When I was seventeen, a family friend warned me to be careful with my plans to study English literature at university: “A lot of people lose their faith.” It wasn’t that the church environment I grew up in was anti-intellectual or suspicious of higher education per se. Many members were well educated professionals; there were one or two academics, though their work life tended to be regarded with benign bemusement. But this friend’s comment communicated the sense that plunging too deeply into the secular humanities was a risky move. Theology was of course necessary for church leaders, but the -ologies and -isms that dealt with human culture were a trickier line to walk.

Two postdocs into a precarious academic career, I’ve been walking that line one way or another for the last dozen years. I don’t think my friend was wrong exactly: the immersion in critical thinking required during apprenticeship into the humanities can indeed bring into question many received certainties of cradle Christians, and in some cases that tips people over the edge of a faltering faith. But it’s been my experience that the study of literature, and of the cultures it distils and constructs, has been one tool used by God to build and refine my faith, not a high road to its collapse.

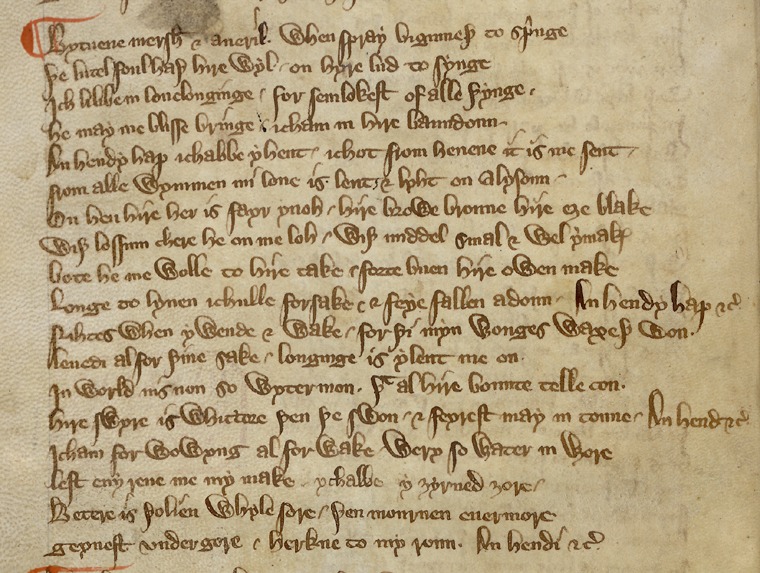

I’m teaching medieval English literature at the moment and recently guided several discussions with students on Middle English lyrics. One of the most intriguing examples we looked at was this little verse found in a manuscript now held at New College, Oxford:

Louerd, thu clepedest me

And ich nagt ne answarede thee

Bute wordes scloe and sclepie:

Thole yet! Thole a litel!

Bute yet and yet was endelis

And thole a litel a long wey is.[1]Lord, you called me

And I answered you with nothing

But sleepy, slow words:

“Be patient yet! Be patient a while!”

But ‘yet’ – and ‘yet’ – was endless

And ‘wait a while’ is a long, long way.[2]

If it sounds familiar then you’re probably a historical theologian with an excellent memory: it’s a translation of a passage from Augustine’s Confessions, the late antique Latin work of spiritual autobiography that was (and continues to be) so influential in Christian culture. The Middle English poet closely renders the dramatised, ironised conversation of the delaying convert with Christ, but makes a couple of adjustments.

Where in the original the verb of the speech in line 4 has the meaning ‘allow’ or ‘let (me) be’, conveying Augustine’s dilettante reluctance to take God’s call seriously, ‘thole’ in the Middle English combines the meanings of waiting and suffering which also coalesce in ‘patience’, communicating the idea of Christ longing for the belated prodigal. And in the last line, the tense shifts from Augustine’s storytelling past, to the present: the Middle English speaker’s experience continues, and at the same time becomes a warning directly to you, the reader, that delay may take you farther away than you think.

I hadn’t come across this lyric before preparing to teach this term, but it threw me straight back to the way my undergraduate study of literature opened up sudden, unexpected new vistas in my understanding of my faith and particularly of Christians in the past. I had operated mostly under the common, largely unspoken evangelical assumption that after the early church, there wasn’t much to think about or learn from in historical Christian life and thought until the Reformation dawned. But the lived theology, devotional intensity, and Christ-centred creativity of medieval religious literature up-ended that model once and for all.

Writers like Julian of Norwich, the visionary poet of suffering and theodicy; the anonymous author of ‘The Cloud of Unknowing’, walking a tightrope of paradox in an attempt to know God truly; and the vast array of totally unknown men and women like the writer of ‘Louerd thu clepedest me’, all orbiting around Christ and his death and what it meant in this world, now – all these showed me that I had brothers and sisters throughout history, and I needed to take them seriously. But it was more than knowing about these people: it was encountering them through their words.

This shift in my thinking wasn’t brought about by reading a work of church history, or engaging with theological discussion about the nature of the church. Instead, it emerged through my being invited and equipped to approach the written word through the lens of the humanities, and particularly literary study – encountering medieval literary works not first as devotional or theological material, but as finely crafted and fascinating products of their era. They were part of a heritage of English literature that still spoke to me and to my classmates.

What exactly do I mean by that word ‘spoke’? In an important way, I think, reading as a literary critic and historian creates communion: an encounter with the other which is like prayer – not exactly the same, but drawing on something similar about reality, language, and the human person. (This is something I theorised in more detail in my doctoral thesis and in a recent article.) The ways of reading and thinking in which I was trained can actually aid my participation in the Church universal, in God’s relational world: rather than undermining my faith, they have the capacity to strengthen it, teaching me about prayer as a form of attention, which in a very real way is on a continuum with critical reading.

The lesson of prayer and reading as forms of attention, and thus as encounter with the other, is one I am still learning in all areas of my life. There have certainly been challenges as I have explored different facets of the literary humanities as a Christian. But the overall story doesn’t bear out my friend’s fear. Instead, the work I’ve been privileged to do has opened up more of Christ and his Church to me, and pushed me to delve deeper into them than I would have done otherwise.

[1] Middle English Lyrics, eds. Maxwell S. Luria and Richard L. Hoffman (Norton, 1973), p. 92. The manuscript is Oxford, New College MS 88.

[2] Translation my own and a little free in the second half!

Alicia Smith is a postdoctoral researcher in medieval studies, currently the Parker Library early-career research fellow at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge. She works on medieval recluses, harlot saints, manuscripts and more. She tries to spend as much of her spare time as possible looking at trees, reading science fiction, and cooking for friends. She writes for the Faith in Scholarship (https://thinkfaith.net/fisch/) initiative of the Thinking Faith Network

Leave a Reply