than material [in The Lost World of Genesis One] came in a flash. I was in the middle of a lecture about Genesis 1 to some advanced Hebrew students and the pieces just fell into place. The direction the conversation went, the questions I was posing, it clicked into place very suddenly. Over the next days and weeks as I was talking to other people about it, I talked to my colleague John Laansma, and he pointed me to his dissertation on “Rest as a Biblical Theme.” That’s when the Temple part came into it.

3. Mark: Your view that Adam & Eve were not the first humans seems quite original. Why do you think it’s important that they weren’t the first humans, and what is the best textual evidence for your position?

John: Well, this idea’s been floating around for quite some time, perhaps the last 150-200 years. And, let’s be clear—I do not say that they were not the first humans, only that the Bible is not making a claim that they were. Therefore, it is not that I consider it “important” that they weren’t, but if the Bible does not claim that they were the first, then we have no argument against scientific views that might pose a problem to their being the first. The strongest textual supports that they may not have been the first and only, are in the fact that Genesis 1 speaks not of Adam and Eve, but of corporate humanity being created, and the presence in Genesis four of those who appear to be outside of the family of Adam and Eve.

4. Mark: Your point that Augustine may have misinterpreted Romans 5 is also fascinating. The idea that we do not inherit sin from Adam, but that it was transmitted to us another way will be surprising to some. Could you discuss some of the different ways early theologians described the spread of sin after the Fall? What has been the reaction of New Testament scholars who have read your ideas?

John: Of course, I am not a NT scholar and so I rely on NT scholars whom I trust and who have persuasive evidence for the points they make. Variations in interpreting the way sin spreads and is transmitted are not new and should not be surprising since the Bible does not address the question. We have learned many important things from Augustine but we have also rejected many of his ideas.

As well, I’m not a church historian, but I’ve read some works that talk about this, for instance Peter Bouteneff’s, Beginnings: Ancient Christian Readings of the Biblical Creation Narratives. He deals mostly with Eastern Christianity before the split with Catholicism. And Irenaeus is one of the main voices that offered other ways of thinking about the spread of sin.

The Bible indicates we’re all subject to sin, but it doesn’t give a genetic theory like we’re all born [with sin] because of our genes and our biology. It doesn’t say we inherit it from our parents. It doesn’t talk about how it happens. It just makes it clear that we are all subject to sin.

5. Mark: I found your discussion in the beginning of the book about ancient cosmology and what the Israelites believed to be a little confusing. If they believed in a structure of ancient cosmology that we know is false today, and that made it into the text of Scripture, what does that mean for the authority of Scripture?

John: In discussions of inerrancy, the distinction is always made between the incidentals in the text that may well accommodate ancient thinking, and the affirmations of the text that represent God’s word. They developed a cosmology based on what they were able to observe (the sky certainly appeared to be solid and the sun, moon, and stars to be located inside the solid sky). But God is not revealing how all people of all time ought to think about the shape of the cosmos. He is revealing himself and specifically his control of the cosmos, regardless of how we might perceive its shape. He used a cosmic geography that they had and they understood, with all of its flaws, to say, ‘However you think about the shape of the world, God’s the one who makes it work.’ He set up our world to function the way that it does, and it’s for us. You can read more about this in my book The Lost World of Scripture, in the chapter on accommodation.

6. Mark: Are there any other points about the book you’d like to make?

John: As I’ve been interacting with people on the book, there’s a very important element that we often don’t pay attention to: When it comes down to it, the most important thing about God creating humans is that God has made us more than what we are made of. And it doesn’t matter if you think we’re made directly of dust, or if you think we were made of amino acids in a primordial soup, or we were made of common ancestry and primates—whatever it is, God has made us more. So we see this pattern with God in the life of Israel. Deuteronomy 26: ‘my father was a wandering Aramean’. Or Ezekiel 16: ‘Your mother is a Hittite, your father is an Amorite.’ The point in both of those places and throughout the Old Testament is that God has made Israel more than what they came from. I think we’ve missed that point. We’re too busy arguing hermeneutics and Hebrew text and evolutionary theory and all those things. For another example, who we are in Christ: we look at 2 Corinthians 5, Ephesians 2: ‘you were some of these things: you were murderers and adulterers. But God has pulled you away from that and the old has become new. And you are not those things any more. You are a new creation.’ This concept is there throughout Scripture, that God has made us more than what we come from, and I would like to have more emphasis given to that idea. In that sense biology is trivial. It’s really not the issue. It’s like talking about ethnicity of the stock of the Israelites. What good is that? It’s what God made of them.

The second point I’d like to make is, when I talk about Adam and Eve as archetypes, and that the ingredients dust and side are archetypal in nature, people seem to have trouble wrapping their brains around that. A good illustration that can help clarify that is something I ran into on the Internet. They were asking second graders, ‘What are mothers made of?’ And one second grader said, ‘Mothers are made of clouds and angel wings and string, and a little dab of mean.’ It’s interesting, because it’s clearly archetypal, even though of course that little girl has a mother who historically is a real person. It’s an archetypal discussion, and furthermore, it uses archetypal ingredients. Angel wings and clouds are archetypal ingredients. And so you’d never ask biological questions of that. How silly that would be! It’s the same thing in the ancient world. Whenever they talk about ingredients, they are archetypal in nature.

7. Mark: At the end of the book, you mention the importance of reaching scientists for Christ, and the barrier that some traditional interpretations of Genesis have posed for evangelism to the scientific community. How do you hope your book will affect evangelism and the future of the Church?

John: I hope that my book will speak to those who either are kept from Christ because scientific ideas are a barrier, and to those who are leaving the church because they perceive the Bible to be in contradiction to a scientific understanding they have found persuasive. When we read the Bible as the ancient text that it is, we can help people to understand that the modern issues that they are struggling with may not be issues that the Bible directly addresses.

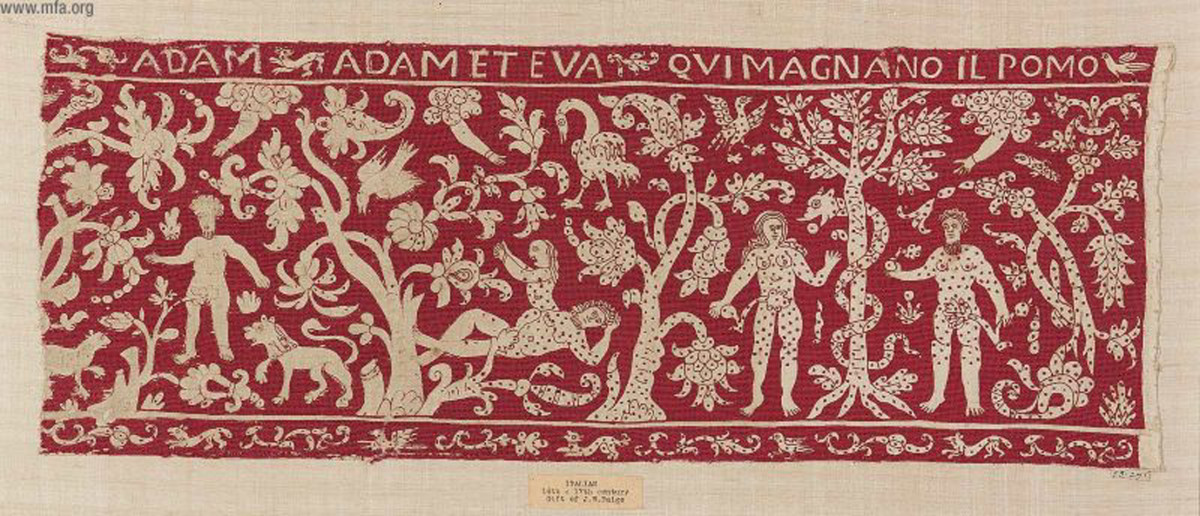

Image credit: Adam and Eve, from Art in the Christian Tradition, a project of the Vanderbilt Divinity Library, Nashville, TN. http://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/act-imagelink.pl?RC=50217 [retrieved November 14, 2015]. Original source: http://www.mfa.org/.

Mark is on staff with InterVarsity Christian Fellowship in Manhattan, Kansas, where he ministers to Faculty at Kansas State University and surrounding campuses. He has been in campus ministry 25 years, 14 of those years in faculty ministry. He has a Master’s degree in philosophy and theology from Talbot School of Theology, La Mirada, CA, and is passionate about Jesus Christ and the life of the mind. Mark, his wife and three daughters make their home in Manhattan.