It’s Nobel Prize week, but since those announcements are in the future for me, I’d like to go back a month to the 2024 IgNobel prizes. While they might seem at first glance like the Razzies for science, the IgNobel awards are more celebratory and seek to spotlight science which is rigorous but not quite as prestigious in its applications or aspirations. And yes, sometimes there is a bit of a scatological bent, but even our baser bodily functions need to be understood with clarity. The prize that stood out to me was less potty and more potted, however–the Botany Prize which went to Jacob White and Felipe Yamashita for their work on plant mimicry.

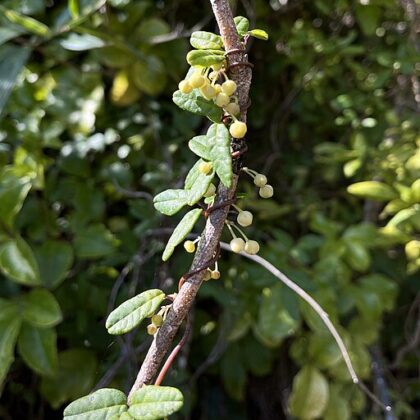

I actually thought I might have covered this research already, because it sounded familiar. Turns out, I had written about the science which provided the background to White & Yamashita’s study. While writing about the book The Revolutionary Genius of Plants, I highlighted the discussion of Boquila trifoliolata. This is a plant that can mimic the leaves of the plants around it, boasting a fairly impressive repertoire and fidelity. One vine can even have leaves resembling those of multiple different surrounding plants. This mimicry helps to keep it from being eaten; it takes on the appearance of toxic plants that foragers have learned to avoid.

How does it know what the other leaves look like? One possibility is that it senses unique chemicals emitted by the other plants and has learned what shapes correspond to which plants. Such an association could plausibly evolve; different B. trifoliolata individuals could start with random associations, and the ones that matched the best would gain an advantage they could pass on to more descendants. This option would essentially amount to smelling the other plants.

Another option is horizontal gene transfer, such that the B. trifoliolata wind up with genes from the surrounding plants, possibly by way of a microbial intermediate. If the shared genes controlled leaf shape, B. trifoliolata could just express them directly to get the right shape. Alternatively, as long as the shared genes are unique to the other plant, they could serve as an identity marker similar to the airborne chemicals and then we’re back to the challenge of associating leaf shapes with signals.

More intriguing is the possibility that B. trifoliolata just looks at the other leafs and copies them based on what it sees. B. trifoliolata doesn’t have eyes like humans, nor does it have a nervous system that could support a visual cortex like ours. But it could have ocelli, simple eye-like structures that can respond to light. It would not necessarily require a sophisticated processing system to detect the light-and-dark pattern from the shadow of a leaf and reproduce that pattern in a growing leaf. But we cannot even read the minds of other humans; how do we know what a plant is seeing, if anything?

That’s where the recent work by White & Yamashita comes in. They grew B. trifoliolata in the presence of plastic leaves and observed evidence consistent with the plants mimicking the artificial shapes. Horizontal gene transfer definitely cannot be the cause in that case; plastic plants have no genes at all to share. Artificial plants likely evaporate some chemicals which could in principle be similar to those given off by B. trifoliolata‘s usual plant neighbors. But there is little reason to expect they would have the same relationship to the leaf shape. There could be some other cue or signal that B. trifoliolata is using to decide what kind of leaves to grow, but of the options proposed so far, the visual explanation seems to fit these particular results the best.

Now, I suppose there might be some sort of parable in here somewhere about being careful who you mimic. Only, I’m not even sure copying plastic leaves is detrimental. After all, they are certainly inedible and possibly toxic to whatever might try to eat them. So if there were a situation in which B. trifoliolata was around artificial plants and subject to consumption, prospective snackers might just leave both of them alone. Thus whatever moral might be here could just as easily be to imitate well or flexibly instead of discriminately.

I prefer to simply sit with how profoundly different an experience of being plants must have. Somehow, the thought that they might have some form of vision makes them seem both more and less relatable. More, because vision would give me something in common where there seems to be so little. Less, because that vision likely is not associated with conscious awareness; the plants may very well be processing information from light without any related concept of seeing. It is difficult to imagine what that might be like, not least of all because it might not be like anything.

And yet, despite that difficulty, I find myself further wondering if God’s experience of being is some superset of the experiences of all living things. Not in some pantheistic sense that the plants are God or part of God or anything like that. Rather, that God has the capacity to sense light the way these plants might as well as the way we do. I don’t know if that’s true, I don’t know how to know whether it is true. Still, it feels like a question worth asking.

Breaking news: The 2024 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine goes to Victor Ambros and Gary Ruvkun for “the discovery of microRNA and its role in post-transcriptional gene regulation.” We knew prior to their work that proteins could influence which genes get made into other proteins in different cells. Ambros and Ruykun found that small molecules of RNA could also influence gene expression. This is a topic near and dear to Science Corner contributor Julie Reynolds; perhaps she will be willing to share her perspective on this development in the future.

Andy has worn many hats in his life. He knows this is a dreadfully clichéd notion, but since it is also literally true he uses it anyway. Among his current metaphorical hats: husband of one wife, father of two teenagers, reader of science fiction and science fact, enthusiast of contemporary symphonic music, and chief science officer. Previous metaphorical hats include: comp bio postdoc, molecular biology grad student, InterVarsity chapter president (that one came with a literal hat), music store clerk, house painter, and mosquito trapper. Among his more unique literal hats: British bobby, captain’s hats (of varying levels of authenticity) of several specific vessels, a deerstalker from 221B Baker St, and a railroad engineer’s cap. His monthly Science in Review is drawn from his weekly Science Corner posts — Wednesdays, 8am (Eastern) on the Emerging Scholars Network Blog. His book Faith across the Multiverse is available from Hendrickson.

Leave a Reply