I’ve been working through some thoughts left over from my reading of James Davison Hunter’s To Change the World: The Irony, Tragedy, and Possibility of Christianity in the Late Modern World. This is probably my last post on this book, unless, of course, I think of something else.

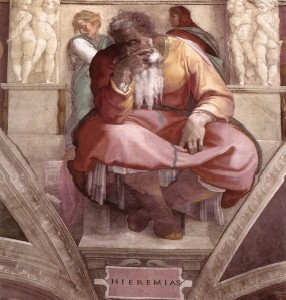

In searching for a new paradigm for Christian engagement with the world, Hunter suggests Jeremiah 29, God’s word to Israel as they were about to go into exile among the Babylonians. Jeremiah 29:11 is the most often quoted verse from this chapter (“For I know the plans I have for you…”), but Hunter focuses more on God’s instructions to Israel in Jer. 29:4-7:

This is what the LORD Almighty, the God of Israel, says to all those I carried into exile from Jerusalem to Babylon: “Build houses and settle down; plant gardens and eat what they produce. Marry and have sons and daughters; find wives for your sons and give your daughters in marriage, so that they too may have sons and daughters. Increase in number there; do not decrease. Also, seek the peace and prosperity of the city to which I have carried you into exile. Pray to the LORD for it, because if it prospers, you too will prosper.”

Hunter sees this passage – in which God urges Israel to work and pray for the prosperity of Babylon – as paradigmatic for our times. He draws on 1 Peter and other New Testament passages that also carry the theme of exile.

Though it is quite possible that this portrayal from Jeremiah is not applicable to Christians in all times and all places, I do believe this is a word for our time. The story of Jeremiah comports well with what we learn from St. Peter, who with so many others speaks of Christians as “exiles in the world” (1:1, 2:11) encouraging us to “live [our] lives as strangers here in reverent fear” (1:17). God is at work in our place of exile, and the welfare of those with whom we share a world is tied to our own welfare. (Hunter, 278)

Hunter further cites 2 Thessalonians 3:13, Philippians 2:4 and 4:5, and 1 Corinthians 12:7 for Paul’s directions to work for the good of people around us. Hunter uses these Biblical models to suggest the idea of the “new city commons”:

In short, commitment to the new city commons is a commitment of the community of faith to the highest ideals and practices of human flourishing in a pluralistic world. (279)

Hmm…”human flourishing” —where have I heard that before?

So, here’s my question: Is exile the best paradigm for Christians in the university?

There’s much to applaud in exilic model of Jeremiah —living faithfully in a pluralistic society, working for the common good, being a “faithful presence” while acknowledging the tensions that pull us away from faithfulness. On the other hand, I saw a recent blog post (which, overall, was so bad that I’m not going to link to it) raised a good question: considering how influential Christians have been in shaping and building American culture, how accurate or even helpful is it to call ourselves “exiles”? Isn’t it a way of denying the vast power that we hold in various cultural institutions?

What do you think? Is exile the best paradigm for considering the state of Christians in academia?

Photo credit: Missional Volunteer via Flickr

The former Associate Director for the Emerging Scholars Network, Micheal lives in Cincinnati with his wife and three children and works as a web manager for a national storage and organization company. He writes about work, vocation, and finding meaning in what you do at No Small Actors.

Leave a Reply