How can Western missionaries avoid creating imbalances of power between themselves and those they’re serving, and how can missionaries prepare for situations of disagreement with humility? The Urbana Missions Conference connects students with missionaries to encourage and develop sharing the gospel globally. This seminar addresses how Western missionaries can use their financial, educational, and cultural capital to empower, rather than dominate local environments.

From Dec 27 – Jan 1, volunteers with our network of early career Christian academics are liveblogging seminars at the Urbana conference, a mission-focused student gathering of 16,000 Christians from across North America and the world. Due to personal reasons, the speaker has requested not to be identified. Since information in this seminar may be sensitive in nature, specific names and locations are not included.

The speaker opens the session by describing the “postcolonial critique” of missions, an academic conversation in which missions and evangelism are linked to oppression. This seminar is about learning from the history of this critique, rather than critiquing it. The seminar’s goals are:

- define what’s valid about the critique

- determine our response as Christians and missionaries

- discuss how to approach missions differently as a result.

“We want to be inheritors of those that come before us,” says the speaker, “ to learn from both their successes and their mistakes.”

Postcolonial Critiques of Western Missions

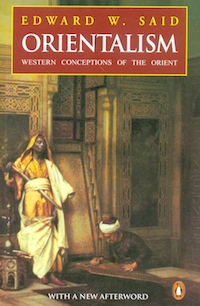

The speaker cites the book Orientalism, by Edward Said, as a conceptual starting point of postcolonial critique. The book describes how the Western world defines itself as opposite to the east, a place of exotic language, culture, and mystery. The book criticizes social sciences as interwoven and complicit with Western colonial efforts, and emphasizes that our own biases and perspectives inform our views of people groups.

The speaker cites the book Orientalism, by Edward Said, as a conceptual starting point of postcolonial critique. The book describes how the Western world defines itself as opposite to the east, a place of exotic language, culture, and mystery. The book criticizes social sciences as interwoven and complicit with Western colonial efforts, and emphasizes that our own biases and perspectives inform our views of people groups.

What is postcolonialism?

Prefaced as a broad overview, the speaker defines post-colonialism as “the oppressed reacting to colonization.” Post-colonialism emphasizes the empowerment, or agency, of the colonized, and points to the mutualism between colonizers and colonized. Finally, post-colonialism “unpacks dynamics of power,” which tries to stay in power through different techniques. The speaker cites Evangelical Post-Colonial Conversations as a helpful source for evangelical engagements with this idea.

How can we learn from post-colonial critiques?

The speaker acknowledges the tragic truth that “missions and violence often went hand in hand.” He continues: “We need to come to the table with humility, these things happen. We are the inheritors of these tragic truths” He describes the conflation of the lack of the gospel with the lack of civilization. He points out that “theology is not this abstract or neutral thing, but is linked to people’s position and privilege,” especially regarding money and power.

5 Practical Ways to Learn from Postcolonial Critiques of Missions

The speaker offers five suggestions for responding to the legitimate critiques of Christian missions.

1. “We need to look at our perception of the word ‘other.’ We were very concerned that veteran missionaries described the locals using negative terms. When you’re in a culture different than yours, you start to focus on the particular things you dislike and start to build a narrative about a people group.” He describes how he adopted Matthew 10:16 as a reminder of his role in empowering local culture: “I am sending you out like sheep among wolves. Therefore be as shrewd as snakes and as innocent as doves.” He reminds us to focus on what aspects of local culture were more godly than in the U.S.

2. “We want to see that missions is an opportunity for us to invite the marginalized to speak.” In the case of missions, “we’re not doing the world a favor. We need to hear those voices to build the global church.”

3. Our activities aren’t only converting others, but deepening our own conversion. “In evangelical theology, there’s a point conversion at which a person becomes a Christian. We need to add to it by pursuing our own deepening conversion!”

4. We can respond through deeper cross-denominational and organizational partnerships. “When we minister as part of a particular organization or denomination, we’re taking with us particular ways of doing things,” he says. “When we’re in the mission field we don’t have the luxury of ministering in a single way, for the simple reason that there’s not enough people.” He stresses asking what’s the essential reason we’re here – not for our own organization, but for people to encounter Jesus.

5. “Respond by having a posture of redistributing power and re-negotiating power hierarchies. Missions can be about giving away control and giving away power.” He describes three aspects of power: resources, language, and position.

The speaker argues that “language is power. Communication is power. Language learning will make you feel like a child, especially in context rather than in a classroom. Ministry in a local language redefines power dynamics.” By using local languages, we put ourselves in a position to be humiliated and shamed. “We had to struggle at learning language because we wanted them to be in a power position,” he describes. The person with language can argue and make decisions. The speaker emphasizes bible translation as the number one missionary endeavor. A translated, readable bible, and a local bible study puts the power to theologize in local hands.

Power and position describes who decides what the ministry looks like. “We are the outside missionaries, we have the organizational affiliation, and we want this to be a community decision.” It’s not as simple as giving all decision making power to locals, or foreign missionaries. “The point is that we have to engage with each other and get into the mess of it all to hear all the voices that are in ministry together.”

Finally, power and resources describes finances, networks, and access to ministry. Because resources can be used as power, he questions “how can we steward the networks the Lord has put us in touch with? It’s not that simple, because we don’t want to come in as wealthy Americans to dump resources on poor people.” It’s about taking appropriate risks, the speaker describes, it requires a partnership of resources.

Learning To Navigate Power Differences from the Epistle to Philemon

The speaker asks us to look at the book of Philemon. There are three main players: Paul, as ecclesial power; Philemon, as holder of local power; and Onesimus, as a slave and holder of local power. In the book, Paul advocates Onesimus and respects all parties as equal decision makers.

Resources for Further Study

- Sanneh, L. (2003). Whose Religion Is Christianity?: The Gospel beyond the West (4th edition). Grand Rapids, Mich: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.

- Chan, S. (2014). Grassroots Asian Theology: Thinking the Faith from the Ground Up. Downers Grove, Illinois: IVP Academic.

- Moe, D. T. (2015). Evangelical Postcolonial Conversations: Global Awakenings in Theology and Praxis. International Bulletin of Missionary Research, 39(4), 243-245.

- Twiss, R. (2015). Rescuing the Gospel from the Cowboys: A Native American Expression of the Jesus Way. InterVarsity Press.

Q/A

What do you think about the general presence of white people in developing countries, and how their presence can cause issues?

I encounter this in secular academics. But everyone will make mistakes, and these issues are difficult to solve abstractly. “I think we have to improve our missiology while we’re on the mission, though there will be some errors. I don’t see any other way than getting out and going for it, doing it in humility, with partners, with people that will correct you, and with locals with whom you can build trust.”

All of this fits into long term missions, but what about short-term missions?

“You have to surrender your agenda,” and trust that those in the long term see the broader perspective. “Focus on friendships,” because people expect you to share the gospel already. “Because of the Internet, use what you do in the short term to build a relationship,” because social media allows you to continue them.

How can a young missionary organization going to a developing world avoid creating problems while helping the poor?

Learn from those who are there, and if there are none, build relationships with local leaders. Don’t move until those relationships are built with mutual trust, and let them discern what will happen. It requires understanding the country and the history of missions there, as well as the role of the West in that country’s economics.

What’s your stance on translations in regards to cultural differences, such as father vs. mother, etc?

It’s a hot issue! Translation is never finished, but needs to be critically engaged and updated over time. Be open to translations, rather than be one sided. Take the risk and let the locals whose heart language it is make those decisions. People over time have had relationships with God through different, fluid translations.

How do you collaborate with other missionaries with traditional views?

What are essential issues, and what are timing issues? When do you fight the battle? But learn to have fellowship with people that don’t have completely overlapping values. Trust that the Lord will bring other people into your life.

How can this postcolonial missiology inform other scholars?

Read Whose Religion is Christianity! Bible translation is liberating and empowering for local translations, because once it is translated, people are free to start theology, church, and discipleship based on how they view the word. There’s small ways to share the other side of the story – that missions CAN empower and preserve culture, though it can oppress, and has much of the time. At the appropriate times, raise the voice.

Angelo is a 2016 graduate of the University of Illinois, where he focused on Molecular Biology and Asian American Studies. He’s interested in intersecting several fields: bioinformatics, microbiology, minority studies, digital humanities, and the role of faith as an academic. He has recently joined InterVarsity Christian Fellowship as a Digital Spaces staff member.

Leave a Reply