I’ve generally felt it is worth making a distinction between the brain and the mind–the mind is what is mediated by the brain. I’m inclined to affirm free will and think our conscious self is capable of top-down causation. I don’t know how or if that version of a mind maps to Biblical nouns like spirit and soul, and I wonder to what extent we are obliged to affirm those precise categories as Christians and to what extent they were the closest available options in Greek metaphysics of the time. I tend to attracted to pursuits of the mind. That’s the background I brought to this philosophical essay on why we’d be better off without the concept of the mind, and to my surprise I found myself not entirely opposed to the proposition.

The section I found most compelling was the discussion of psychiatry and the harm associated with the concept of mental health. I recognize the stigma associated with both the diagnoses and the treatments we associated with mental health. I agree that there is a tendency to treat both as somehow not real, or less real; pills and surgeries count as fixes in a way talking does not. “Less talking, more doing.” “Actions speak louder than words.” And so on, all implying that talking is not an action, talking is the opposite of getting something done. So when Joe Gough writes about patients feeling like they are being brushed off when they are prescribed talk therapy for chronic pain, I can see what he’s getting at.

Previously, I would have said the solution is to defend the ontological reality of the mind. Psychiatric therapies have value because the mind is real and has causal power. Maybe that’s a little easier for me to accept because I spend so much time programming computers. I tend to think of the code I write as something abstract and nonphysical which nevertheless brings about physical results, most concretely charts I can see and print. But I suppose I could just as easily make the argument that I physically type on a keyboard, which causes electrons to move around in the memory chips to store my code. When I then run the code, more electrons move around in the processor, causing magnetic elements to move on the hard drive, and ultimately light to be emitted from the monitor to display the result, or ink to be placed on paper. That wouldn’t help me do my job better; at the level of electron movements, I don’t know what needs to be done to accomplish the results I want. But there are physical processes involved all along the way, and maybe my detachment from them impacts how I think about other systems.

So maybe I’m not adequately considering the challenges associated with the mind concept. Maybe instead of doubling down on the reality of the mind, we’d achieve better health outcomes if we set aside the mental health category and used psychiatric terminology instead. When it comes to health, I’m open to pragmatic approaches. Of course, widespread language changes are not easy, but they do happen when enough people want them to. Beyond the challenge of persuading people, I wonder what happens when we want to speak collectively of all the activities or functions that Gough lists out separately: cognition, imagination, agency, memory, and so on. I’d guess that at some point we’ll want to do so, and without a substitute we’ll fall back to mind and mental. Brain functions or nervous system functions are obvious options in some respects, but I expect those will yield too much to materialism for some, while also excluding the role of other body systems like the immune system. Do you have any suggestions?

Of course, in a Christian context we also have the question of what to do with the exhortation to love God with all our minds? From my layman’s understand, the Hebrew word more literally means heart, and the Greek word used in the New Testament when Jesus quotes the Deuteronomy refers to a specific kind or process of thinking. Neither seems to obligate translating to ‘mind’ exclusively, and if we had never had that word in English we would have still options. Bigger picture, the sentiment of the commandment is about loving God with every aspect of ourselves, and here again I think we could get across that concept even if only had more granular options. But I am neither a theologian nor a scholar of these languages, so I may very well be overlooking an important Biblical reason to hold on to the mind as a concept.

Do you think the concepts of mind and mental are helpful? Did any part of Gough’s discussion seem persuasive? How would you propose changing our terminology, if at all?

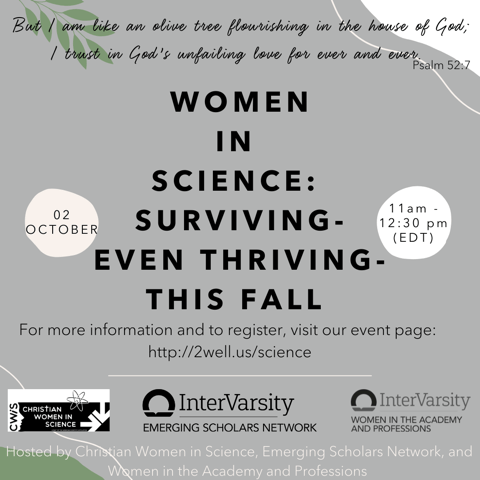

If you are a woman in science, or think you might want to be, check out this upcoming online event. And if that’s not you, share with someone who is.

Andy has worn many hats in his life. He knows this is a dreadfully clichéd notion, but since it is also literally true he uses it anyway. Among his current metaphorical hats: husband of one wife, father of two teenagers, reader of science fiction and science fact, enthusiast of contemporary symphonic music, and chief science officer. Previous metaphorical hats include: comp bio postdoc, molecular biology grad student, InterVarsity chapter president (that one came with a literal hat), music store clerk, house painter, and mosquito trapper. Among his more unique literal hats: British bobby, captain’s hats (of varying levels of authenticity) of several specific vessels, a deerstalker from 221B Baker St, and a railroad engineer’s cap. His monthly Science in Review is drawn from his weekly Science Corner posts — Wednesdays, 8am (Eastern) on the Emerging Scholars Network Blog. His book Faith across the Multiverse is available from Hendrickson.

Leave a Reply