There was a lot of talk about “proof” in the news this month. The Ken Hamm/Bill Nye debate captured a lot of attention and raised questions about what science can prove about particular creation models, and even about what kinds of evidence are acceptable or reliable. There was an interesting story about a computer-generated math proof that required 13GB of reasoning, far too much for human beings to parse through and verify, which led to questions about the limits of what can be proved in mathematics and whether math will ultimately become the domain of computers. Meanwhile, an archaeological paper about camels led to a lot of headlines about the Bible being contradicted or perhaps even proven false.

All of this stirred up some of my own thoughts on what can (or cannot) be proved about God. For many Christians, it seems desirable to have logic or philosophy or science prove that God can or must exist. And yet empirically, it would seem that one consequence of pursuing such proofs is that we raise the possibility that God is potentially falsifiable. So naturally some folks become interested in proving God can’t or doesn’t exist, which seems to result in the perception that findings like the timing of when camels arrived in Palestine can falsify the Bible, and possibly by extension God. If the outcome of our attempts to prove that God can or must exist is to cause people to misunderstand the nature of the Bible or the nature of God, then perhaps we need to reconsider the claims we make. For instance, what if we instead tried to prove that God’s existence is somehow formally undecidable?

What would such a proof look like? The following is more of a sketch or an outline of a proof, or some musings that could perhaps one day be formalized; they are the thoughts that I’ve had on the topic and I’d be curious what other folks make of them.

First, let’s consider what axioms we can choose. We could start by assuming there is no God, in which case there is nothing to prove. Likewise for the assumption that there is a God. So the only interesting choice is if we assume that God is a possibility, or choose a set of assumptions that don’t explicitly say anything about God one way or the other. I suspect there are a range of ways to formalize that idea, but I think the notion of God as a possibility is sufficient for our purposes.

Now, we need to know what we mean by God. One way we describe God is that He is infinite. Here, I take that to mean that it would require an infinite amount of information to accurately describe God and His works. (This is admittedly a potential point of departure for some, but we need some formalization of what we are talking about and this one makes sense to me.)

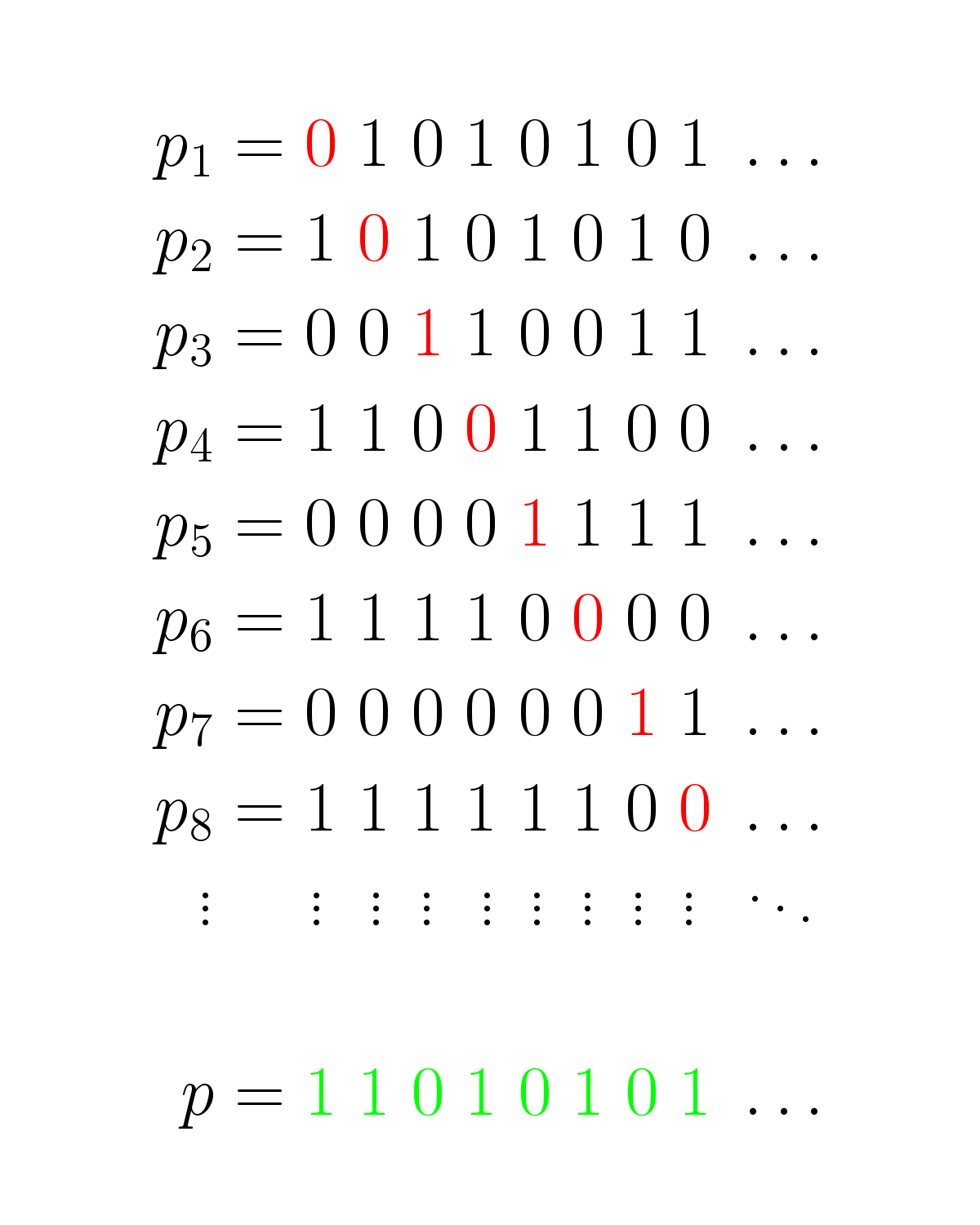

Then let’s say we have some proofs that God does not exist. Let’s put them in some kind of order, maybe the order in which they are proposed. Each of these proofs must define the God they are disproving, and information theory says we can express that definition of God as a sequence of 0s and 1s (or bits). So now we have a big list of such sequences, each of which disproves a particular definition of God. But now we go down the list, and if the first bit of the first sequence is a 0, we choose a 1, and if the second bit of the second sequence is a 1, we choose a 0, and so on. After we are all done, we will have a description of God which is different than all of the other sequences, and thus it is a definition of God that has not been disproven. This suggests to me that one cannot disprove the existence of an infinite God.

But just because we cannot disprove the existence of an infinite God doesn’t mean we can prove it. In a finite amount of time, our definition of God that we are proving can only be finite, which means that the best we can do is prove a finite approximation of an infinite God, which, since the approximation is finite, does not really prove anything about an infinite God.

The combination of these two lines of reasoning at least suggest to me that an infinite God is in fact an undecidable proposition for finite beings, rather than being provable one way or the other.

Now, what are the implications of this conclusion? Well, an interesting consequence is that the probability of us finding the correct (finite, approximate) description of an infinite God among the infinite possible descriptions is vanishingly small. That might seem disheartening, but it implies that if such a God wishes to be known by finite beings, then He will have to initiate that process. And this is exactly what the Bible teaches — that we would never know God if He had not reached out to us. A provable God would have no need to do so, because we’d eventually work out the proof. And a God that provably does not exist wouldn’t exist to reach out to us. And so it would seem to me that the story of scripture is most consistent with a God whose existence is formally undecidable.

Andy has worn many hats in his life. He knows this is a dreadfully clichéd notion, but since it is also literally true he uses it anyway. Among his current metaphorical hats: husband of one wife, father of two teenagers, reader of science fiction and science fact, enthusiast of contemporary symphonic music, and chief science officer. Previous metaphorical hats include: comp bio postdoc, molecular biology grad student, InterVarsity chapter president (that one came with a literal hat), music store clerk, house painter, and mosquito trapper. Among his more unique literal hats: British bobby, captain’s hats (of varying levels of authenticity) of several specific vessels, a deerstalker from 221B Baker St, and a railroad engineer’s cap. His monthly Science in Review is drawn from his weekly Science Corner posts — Wednesdays, 8am (Eastern) on the Emerging Scholars Network Blog. His book Faith across the Multiverse is available from Hendrickson.

Hi Andy,

Thanks for the post – I just thought I might chip in with a few thoughts about the mathematics and the diagonal argument you use. (BTW, I assume when you say ‘disprove an infinite God’ you mean existence?)

Beginning with the most mathematical points…

– There is a problem with simply taking the diagonal sequence as a counterexample, as this may not be a valid argument/description in the encoding used.

– The diagonal argument depends on these sequences being infinite in length. If we say that any proof/description should be expressible in finitely many symbols (so that we could potentially read it) then there is no problem (as there are only countably many finite length sequences). Similarly while these arguments may not exclude all meanings of ‘God’, they may exclude the type of God we claim to know – to draw an analogy, even in the presence of all the mathematical paradoxes out there, you can prove that there are no real numbers a and b such that a+b > 2 max(a,b).

– Why should our arguments be expressible using only a finite alphabet? Why not allow an uncountable alphabet? Why not a continuum of statements? The informational content of these is no longer expressible in bits, but this is not a problem mathematically. The argument then becomes a bit more delicate, and depends on to what extent you accept Cantor’s conceptions of infinity, the axiom of choice, etc…

– The encoded arguments you consider are exactly that – encoded, and do not in and of themselves have meaning. As the statement “01110100110110000” is meaningless without some hermeneutic which allows you to interpret what is meant by these symbols, the formal statements considered are an incomplete description of the argument. Godelian paradoxes abound if you try and reduce the hermeneutic to the status of another encoded theory, so this is probably not the best way forward.

– I wonder whether this argument effectively denies common sense logic. Let me assume, given Quantum uncertainty etc, that there exists no sequence of real numbers (equivalently, no sequence of sequences of bits) which completely describe the Mona Lisa. Suppose I wish to prove to you (or the police) that I do not possess this painting. Then, by your argument, there is no way I can do so. Even saying “It’s in the Louvre” doesn’t work, as it is impossible for either of us to determine conclusively that this is the painting we are discussing.

Finally, I wonder whether this logic of ‘proof’ is really what we are looking for here. There are very few things that we can prove, and this is not how we live or act. For example, the formal status of the statement “I have a brother” is irrelevant if I introduce you to him. Perhaps this is a better model for us understanding these issues?

Sam,

Thanks for chipping in!

First, I am fully in agreement with the sentiment of your final point. I’m not sure that the language of proofs is really the most helpful when it comes to the question of God’s existence, but lately I haven’t been able to escape the reality that lots of folks do expect there to be a rigorous proof one way or the other. So I thought I’d try to flip that expectation around and ask the question “What if the only thing we can rigorously prove about God’s existence is that it is undecidable?”

So yes, I agree that formal proofs don’t reflect the way we actually think about most things, nor the Biblical model of how we come to know anything about God.

Nevertheless, I also think the concepts involved in my “proof” are fun to think about, so since you took the time to comment on some of the details, I’m happy to explore those points further. You raise a lot of good ones; some of them had occurred to me but I elided over them because I didn’t want to get bogged down in details, and some of them have given me knew things to think about. In your same order:

– My notion was that each sequence represents a description, or model, of God, which needs to capture the infiniteness of God. I chose to assume this would mean an infinite sequence – ultimately this is an assumption and I’m not entirely sure how to defend it. I agree it is a critical point that would need further elaboration for a real formal proof, but at this point asserting it as an axiom is the best I can do. However, this doesn’t mean the description or model itself needs to be infinite. What I have in mind is something like the Fibonacci sequence – we can define the sequence very compactly, but it expands out to an infinite sequence.

And yes, even if my proof held it wouldn’t prove that a specific model of God couldn’t be disproven (in fact it assumes that is possible), and so Christians could still be dissatisfied with particular outcomes. But since most attempts at proving the existence of God don’t get as far as proving the God of the Bible either, so I think there’s an equivalence there as far as Christians are concerned.

– Yeah, I was trying to avoid the axiom of choice. 🙂 I am familiar with the concept of different cardinalities of infinite sets, but I’m not entirely sure I understand what it would mean for the argument to be expressed in an uncountable alphabet. My first reaction is to think about the 13Gb math proof I referenced – that’s a proof of finite length over a finite alphabet, and it’s not entirely clear how to even verify that, so I’m not sure what we could do with an argument expressed in an uncountable alphabet. I’d have to give this one more thought.

– My initial thought on the encoding issue is that perhaps it is sufficient to assume that (1) an encoding exists and (2) all the arguments can be expressed in the same encoding. But that’s probably overly simplistic. My next thought is that, on some level, I’m trying to trigger a Gödelian paradox rather than avoid one, so maybe this isn’t a problem.

– Actually, the Bekenstein inequality says that because the Mona Lisa occupies a finite amount of space which contains a finite amount of energy, then there is a finite limit on the amount of entropy in that space, which means only a finite amount of information would be needed to describe it. Thus the same argument does not apply to the existence of every day objects.

And finally, since we’re here, the other detail I knowingly glossed over was whether or not an arbitrary sequence of 0s and 1s represents a valid and distinct description of God — maybe the sequence I constructed is nonsense. Unfortunately at this point all I am prepared to say is that I recognize the need for more work here if this proof were to be actually formalized.

Thanks for giving me a lot to think about!

Two thoughts

Can we know accurately but incompletely. I know my wife quite well after many years together but I do not know her comprehensively. e.g. how many cells, what is her blood pressure over time, etc. In fact anything we know is only known in this way. I can’t know any object comprehensively – just think a bit about Heisenberg and the location of all the electrons involved. The penny in my pocket is a 1997 D Lincoln penny, but who all has touched it? What is its actual weight?

What of the leaky bucket theory – this loosely corresponds to the series of 1s and 0s. if there is a leak in my argument A, and another in B and another in C, if I stack the buckets, will they then hold water? this was actually an argument I heard at the seminary level in an apologetic class.

David,

Thanks for sharing your thoughts!

To your first question, I would definitely affirm that we can know accurately even if incompletely. I’m not trying to say that we can’t know anything about God, and in fact I believe it is possible to know God and that the Bible contains accurate (if perhaps incomplete) information about God.

But knowing something is different from being able to prove it via rigorous deductive or mathematical reasoning. As both you and Sam allude to, rigorous proof isn’t not something required in much of every day life, and I’m quite content with that, even when it comes to matters of theology. My primary interest in the proof is actually to provide a counterpoint to the expectation that God’s existence can be rigorously proved or disproved. (My secondary interest is an excuse to exercise my mind and push the boundaries of my understanding on topics like Gödel’s incompleteness theorems.)

To your second question – I think there is an analogy there, yes. Although I think if I were going to express my argument in terms of buckets, I would use overflowing buckets. Each bucket can hold the description of God that it disproves, but what spills out of it are all the descriptions that it does not disprove. If the spring of water filling the buckets never runs dry, then no matter how many buckets there are, they will all overflow.

As a mathematician by training, I think I actually find it more difficult to understand proofs that involve “fuzzy” ideas, like people. If I’m to understand you correctly, we can’t prove God exists because all our descriptions will be finite, and we can’t prove God doesn’t exist because we would have to describe him. I liked your idea about listing out all possible descriptions and then proving that you can’t, hence that you can’t disprove God’s existence. My only possible objection, then, is that it might be possible to prove or disprove God’s existence without having to describe him.

Nadine,

So, I think your “fuzzy” comment is quite apt. It’s not entirely clear to me that any proofs of God’s existence or nonexistence provide a definition of God that is sufficiently robust to allow for a proof of the desired level of rigor. Thus we are left with more fuzzy reasoning by analogy, which admittedly is at best all I have achieved here; such reasoning may be persuasive to some, but not conclusive for all.

Your notion that the question of God’s existence could be settled without describing him is an intriguing one. You’d still need some kind of definition, though, otherwise when you’re done how do you know what you’ve proved? Do you have an idea of what would represent a workable definition that is distinct from the kind of descriptions I described?