(Image by Sami Aksu at Pexels)

That infamous line from Star Wars is just one of many popular suggestions that truth is in the eye of the beholder. “One man’s trash is another man’s treasure.” “Missing the forest for the trees.” The film Rashomon and its numerous imitators. The parable of the blind men describing just the part of an elephant they can touch. The meme of two people standing on either side of a numeral which could either be a 9 or a 6. Our language and our culture are rich with illustrations of how perspective and perception shape our understanding of the world. In many circumstances, we are well-served if we grant that another person’s point of view is both valid and substantially distinct. But have we constructed a garden path leading us to conclude that all truth is up for debate?

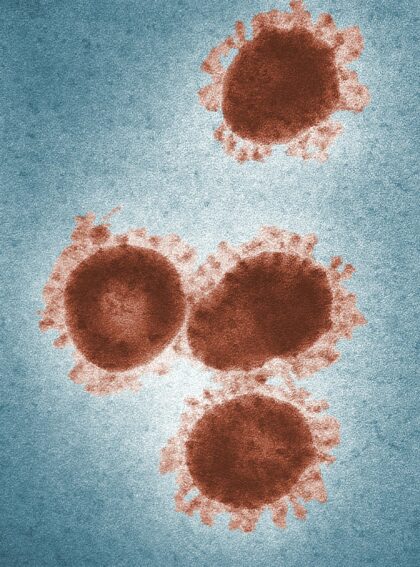

We seem to be in a bit of a renaissance for miasma theory, the idea that diseases are caused by bad air or other environmental factors. This is contrasted with germ theory, the idea that diseases are caused by specific infectious agents. One might also toss in an element of a modern form of humoral theory, the idea that disease is a result of imbalance in the body. In the history of medicine and biology, all of these had serious supporters and were motivated by engagement with empirical evidence. Are these alternatives merely matters of perspective, different interpretations of the same data?

One doesn’t have to be a quack or a science denier to recognize that science can be subject to the ebb and flow of fashion. In the world of interpretations of quantum physics, we’ve got the Copenhagen interpretation, Everett’s many worlds, de Broglie and Bohm’s pilot wave model, and at least a half dozen others, each with their enthusiasts. Those trying to unify general relativity with quantum physics can opt for string theory or loop quantum gravity. Dark matter options come in hot, warm, and cold varieties, plus the buffet of alternative formulations of gravity. It is not hard to imagine how even a well-informed layperson could get the impression that science is more about picking a team and rooting for it than finding definitive answers.

But even in sports, we don’t just sit around and debate which team is better; we play the games. In science, the “game” is all about gathering new data to differentiate between the options. To be sure, a lot of press goes towards cutting edge physics, where we don’t yet have the data to decide, say, loops or strings. But the work of science is not primarily playing the partisan and crafting rhetorical arguments from existing data (although some amount of that can happen when applying for the funding to pay for gathering the new data or when recruiting new students). The main work of science is figuring out how to frame a question precisely enough that we can get an answer one way or another–and then actually asking the question through observation and experiment. Once the data are in, we don’t have to keep debating in the same way that we did when we lacked information.

When it comes to the causes of disease, we have already designed and carried out the experiments to collect more data and answer many questions. For example, we have data to differentiate between the hypothesis that the measles virus causes measles and the hypothesis that the measles virus grows opportunistically in people whose bodies were already in a diseased state. If all we had were observations that the virus was present in measles patients and not present in healthy people, both hypotheses would be plausible explanations consistent with the data. But we can go beyond that and apply Koch’s postulates (in an animal model, for ethical reasons) or other logically comparable experimental tests. And we can do something similar with treatments for diseases, to rule out or at least render highly unlikely the possibility that people who received a treatment just coincidentally got better.

We can also elaborate on details and get more precise. Typically when we say pathogen X causes disease Y, what we mean is that pathogen X is necessary–you can’t get disease Y without X–while the question of sufficiency might remain open. For example, the measles virus is necessary to get the measles, but one could make the case that it is not sufficient because people who are immune, either from vaccination or prior infection, can be exposed to the virus without getting the measles. Or with HIV and AIDS, the virus is necessary, but since people with the CCR5Δ32 mutation can resist infection–a mechanism different from being immune–one could say it is not sufficient. There can also be some cases where a pathogen might be sufficient but not necessary, such as human papillomavirus which causes many but not all cases of cervical cancer.

However, just because a pathogen is necessary to cause the disease doesn’t mean there aren’t other factors which can contribute to risk of exposure or to severity of disease once exposed. It is absolutely the case that a substantial contribution to public health in the past century or so was improved sanitation and hygiene practices, which can reduce rates of diseases like polio and cholera. While one could describe this as more in line with miasma theory, it is also completely consistent with the germ theory explanation that the poliovirus and Vibrio cholerae cause those respective diseases. Those particular pathogens are shed in feces, so improved sanitation reduces the opportunities to come in contact with them. Similarly, vitamin supplements were a boon to public health in populations with vitamin deficiencies, which one could describe as resolving an imbalance in the body. And in some cases, vitamin deficiencies can worsen the results of infectious diseases like the measles, since the body lacks the resources to fully muster an immune response; then, a vitamin supplement can help. But you still have to get the measles virus to get the measles in the first place, you can still have a bad or even fatal case of measles even if you have sufficient vitamin A, and you can still avoid serious illness by getting vaccinated and preventing infection in the first place even with low vitamin A.

It is probably also worth noting that some diseases do have primarily or exclusively environmental causes, including bad air. For example, inhaling asbestos is causally linked to certain lung cancers, and the toxic dust from the 9/11 attacks has been associated with a number of diseases. Other diseases like diabetes result from internal disregulation; this is not strictly humoral theory since insulin is not one of the four humors, but that kernel of the importance of balance and regulation persists in our modern understanding of homeostasis and autopoiesis. But we know these things because we collect the data specific to each disease, not because we favor one theory of disease in all cases to the exclusion of the others.

And so while different models apply in different combinations to different diseases, we aren’t exactly back to the elephant parable. We do not have to accept some sort of vague amalgation of all the options, or align with just one on the rationalization that it’s the truth from our perspective. As a scientist, what the story says to me about scientific issues is (1) there is an objective reality external to our subjective experience and (2) when faced with discrepancies, gather more data.

Andy has worn many hats in his life. He knows this is a dreadfully clichéd notion, but since it is also literally true he uses it anyway. Among his current metaphorical hats: husband of one wife, father of two teenagers, reader of science fiction and science fact, enthusiast of contemporary symphonic music, and chief science officer. Previous metaphorical hats include: comp bio postdoc, molecular biology grad student, InterVarsity chapter president (that one came with a literal hat), music store clerk, house painter, and mosquito trapper. Among his more unique literal hats: British bobby, captain’s hats (of varying levels of authenticity) of several specific vessels, a deerstalker from 221B Baker St, and a railroad engineer’s cap. His monthly Science in Review is drawn from his weekly Science Corner posts — Wednesdays, 8am (Eastern) on the Emerging Scholars Network Blog. His book Faith across the Multiverse is available from Hendrickson.

Leave a Reply